Pancreatic Cancer - CT staging 2.0

Assessment of Resectability

Frank Wessels, Otto van Delden and Robin Smithuis

From the Radiology Department of the University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Amsterdam University Medical Centre and the Alrijne hospital in Leiderdorp

Publicationdate

This is the second version of the role of CT in staging pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth largest cause of cancer death in the United States and Europe with over 100,000 deaths per year in Europe alone.

The overall 5-year survival ranges from 2–7 % and has hardly improved over the last two decades.

Approximately 15 % of all patients have presumed resectable disease at diagnosis and of those, only a subgroup has a resectable tumor at surgical exploration.

In this article we will focus on the criteria for resectability versus irresectability and we will provide a checklist that will help you to make a structured report for staging pancreatic cancer and determining resectability.

At the end of the article there will be videos by Frank Wessels on how to stage pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Complete resection of the tumor is the only curative treatment, but pancreatic cancer is seldom detected at an early stage, as 40% of patients present with distant metastases and 40% present with locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC), which is unresectable.

When there are no distant metastases, the resectability mainly depends on the local status determined by:

- Size of the tumor

- Involvement of critical vascular structures as defined by the NCCN or DPCG criteria

- Invasion of nearby structures like transverse mesocolon, root of the mesentery and perineural invasion

- Lymph node involvement locoregional or extraregional

These subjects will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter on staging.

Based on the imaging findings the tumor can be categorized as resectable, borderline resectable or unresectable.

Staging

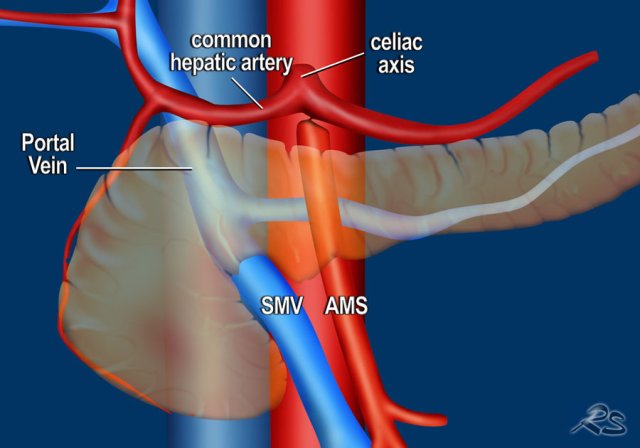

Assessment of vascular involvement

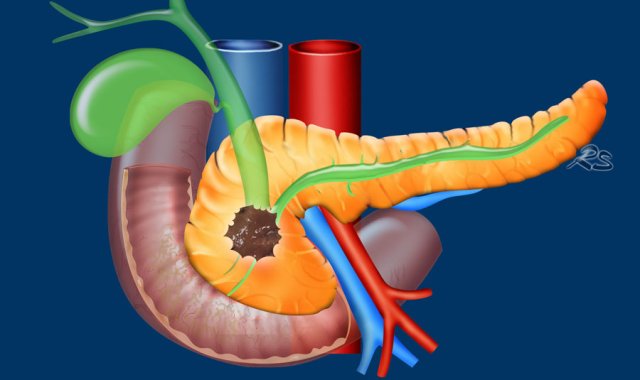

Involvement of critical vascular structures is the most important factor, which determines the resectability of a pancreatic adenocarcinoma (figure).

At the same time it is an important predictor of survival.

The most commonly used resectability criteria for vascular involvement are the criteria of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).

These criteria however are quite complex and that is why several other criteria exist.

For instance in the Netherlands we use the criteria of the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group (DPCG).

We will first discuss the DPCG criteria followed by the NCCN criteria.

Whatever criteria you use, you need to realize that assessment of resectability can be subjective and varies between institutions, especially in the case of portovenous reconstructions.

DPCG resectability criteria

The criteria of the Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group for vascular compromise are relatively simple compared to the NCCN criteria and that is why we present these criteria first (table).

The resectability is also determined by the presence of distant metastases and the lymph node status in which extraregional lymph nodes are regarded as distant metastases.

Important additional findings of interest to the surgeon, that are easily overlooked are:

- Perineural invasion

- Invasion of the root of the mesentery

- Invasion of the mesocolon

These findings will be discussed in the next chapter.

