Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage

Amber Bucker, Henriette Westerlaan, Aryan Mazuri, Maarten Uyttenboogaart and Robin Smithuis

University Medical Center Groningen and Alrijne Hospital in Leiderdorp, the Netherlands

Any type of bleeding inside the skull or brain is a medical emergency.

The most common causes of hemorrhage are trauma, haemorrhagic stroke and subarachnoid haemorrhage due to a ruptured aneurysm.

Complications are increased intracerebral pressure as a result of the hemorrhage itself, surrounding edema or hydrocephalus due to obstruction of CSF.

In this article we will discuss traumatic hemorrhages.

Non-traumatic hemorrhages are discussed here.

Press ctrl+ for larger images and text on a PC or ⌘+ on a Mac.

Most images can be enlarged by clicking on them.

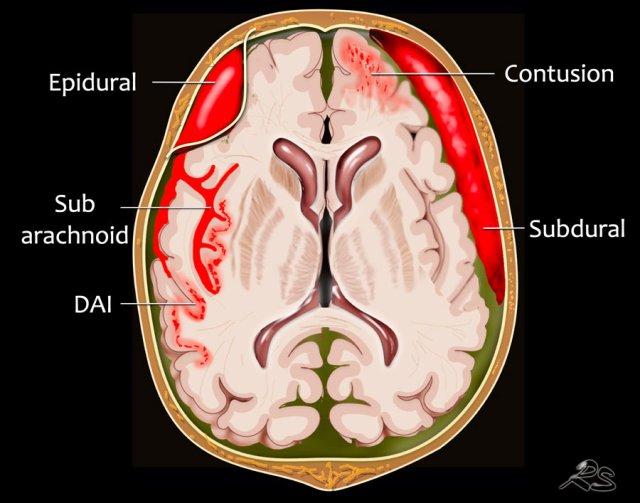

Localization of hemorrhage

Extra-axial hemorrhage - Intracranial extracerebral

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage is acute bleeding under the arachnoid. Most commonly seen in rupture of an aneurysm or as a result of trauma.

- Subdural hematoma is a bleeding between the inner layer of the dura mater and the arachnoid mater of the meninges. It usually results from traumatic tearing of the bridging veins that cross the subdural space in patients with anticoagulantia therapy.

- Epidural hematoma is bleeding in the virtual space between the dura mater and the skull. Seen in fracture of the temporal bone with rupture of the middle meningeal artery.

Intra-axial hemorrhage - intracerebral

- Cerebral hemorrhagic contusion small post-traumatic hemorrhages located near the skull in the area of the coupe and contre-coup, most commonly frontobasal and anterior in the temporal lobes. Sometimes in combination with a subdural hematoma or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Diffuse axonal injury (DAI). Diffuse injury at the level of the gray-white matter junction seen in high velocity injuries. CT has low sensitivity. Better seen on MRI.

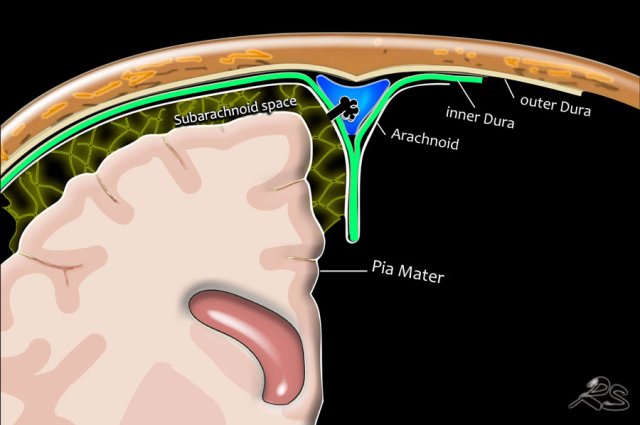

Anatomy of the meninges

Meninges are the three membranes that envelop the brain and spinal cord: the dura mater, the arachnoid mater, and the pia mater.

Cerebrospinal fluid is located in the subarachnoid space between the arachnoid mater and the pia mater.

Dura mater is the outermost meningeal layer that covers the brain and spinal cord.

