Bone tumors - Differential diagnosis

Henk Jan van der Woude and Robin Smithuis

Radiology department of the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam and the Alrijne hospital in Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

In this article we will discuss a systematic approach to the differential diagnosis of bone tumors and tumor-like lesions.

The differential diagnosis mostly depends on the review of the conventional radiographs and the age of the patient.

Abbreviations used:

- ABC = Aneurysmal bone cyst

- CMF = Chondromyxoid fibroma

- EG = Eosinophilic Granuloma

- GCT = Giant cell tumour

- FD = Fibrous dysplasia

- HPT = Hyperparathyroidism with Brown tumor

- NOF = Non Ossifying Fibroma

- SBC = Simple Bone Cyst

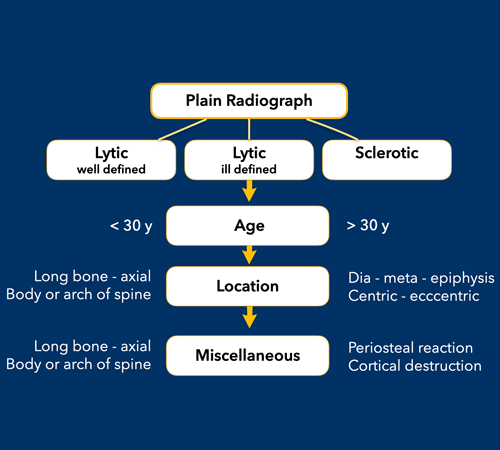

Systematic Approach

The most important determinators in the analysis of a potential bone tumor are:

-

The morphology of the bone lesion on a plain radiograph

- Well-defined osteolytic

- ill-defined osteolytic

- Sclerotic

- The age of the patient

It is important to realize that the plain radiograph is the most useful examination for differentiating these lesions.

CT and MRI are only helpful in selected cases.

Here are links to other articles about bone tumors:

Approach

Most bone tumors are osteolytic.

The most reliable indicator in determining whether these lesions are benign or malignant is the zone of transition between the lesion and the adjacent normal bone (1).

Once we have decided whether a bone lesion is sclerotic or osteolytic and whether it has a well-defined or ill-defined margins, the next question should be: how old is the patient?

Age is the most important clinical clue.

Finally other clues need to be considered, such as a lesion's localization within the skeleton and within the bone, any periosteal reaction, cortical destruction, matrix calcifications, etc.

Age

Age is the most important clinical clue in differentiating possible bone tumors.

There are many ways of splitting age groups, as can be seen in the table, where the morphology of a bone lesion is combined with the age of the patient.

Some prefer to divide patients into two age groups: 30 years.

Most primary bone tumors are seen in patients In patients > 30 years we must always include metastases and myeloma in the differential diagnosis.

Notice the following:

- Infections, a common tumor mimicker, are seen in any age group.

- Infection may be well-defined or ill-defined osteolytic, and even sclerotic.

- Eosinophilic Granuloma and infections should be mentioned in the differential diagnosis of almost any bone lesion in patients < 20 years.

- Many sclerotic lesions in patients > 20 years are healed, previously osteolytic lesions which have ossified, such as: NOF, EG, SBC, ABC and chondroblastoma.

Zone of transition

In order to classify osteolytic lesions as well-defined or ill-defined, we need to look at the zone of transition between the lesion and the adjacent normal bone.

The zone of transition is the most reliable indicator in determining whether an osteolytic lesion is benign or malignant (1).

The zone of transition only applies to osteolytic lesions since sclerotic lesions usually have a narrow transition zone.

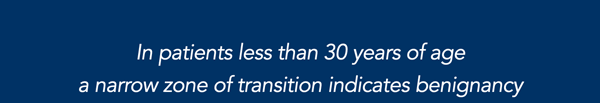

Small zone of transition

A small zone of transition results in a sharp, well-defined border and is a sign of slow growth.

A sclerotic border especially indicates poor biological activity.