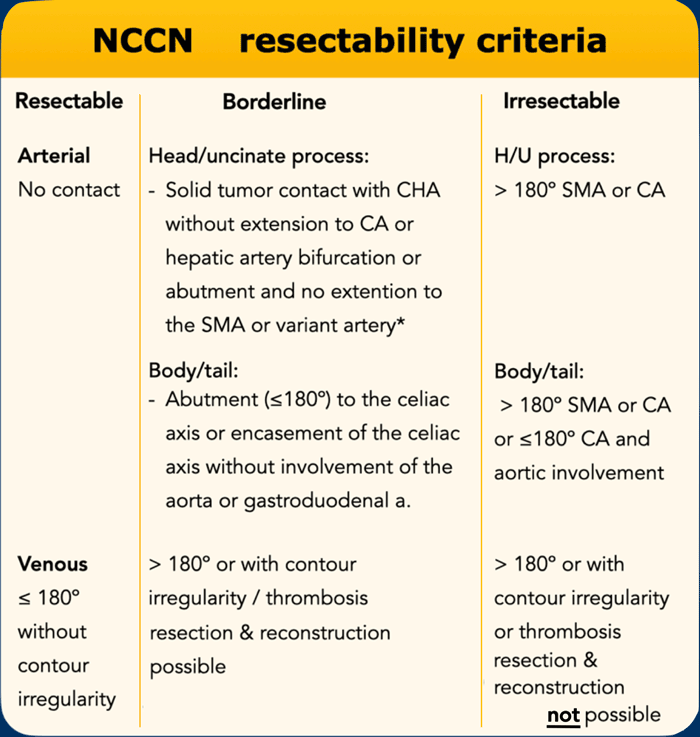

NCCN resectability criteria

Locally irresectable is synonym to locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC).

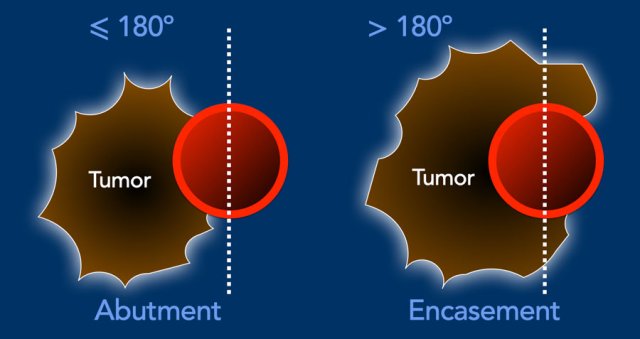

Assessing the degree of circumferential vascular involvement is done in 90 degree steps.

Less than 180 degrees contact is called abutment and more than 180 degrees contact is called encasement.

The probability of vascular invasion is 40% for abutment and 80% for encasement, up to 100% when the tumor is completely surrounding the portal vein or SMV.

In case of venous involvement the length of invasion is also mentioned as this may guide the surgeon in assessing the possibility of reconstruction.

The specificity of CT for detecting vascular invasion ranges from 82-100% and sensitivity from 70-96%.