It consists of two layers: the inner meningeal layer and the outer periosteal layer.

Arachnoid is a layer with delicate fibres which extend down through the subarachnoid space and attach to the pia mater.

Arachnoid granulations - also called Pacchionian granulations - are small protrusions of the arachnoid mater through the outer membrane of the dura mater into the dural venous sinuses of the brain, and allow cerebrospinal fluid to exit the subarachnoid space and enter the blood stream.

Pia mater is the innermost layer covering the brain.

The pia mater allows blood vessels to pass through and nourish the brain.

The arachnoid and pia mater together are sometimes called the leptomeninges.

Traumatic hemorrhage

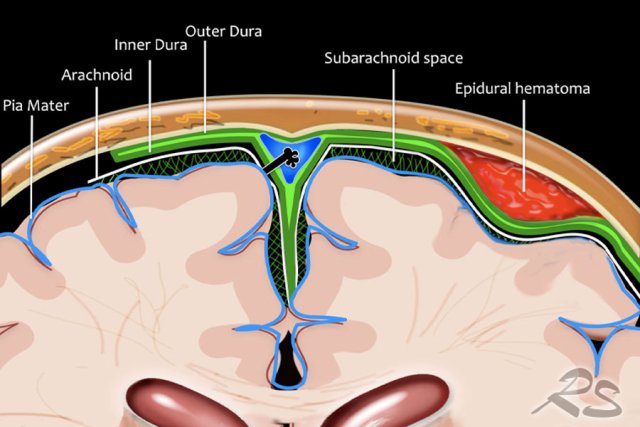

Epidural hematoma

An epidural hematoma is a bleeding that occurs between the dura and the skull.

It is mostly seen in children who have a head injury with fracture of the temporal bone resulting in tearing of the middle meningeal artery.

In theory an epidural hematoma can cross the midline because it is located between the dura and the skull.

However since the dura is tightly adherent to the adjacent skull near suture lines, an epidural hematoma usually does not cross suture lines.

A 11 year-old boy fell off his bike probably due to an epileptic convulsion.

He hit the curb with his head.

His level of consciousness was lowered and his EMV score was 2-4-3.

He presented with bradycardia, hypertension, abnormal posturing and a non-reactive dilated right pupil, which are all signs of brain herniation and raised intracranial pressure.

CT findings

- Lentiform temporoparietal hemorrhage is shown

- The hemorrhage is limited in its extent by the cranial sutures.

- Associated skull fracture

- Swirl sign indicating extravasation of blood into the hematoma. It represents unclotted fresh blood, which is of lower attenuation than the clotted blood which surrounds it.

- Horizontal subfalcine and uncal herniation.

A craniotomy was performed subsequently and the torn middle meningeal artery was coagulated.

Clinical outcome was good.

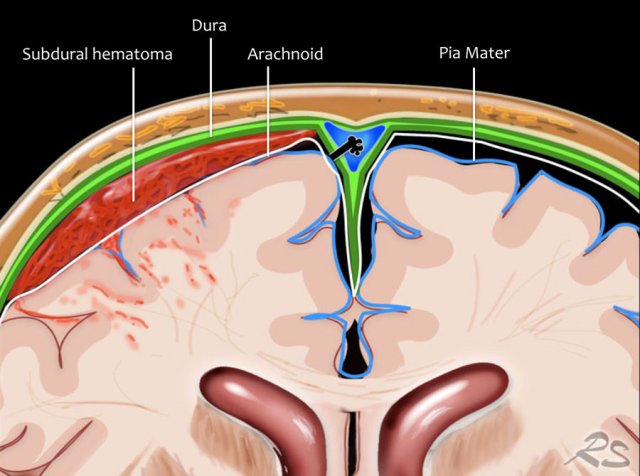

Subdural hematoma

A subdural hematoma is a collection of blood between the inner layer of the dura and the arachnoid.

It cannot cross the midline, but can be located near dural folds like the falx or the tentorium.

It usually results from rupture of the cortical bridging veins.

It usually occurs in head trauma and especially in patients who are treated with antcoagulantia.