In patients

In patients > 30 years, and particularly > 40 years, despite benign radiographic features, a metastasis or plasmacytoma also have to be considered

On the left three bone lesions with a narrow zone of transition.

Based on the morphology and the age of the patients, these lesions are benign.

Notice that in all three patients, the growth plates have not yet closed.

Images

- Non-ossifying fibroma

- Solitary bone cyst

- Aneurysmal bone cyst

Metastases and multiple myeloma

In patients > 40 years metastases and multiple myeloma are the most common bone tumors.

Metastases under the age of 40 are extremely rare, unless a patient is known to have a primary malignancy.

Metastases could be included in the differential diagnosis if a younger patient is known to have a malignancy, such as neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma or retinoblastoma.

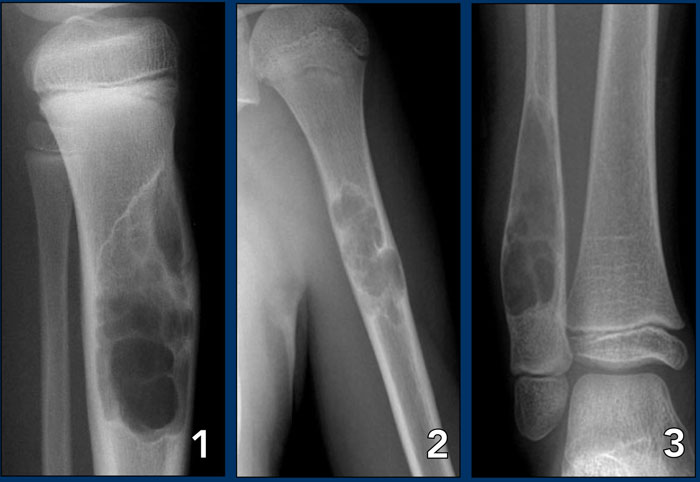

Wide zone of transition

An ill-defined border with a broad zone of transition is a sign of aggressive growth (1).

It is a feature of malignant bone tumors.

There are two tumor-like lesions which may mimic a malignancy and have to be included in the differential diagnosis.

These are infections and eosinophilic granuloma.

Both of these entities may have an aggressive growth pattern.

Images

- Osteosarcoma

- Osteomyelitis

- Eosinophilic granuloma

Infections and eosinophilic granuloma

Infections and eosinophilic granuloma are exceptional because they are benign lesions which can mimick a malignant bone tumor due to their aggressive biologic behavior.

These lesions may have ill-defined margins, but cortical destruction and an aggressive type of periosteal reaction may also be seen.

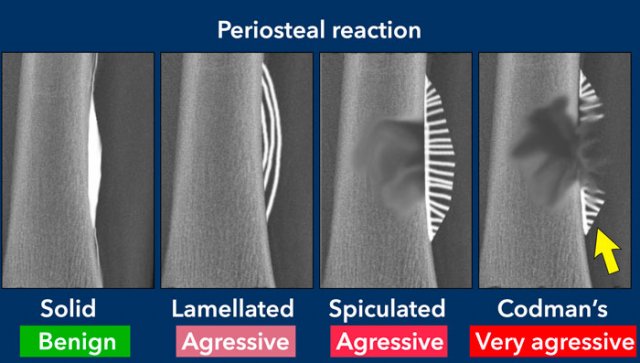

Periosteal reaction

A periosteal reaction is a non-specific reaction and will occur whenever the periosteum is irritated by a malignant tumor, benign tumor, infection or trauma.

There are two patterns of periosteal reaction: a benign and an aggressive type.

The benign type is seen in benign lesions such as benign tumors and following trauma.

An aggressive type is seen in malignant tumors, but also in benign lesions with aggressive behavior, such as infections and eosinophilic granuloma.

Fibrous dysplasia, Enchondroma, NOF and SBC are common bone lesions.

They will not present with a periosteal reaction unless there is a fracture.

If no fracture is present, these bone tumors can be excluded.