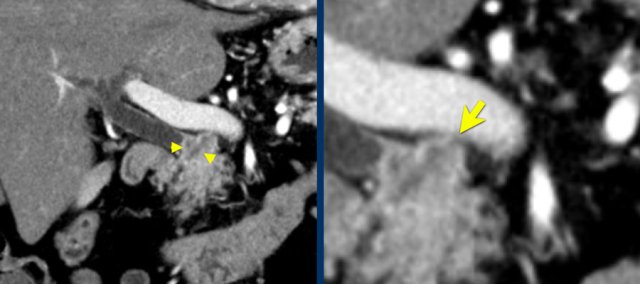

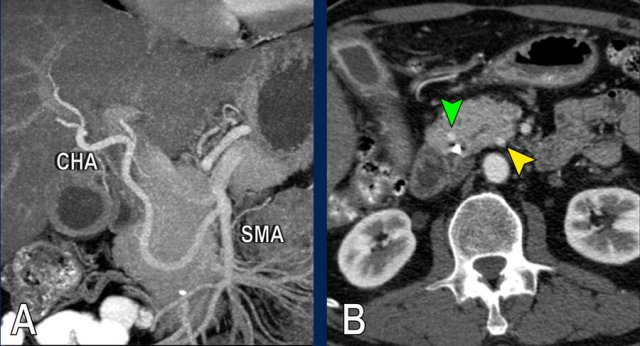

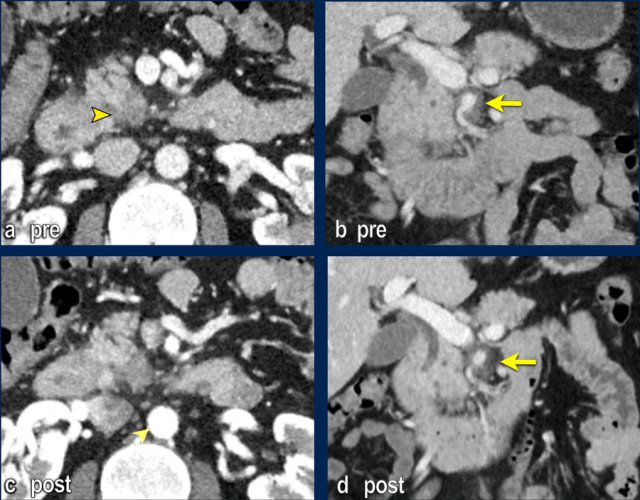

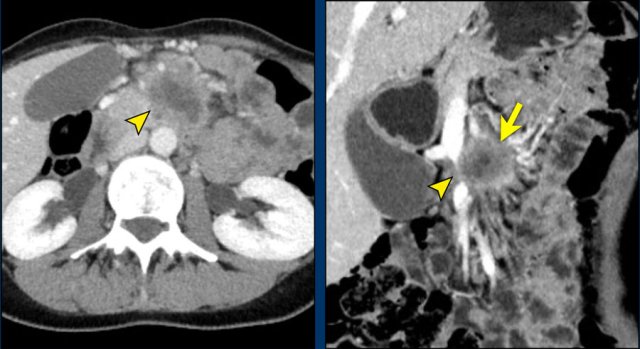

The use of multiplanar reformations improves overall CT performance as seen in this case.

A coronal reformat shows a small tumor in the pancreatic head (arrowheads) with obstruction of the common bile duct.

There seems to be just limited contact with the portal vein (arrow).

Continue with the next images.

A multiplanar reformat perpendicular to the portal vein shows that there is more extensive contact with the portal vein, 90 – 180 degrees (arrow).

Without contour irregularity this is classified as borderline resectable according to the DPCG criteria but resectable according to the NCCN criteria.

Resection without venous reconstruction proved to be R1, meaning presence of microscopic tumor invasion of the resection margin.

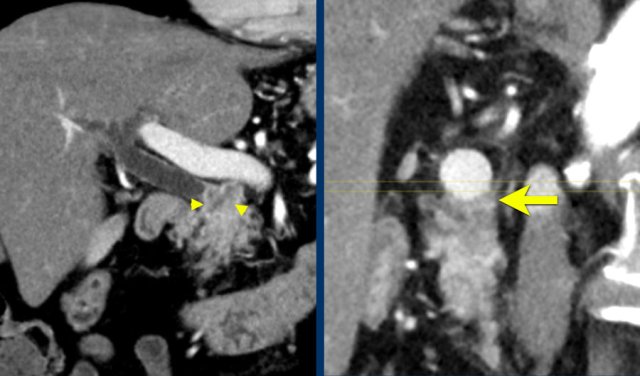

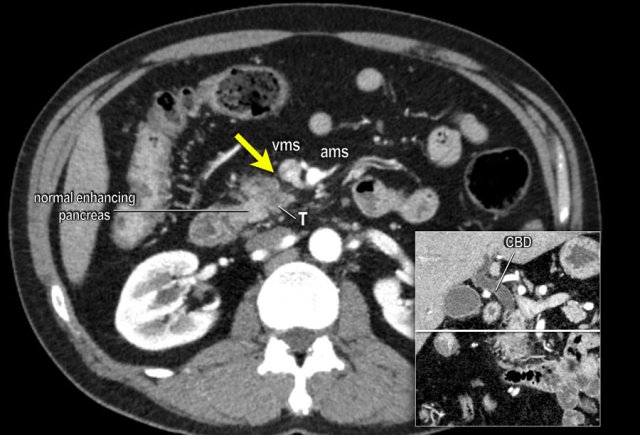

Teardrop sign. A large tumor in the body of the pancreas, 90 – 180 degrees contact with the SMV, but moreover deformation of the SMV into a so called teardrop, highly suspicious for invasion.