It is most common in elderly and alcoholics with atrophy.

In brain atrophy the venous subdural structures are less well “packed” against the skull, which give them more space to move and possibility to torn.

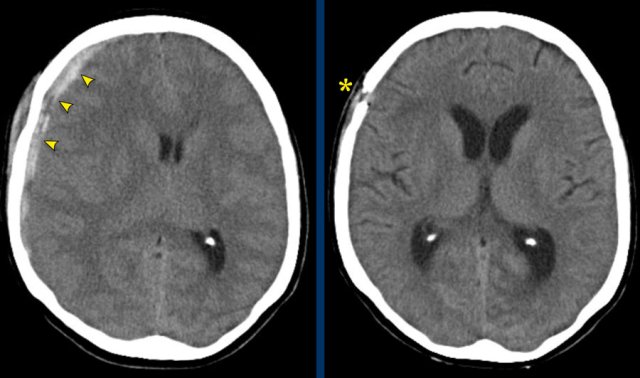

This patient has an acute subdural hematoma.

There is midline shift (left image).

The patient was operated and the hematoma was evacuated (right image).

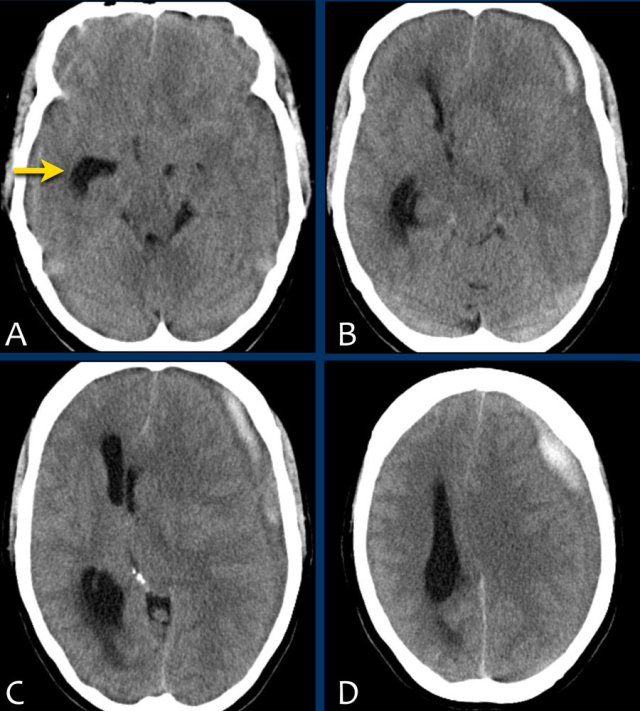

The images show a subdural hematoma.

Notice that the hematoma has both hyperdense and isodense areas.

This can be seen in hyperacute bleeding, but can also be seen in rebleeding.

There is displacement of midline structures with obstruction of CSF flow resulting in dilatation of the temporal horn of the right lateral ventricle (arrow).

An acute subdural hematoma is hyperdens (clotted blood), a subacute hematoma is isodens and a chronic subdural hematoma appears hypodens to brain parenchyma (isodens to CSF).

Sign of active bleeding

In the acute setting, a subdural hematoma can appear heterogenous, because of the mixed components of the hemorrhage: fresh in flow of non clotted blood (hypodens) and clotted blood (hyperdens).