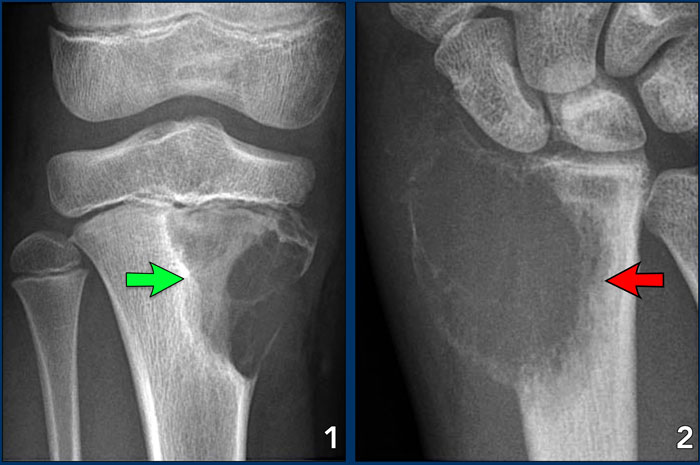

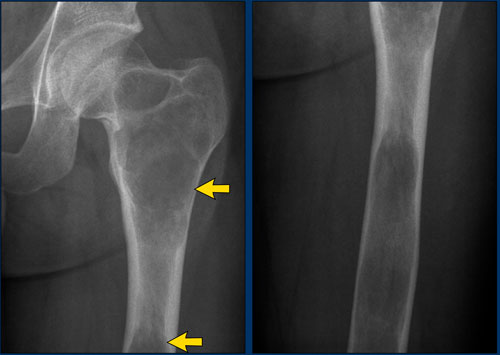

Benign periosteal reaction

Detecting a benign periosteal reaction may be very helpful, since malignant lesions never cause a benign periosteal reaction.

A benign type of periosteal reaction is a thick, wavy and uniform callus formation resulting from chronic irritation.

In the case of benign, slowly growing lesions, the periosteum has time to lay down thick new bone and remodel it into a more normal-appearing cortex.

Image

Benign periosteal reaction in an osteoid osteoma.

Large arrow indicates solid periosteal reaction.

Small arrow indicates nidus.

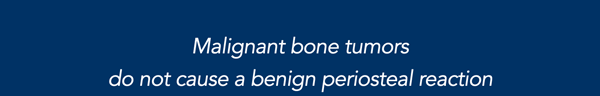

Aggressive periosteal reaction

This type of periostitis is multilayered, lamellated or demonstrates bone formation perpendicular to the cortical bone.

It may be spiculated and interrupted - sometimes there is a Codman's triangle.

A Codman's triangle refers to an elevation of the periosteum away from the cortex, forming an angle where the elevated periosteum and bone come together.

In aggressive periostitis the periosteum does not have time to consolidate.

Aggressive periosteal reaction (2)

- Osteosarcoma with interrupted periosteal rection and Codman's triangle proximally (red arrow).

There is periosteal bone formation perpendicular to the cortical bone and extensive bony matrix formation by the tumor itself. - Ewing sarcoma with lamellated and focally interrupted periosteal reaction. (white arrows)

- Infection with a multilayered periosteal reaction.

Notice that the periostitis is aggressive, but not as aggressive as in the other two cases.

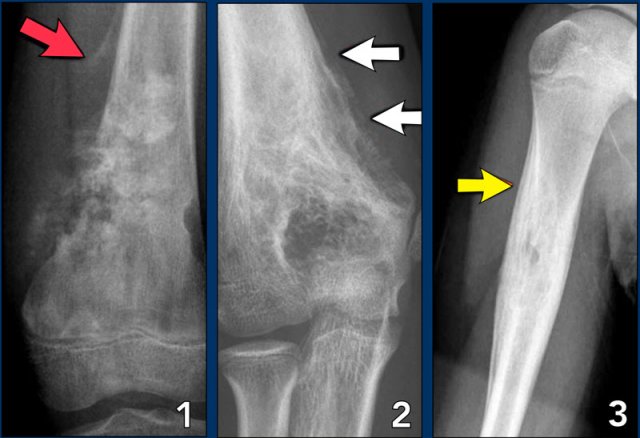

Cortical destruction

Cortical destruction is a common finding, and not very useful in distinguishing between malignant and benign lesions.