Teardrop sign. A large tumor in the body of the pancreas, 90 – 180 degrees contact with the SMV, but moreover deformation of the SMV into a so called teardrop, highly suspicious for invasion.

Morphologic changes that suggest vascular invasion

- Teardrop sign

Refers to a change in shape of the PV or SMV from oval or round to a teardrop. This can be caused by tumor encasement or tethering by adjacent fibrosis. - Vessel contour irregularity

Irregularity of a vessel is suggestive of vascular invasion. Even more so in arteries, since the wall of an artery is thicker than of a vein. - Thrombosis

The presence of thrombus in an artery is suggestive of vascular invasion.

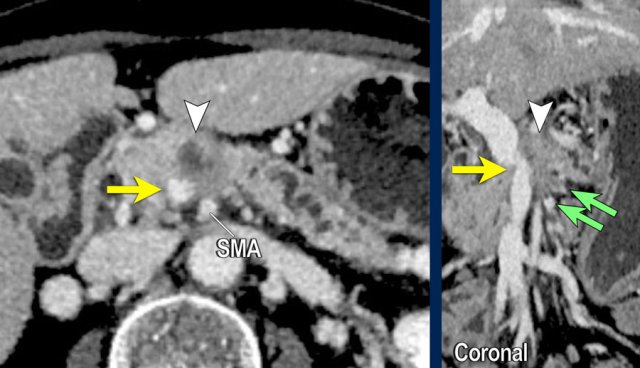

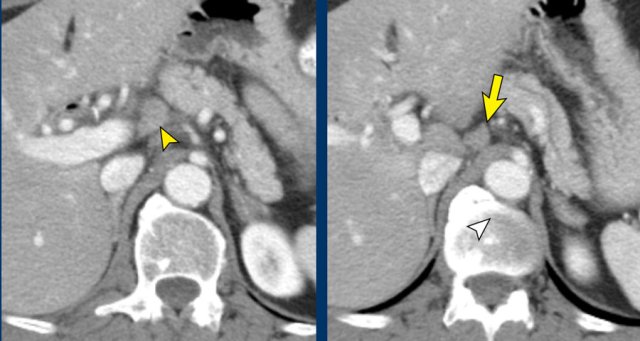

Vessel irregularity

Axial CT shows:

- Tumor in the body of the pancreas (white arrowhead).

- Focal < 90º contact with the SMA.

- More extensive 90º – 180º contact with the SMV , which is slightly narrowed and deformed (yellow arrow).

- Dilatation of the pancreatic duct

The coronal reconstruction shows:

- Vessel wall irregularity of the SMV is better appreciated on this coronal reformat (arrow).

- Tumor in the body of the pancreas (white arrowhead).

- Thrombosis in SMV side branches (small green arrows).

Coronal reformats show a large tumor originating from the pancreatic neck with an infiltrative growth pattern (figure A and B).

There is encasement of the celiac artery for 360º degrees (arrow in A).

The axial MIP at the level of the celiac artery shows narrowing of the encased common hepatic artery (arrow), highly suspicious for invasion.

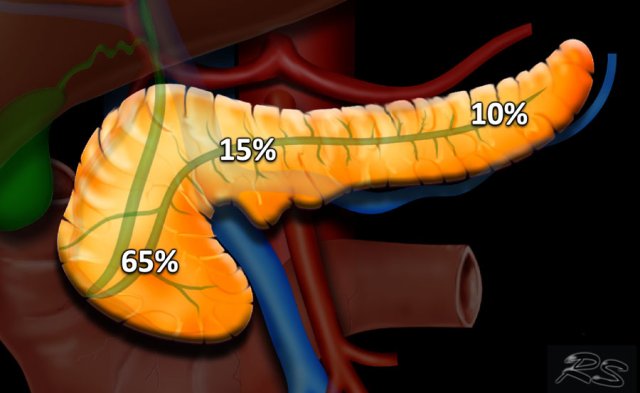

Location

65% of pancreatic adenocarcinomas are located within the head, 15% in the corpus and 10% in the tail. The remaining 10% being multifocal or diffuse (figure).