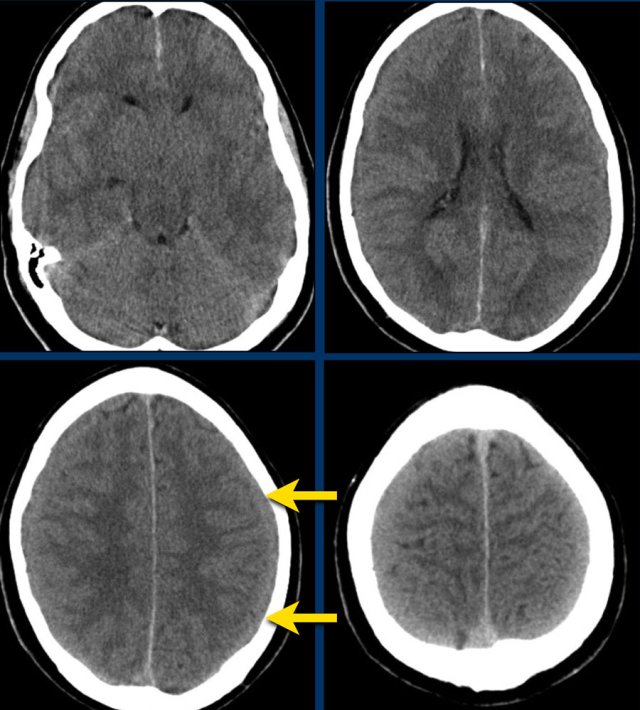

Isodense subdural hematoma

As a subdural hematoma ages, the density of the hematoma will decrease and may be the same as the density of the brain, which make it difficult to detect the hematoma.

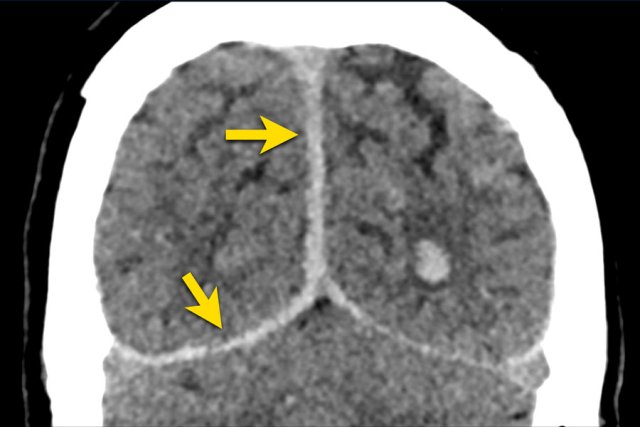

Here a case of an isodense subdural hematoma which is very hard to detect (arrows).

Notice that on a higher level there is a bilateral subdural hematoma.

In rare cases an acute subdural hematoma may be isodense to the brain.

This is seen in patients with severe anemia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or if the hematoma is diluted with cerebrospinal fluid (ref).

When a chronic subdural hematoma (> 21 days) becomes hypodens to parenchyma and isodens to CSF, it may mimick a hygroma.

A hygroma is the result of a traumatic torn in the arachnoid layer which causes CSF to leak to the subdural space,.

A subdural hematoma can spread along the falx and tentorium as seen in this case.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage

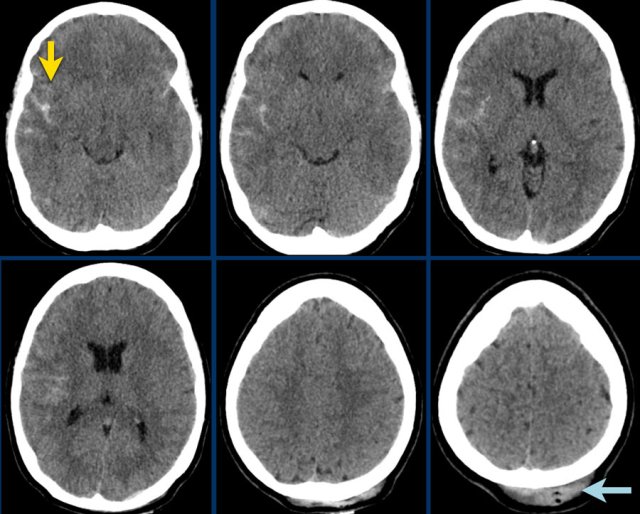

The images show hyperdense blood in the subarachnoid space of the Sylvian fissure (yellow arrow).

Notice the subgaleal hemorrhage in the right occipital region (blue arrow).

This is a coupe contrecoupe type of injury.

This is another coupe contrecoupe type of injury with contusional hemorrhages and a subdural hematoma in the left frontal lobe near the skull base (red arrow).

There is a subarachnoid hemorrhage on the right with a fracture of the parietal bone (yellow arrow).

Diffuse Axonal Injury

High-impact trauma with acceleration-deceleration forces, especially rotational acceleration, can lead to stretching and deformation of the brain tissue, resulting in DAI.