Complete destruction may be seen in high-grade malignant lesions, but also in locally aggressive benign lesions like EG and osteomyelitis.

More uniform cortical bone destruction can be found in benign and low-grade malignant lesions.

Endosteal scalloping of the cortical bone can be seen in benign lesions like Fybrous dysplasia and low-grade chondrosarcoma.

Images

- Osteosarcoma

Irregular cortical destruction - Ewing's sarcoma

Cortical destruction (green arrow) and aggressive periosteal reaction (arrow heads).

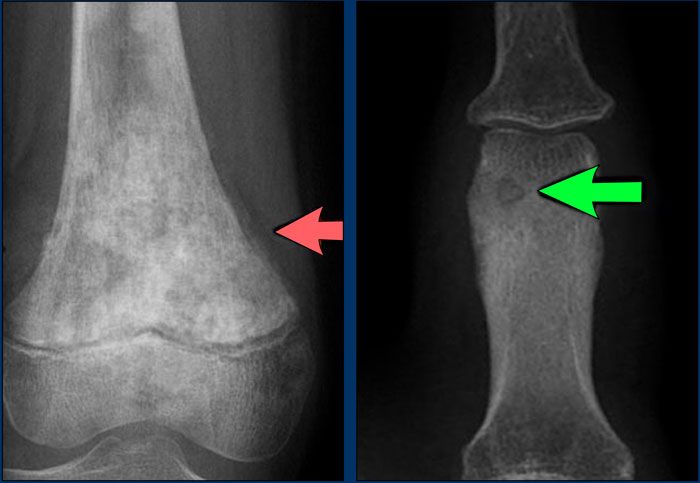

Ballooning

Ballooning is a special type of cortical destruction.

In ballooning the destruction of endosteal cortical bone and the addition of new bone on the outside occur at the same rate, resulting in expansion.

This 'neocortex' can be smooth and uninterrupted, but may also be focally interrupted in more aggressive lesions like GCT.

Images

- Chondromyxoid fibroma

A benign, well-defined, expansile lesion with regular destruction of cortical bone and a peripheral layer of new bone. - Giant cell tumor

A locally aggressive lesion with cortical destruction, expansion and a thin, interrupted peripheral layer of new bone.

Notice the wide zone of transition towards the marrow cavity, which is a sign of aggressive behavior (red arrow).

Ewing's sarcoma with permeative growth through the haversian channels accompanied by a large soft tissue mass

Ewing's sarcoma with permeative growth through the haversian channels accompanied by a large soft tissue mass