Tumors of the head usually present earlier due to obstructive jaundice. Tumors of the body and tail tend to present late and they are associated with a worse prognosis.

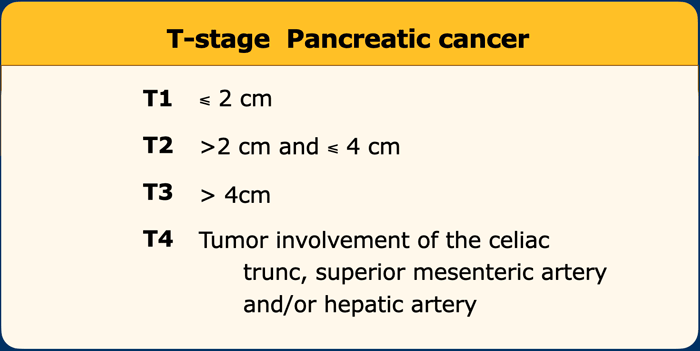

T-stage

T-staging has been simplified in the AJCC TNM-8 criteria.

The T-stage does not determine whether a tumor ia resectable or not, but has merely prognostic implications.

T2 and T3 categories are now based on size only and extrapancreatic extension is no longer part of the definition.

The rationale being that size-based definitions are more objective as it is difficult to determine extrapancreatic extension.

T4 categorization is now based on involvement of the arteries.

Resectability has been removed from the definition as resectability can be subjective and variable between institutions.

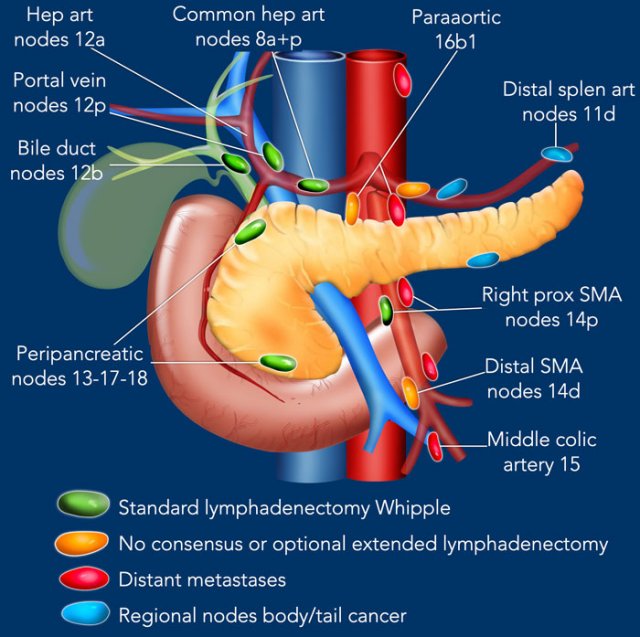

N-stage

It is important to discriminate between regional lymph nodes and extra regional lymph nodes (distant metastases).

The main extraregional locations are para-aortic and to the left of the SMA.

Suspicious nodes in these locations should be documented and sampled.

In this illustration we use the lymph node stations in pancreatic carcinoma as proposed by the Japan Pancreas Society.

A complete list is provided in the chapter on reporting. Click here.

Lymph node metastases are an important prognostic factor and occur in approximately two-thirds of patients with otherwise resectable pancreatic cancer.

Scroll through the images for the location of the lymph node stations in the axial plane.

The sensitivity of CT for detecting lymph node metastases is poor, around 15% based on a size criterium of >10mm short-axis alone.

The reason for this poor sensitivity is that small regional lymph nodes often harbor metastases, while large lymph nodes can be reactive.

Adding morphological features like rounded shape, heterogeneity, central necrosis and absence of fatty hilum, still results in a poor sensitivity with values no greater than 30%.

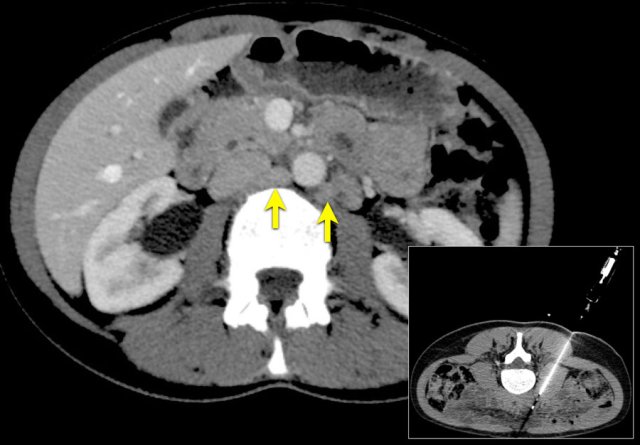

Axial CT (a) shows multipele para-aortic lymph nodes, up to a short-axis of 10mm (primary tumor in the pancreas not shown).