CT has a low sensitivity for detecting DAI.

In closed traumatic brain injury with no traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage or intraventricular hemorrhage DAI is unlikely.

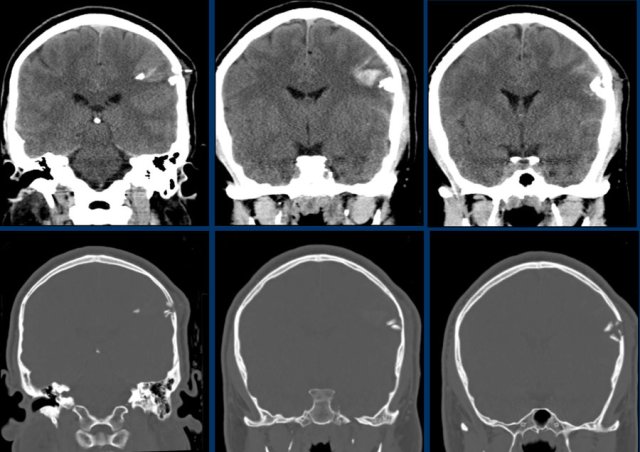

A 46 year-old man had a high energy trauma with his motorcycle.

The initial EMV score was 2-5-3 and his pupils were non-reactive and dilated.

CT findings

- Petechial hemorrhages in both frontal lobes.

- Bilateral Le Fort II fractures.

Continue with the MRI images...

MRI was requested because of persisting cognitive deficits.

MRI findings

- Extensive (stage 3) diffuse axonal injury (DAI)

- Involvement of the subcortical areas, the corpus callosum, the right thalamus and putamen, the brain stem, the cerebellar peduncles and the right cerebellar hemisphere.

- Mild global atrophy.

In closed traumatic brain injury with no traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage or intraventricular hemorrhage a DAI is unlikely.

DAI can be diagnosed accurately conventional MRI, including T2*GRE or SWI.

The presence of DAI on MRI in patients with traumatic brain injury results in a higher chance of unfavourable functional outcome.

Three stages can be distinguished on MRI:

- Visible lesions in the lobar white matter

- Lesions in the corpus callosum

- Lesions in the brainstem.

With MRI grading, the odds ratio for unfavourable functional outcome increases threefold with every grade.

Lesions in the corpus callosum in particular are associated with an unfavourable functional outcome.

This patient has an intracerebral hemorrhage as a result of a stabwound.

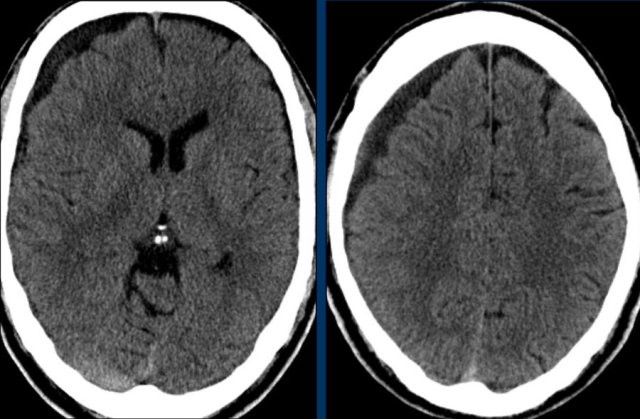

Duret hemorrhage

A 54-year-old man, who was treated with anticoagulants after aortic valve replacement, developed severe headache after being hit by a ball.

The following day his condition worsened with loss of consciousness, respiratory distress and a non-reactive dilated left pupil.

The initial CT of his head showed an acute subdural hemorrhage along the left convexity with subfalcine and uncal herniation. The hemorrhage was evacuated surgically.

Postoperatively the CT showed an acute bleeding within the brainstem, which had a lethal outcome.

This brain stem hemorrhage is called a Duret hemorrhage.

They are small linear areas of bleeding in the midbrain and upper pons of the brainstem caused by a traumatic downward displacement of the brainstem with parahippocampal gyrus herniation through the tentorial hiatus.