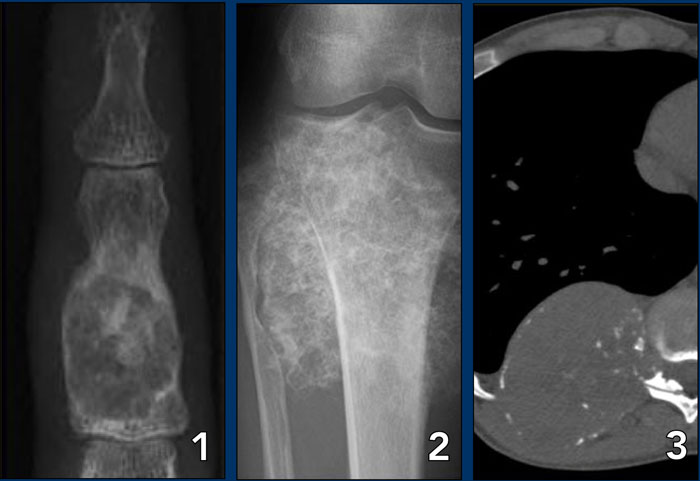

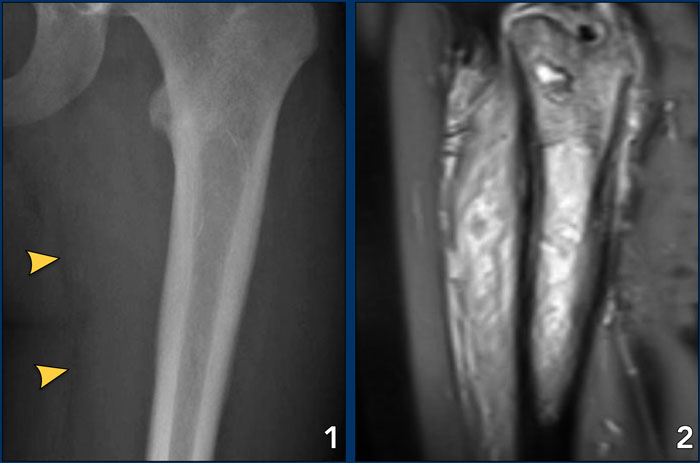

Cortical destruction (3)

In the group of malignant small round cell tumors which include Ewing's sarcoma, bone lymphoma and small cell osteosarcoma, the cortex may appear almost normal radiographically, while there is permeative growth throughout the Haversian channels.

These tumors may be accompanied by a large soft tissue mass while there is almost no visible bone destruction.

Images

- Ewing's sarcoma

The radiograph does not shown any signs of cortical destruction. - MRI shows large tumor within the bone and permeative growth through the Haversian channels accompanied by a large soft tissue mass, which is barely visible on the X-ray.

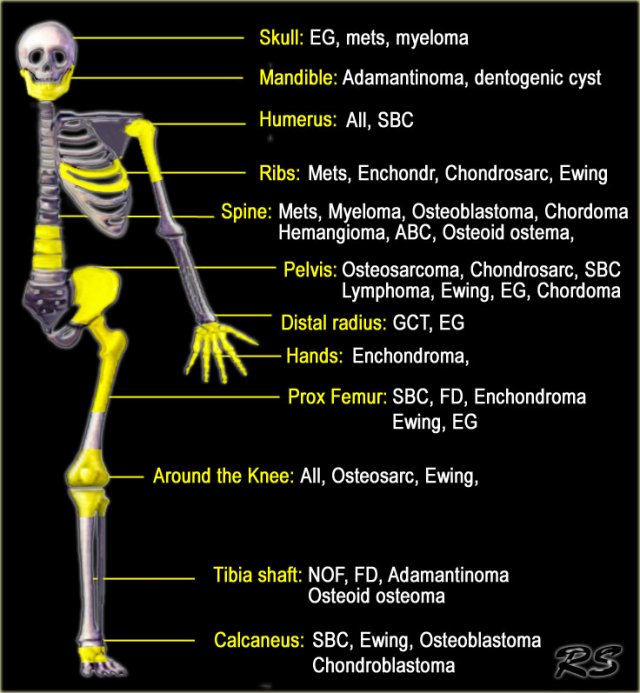

Location within the skeleton

The location of a bone lesion within the skeleton can be a clue in the differential diagnosis.

The illustration on the left shows the preferred locations of the most common bone tumors.

In some locations, such as in the humerus or around the knee, almost all bone tumors may be found.