CT guided biopsy of a low left para-aortic lymph node was performed. Pathological analysis showed no metastasis but sarcoid.

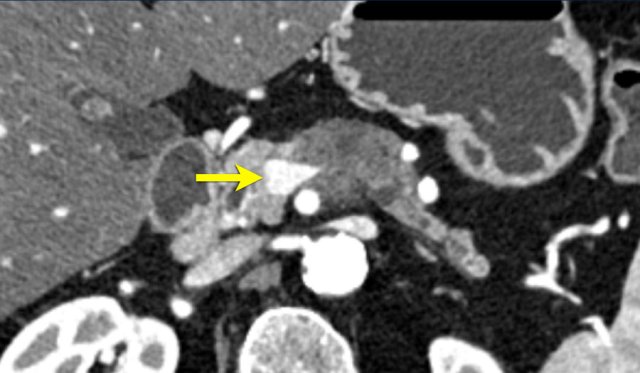

This patient had a primary tumor in the head of the pancreas (not shown).

There is a locoregional lymph node metastasis next to the portal vein (arrowhead).

A second lymph node metastasis is seen between the caudate lobe and left gastric artery (arrow).

This second lymph node metastasis is not routinely resected but may be part of an extended lymhadenectomy.

Continue with next image...

In

the chest a similar pathological lymph node was seen para-esophageal in station

8.

This was confirmed on EUS guided FNA as an extraregional lymph node metastasis. Meaning distant metastases and irresectabele disease.

M-stage

40% of patients with pancreatic cancer have distant metastases at the time of presentation. Next to distant lymph node metastases these are mainly hepatic (20-75%), peritoneal (9%) and pulmonary (<10%).

Liver metastases frequently present as multiple lesions less than 10mm in size and are predominantly in a subcapsular location. It has been hypothesized that this is a form of peritoneal spread. Subsequently the sensitivity of CT for detecting liver metastases is low, around 75%.

Furthermore over 50% of hepatic metastases are diagnosed within 6 months of resection of the primary tumor, suggesting synchronous disease and being already present at the time of initial staging.

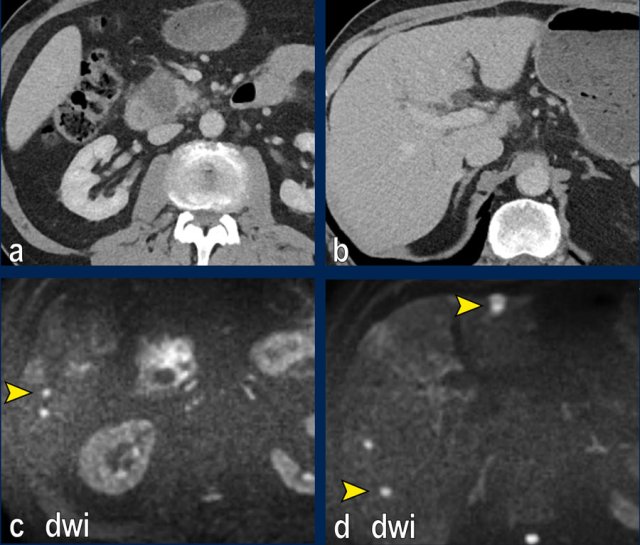

Images

The images show an axial CT (a,b) with a resectable tumor in the pancreatic head, with no signs of liver metastases.

The patient was randomized for neaoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in the PREOPANC-2 trial.

MRI for radiotherapyplanning (DWI shown in c,d) within several weeks of CT showed over 10 liver metastases.

CT is not sensitive for the detection of small peritoneal lesions, but larger lesions may be noted.