Top five location of bone tumors in alphabethic order:

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst - tibia, femur, fibula, spine, humerus

Adamantinoma - tibia shaft, mandible

Chondroblastoma - femur, humerus, tibia, tarsal bone (calc), patella

Chondromyxoid fibroma - tibia, femur, tarsal bone, phalanx foot, fibula

Chondrosarcoma - femur, rib, iliac bone, humerus, tibia

Chordoma - sacrococcygeal, spheno-occipital, cervical, lumbar, thoracic

Eosinophilic Granuloma - femur, skull, iliac bone, rib, vertebra

Enchondroma - phalanges of hands and feet, femur, humerus, metacarpals, rib

Ewing's sarcoma - femur, iliac bone, fibula, rib, tibia

Fibrous dysplasia - femur, tibia, rib, skull, humerus

Giant Cell Tumor - femur, tibia, fibula, humerus, distal radius

Hemangioma - spine, ribs, craniofacial bones, femur, tibia

Lymphoma - femur, tibia, humerus, iliac bone, vertebra

Metastases - vertebrae, ribs, pelvis, femur, humerus

Non Ossifying Fibroma - tibia, femur, fibula, humerus

Osteoid osteoma - femur, tibia, spine, tarsal bone, phalanx

Osteoblastoma - spine, tarsal bone (calc), femur, tibia, humerus

Osteochondroma - femur, humerus, tibia, fibula, pelvis

Osteomyelitis - femur, tibia, humerus, fibula, radius

Osteosarcoma - femur, tibia, humerus, fibula, iliac bone

Solitary Bone Cyst - proximal humerus, proximal femur, calcaneal bone, iliac bone

Location: epiphysis - metaphysis - diaphysis

- Epiphysis

Only a few lesions are located in the epiphysis, so this could be an important finding.

In young patients it is likely to be either a chondroblastoma or an infection.

In patients over 20, a giant cell tumor has to be included in the differential diagnosis.

In older patients a geode, i.e. degenerative subchondral bone cyst must be added to the differential diagnosis.

Look carefully for any signs of arthrosis. - Metaphysis

NOF, SBC, CMF, Osteosarcoma, Chondrosarcoma, Enchondroma and infections. - Diaphysis

Ewing's sarcoma, SBC, ABC, Enchondroma, Fibrous dysplasia and Osteoblastoma.

Differentiating between a diaphyseal and a metaphyseal location is not always possible.

Many lesions can be located in both or move from the metaphysis to the diaphysis during growth.

Large lesions tend to expand into both areas.

Location: centric - eccentric - juxtacortical

- Centric in long bone

SBC, eosinophilic granuloma, fibrous dysplasia, ABC and enchondroma are lesions that are located centrally within long bones. - Eccentric in long bone

Osteosarcoma, NOF, chondroblastoma, chondromyxoid fibroma, GCT and osteoblastoma are located eccentrically in long bones. - Cortical

Osteoid osteoma is located within the cortex and needs to be differentiated from osteomyelitis. - Juxtacortical

Osteochondroma. The cortex must extend into the stalk of the lesion.

Parosteal osteosarcoma arises from the periosteum.

- SBC: central diaphyseal

- NOF: eccentric metaphyseal

- SBC: central diaphyseal

- Osteoid osteoma: cortical

- Degenerative subchondral cyst: epiphyseal

- ABC: centric diaphyseal

Matrix

Calcifications or mineralization within a bone lesion may be an important clue in the differential diagnosis.

There are two kinds of mineralization:

- Chondroid matrix in cartilaginous tumors like enchondromas and chondrosarcomsa

- Osteoid matrix in osseus tumors like osteoid osteomas and osteosarcomas.

Chondroid matrix

Calcifications in chondroid tumors have many descriptions: rings-and-arcs, popcorn, focal stippled or flocculent.

Images

- Enchondroma, the most commonly encountered lesion of the phalanges.

- Peripheral chondrosarcoma, arising from an osteochondroma (exostosis).

- Chondrosarcoma of the rib.

Osteoid matrix

Mineralization in osteoid tumors can be described as a trabecular ossification pattern in benign bone-forming lesions and as a cloud-like or ill-defined amorphous pattern in osteosarcomas.

Sclerosis can also be reactive, e.g. in Ewing's sarcoma or lymphoma.

- left

Cloud-like bone formation in osteosarcoma.

Notice the aggressive, interrupted periosteal reaction (arrows). - right

Trabecular ossification pattern in osteoid osteoma.