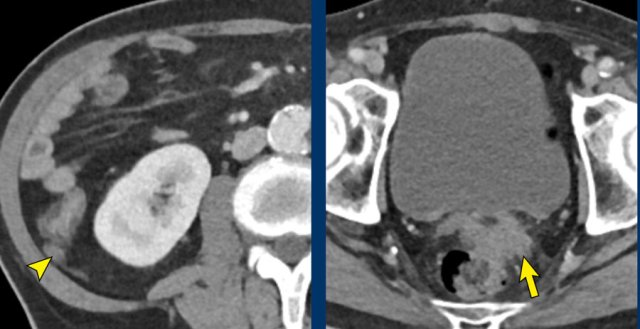

Images

Peritoneal

metastases in the right paracolic gutter (arrowhead) and in the rectovesical

space (arrow) in a patient with locally advanced pancreatic cancer (not shown).

In the presence of distant metastases curative intended treatment of LAPC (systemic

therapy with possible subsequent resection) is no longer an option.

In doubtful cases laparoscopy may confirm the diagnosis.

Additional findings of interest to the surgeon

Next to the assessment of vascular involvement the invasion of other surrounding structures and organs should be examined (see checklist).

Some

of which are directly invaded and don’t

preclude resection (for instance duodenal invasion, which is taken out in a

Whipple procedure.)

But both spread to the

transverse mesocolon and root of the mesentery are commonly overlooked and may

warrant extended resections or lead to irresectability.

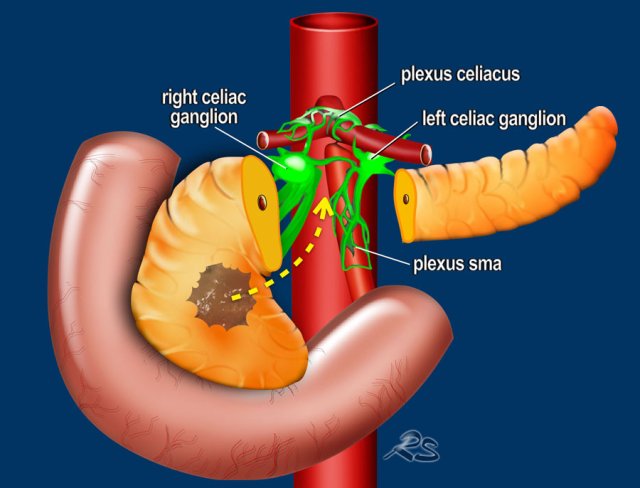

Perineural invasion

Perineural spread is a common finding in pancreatic adenocarcinoma and seen in more than half of the cases.

It is an important prognostic factor for early recurrence and metastatic disease.

On CT it is detected as infiltrating soft tissue from the edge of the tumor along known specific peripancreatic neural pathways, which extend from the pancreatic head to the SMA, celiac trunc and the common hepatic artery.

Even in small tumors this can lead to unresectable disease.

Perineural invasion (2)

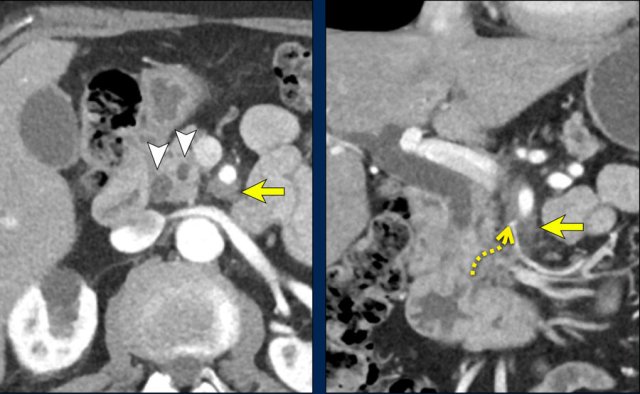

The axial image shows a double duct sign (arrowheads).

Although a mass in the pancreatic head is not seen, we must assume that there is a small tumor in the pancreatic head.

On both the axial and coronal images there is extensive soft tissue infiltration from the medial side of the pancreatic head toward the SMA (yellow arrows).

This is a typical pattern of perineural growth.

In this case leading to 90 – 180 degrees contact with the SMA.

Continue with the scroll images...

Perineural invasion (3)

These axial images are of the same patient.

Notice the large area of perineural spread.

Although there is a double duct sign and perineural tumor spread which indicates a tumor in the pancreatic head, no mass can be found on the CT.

Notice the length of the perineural tumor spread.