Notice osteolytic nidus (arrow).

Polyostotic or multiple lesions

Most bone tumors are solitary lesions.

If there are multiple or polyostotic lesions, the differential diagnosis must be adjusted.

Polyostotic lesions

NOF, fibrous dysplasia, multifocal osteomyelitis, enchondromas, osteochondoma, leukemia and metastatic Ewing' s sarcoma.

Multiple enchondromas are seen in Morbus Ollier.

Multiple enchondromas and hemangiomas are seen in Maffucci's syndrome.

Polyostotic lesions > 30 years

Common: Metastases, multiple myeloma, multiple enchondromas.

Less common: Fibrous dysplasia, Brown tumors of hyperparathyroidism, bone infarcts.

Mnemonic for multiple oseolytic lesions: FEEMHI:

Fibrous dysplasia, enchondromas, EG, Mets and myeloma, Hyperparathyroidism, Infection.

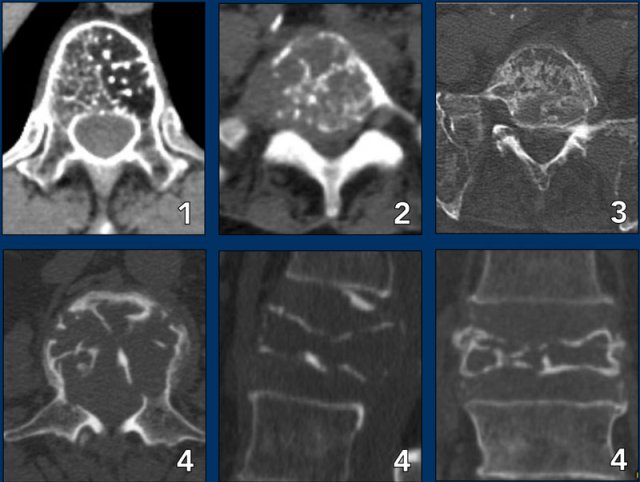

Spine lesions

Here some typical examples of bone tumors in the spine.

- Hemangioma.

- Metastasis.

- Multiple myeloma.

- Plasmocytoma: vertebra plana.

This 'Mini Brain' appearance of plasmacytoma in the spine is sufficiently pathognomonic to obviate biopsy (9).

More examples

- ABC

- Chondrosarcoma

- Metastasis of breast cancer

- Osteoblastoma

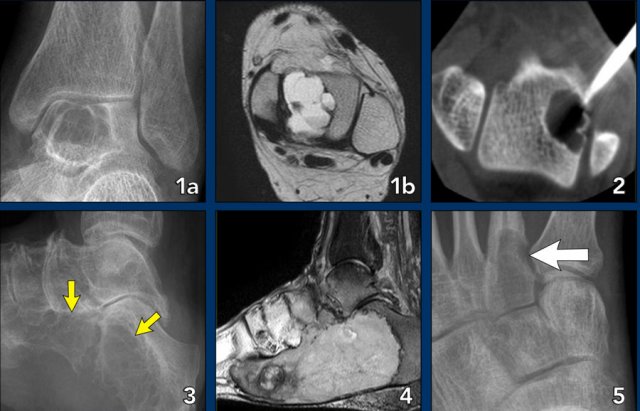

Foot lesions

Here some typical examples of bone tumors in the foot:

- Geode or subchondral cyst in the navicular bone

- Geode or subchondral cyst in the tarsal bone

- Chondroblastoma in the tarsal bone

- X-ray and MRI of a chondroblasoma in the tarsal bone

- Chondroblastoma in the tarsal bone

- Aneurysmal bone cyst in the tarsal bone

- Chondroblastoma in the tarsal bone

- Chondromyxoid fibroma (CMF) in the calcaneus

- Same patient MRI

- CMF in the second metatarsal bone

- Ewing sarcoma in the calcaneus

- Glomus tumor

- Same patient MRI