Perineural invasion (4)

Scroll through the coronal images.

Axial CT shows a mass in the uncinate process (arrowhead). The coronal reformat shows invasion of the mesentery as demonstrated by encasement of a major SMV tributary (arrowhead) and separate obstruction of proximal jejunal veins (arrow)

Axial CT shows a mass in the uncinate process (arrowhead). The coronal reformat shows invasion of the mesentery as demonstrated by encasement of a major SMV tributary (arrowhead) and separate obstruction of proximal jejunal veins (arrow)

Spread to root of mesentery

The root of the small bowel mesentery extends obliquely in the abdomen running from the point of termination of the duodenum at Treitz all the way to the cecum.

The SMA and the SMV and their branches are the predominant vascular structures within the mesentery.

A carcinoma of

the uncinate process can easily involve the jejunal mesentery by spreading

along this pathway.

The first jejunal branches of the SMA and SMV serve as landmarks

to identify this type of invasion (figure).

If invasion is limited resection and reconstruction may be possible, but more extensive invasion is mostly irresectable.

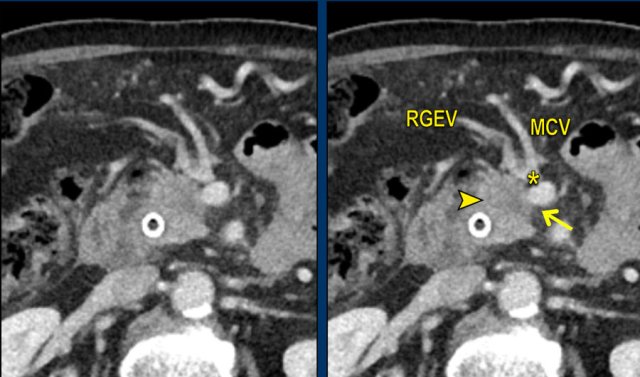

Axial CT shows a mass in the pancreatic head (arrowhead). In less then 90 degrees contact with the SMV (arrow), but also in close contact to the gastrocolic trunk (asterisk), in this case the venous confluence of the right gastopepiploic vein (RGEV) and the middle colic vein (MCV).

Axial CT shows a mass in the pancreatic head (arrowhead). In less then 90 degrees contact with the SMV (arrow), but also in close contact to the gastrocolic trunk (asterisk), in this case the venous confluence of the right gastopepiploic vein (RGEV) and the middle colic vein (MCV).

Spread to transverse mesocolon

The transverse mesocolon is in contact with the ventral side of the head of the pancreas and can be invaded by a tumor of the pancreatic head.

It can be identified on CT by following the middle colic vein and right gastro-epiloic vein to the point where they join to form the gastrocolic trunk, which is usually the last vein to drain into the SMV, on the ventral side.

Invasion of the transverse mesocolon does not necessarily preclude resection, but since additional hemicolectomy might be needed this is essential pre-operative information.

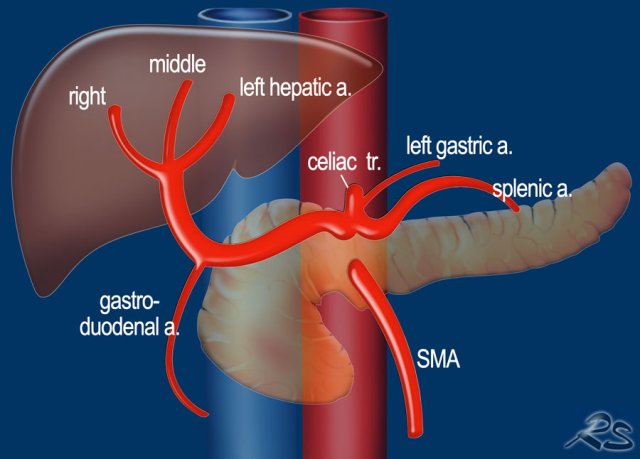

Variations of arterial anatomy

Anatomic variations

What we regard as the normal hepatic arterial anatomy is seen in only 55% of the population (figure).

Variations of the hepatic arterial anatomy are seen in approximately 40-45%.

Anomalous arteries may run in close proximity to the head of the pancreas, which predisposes them to tumor extension or predisposes them to iatrogenic injury during surgery.

Hepatic arteries with an anomalous origin can either be accessory or replaced.

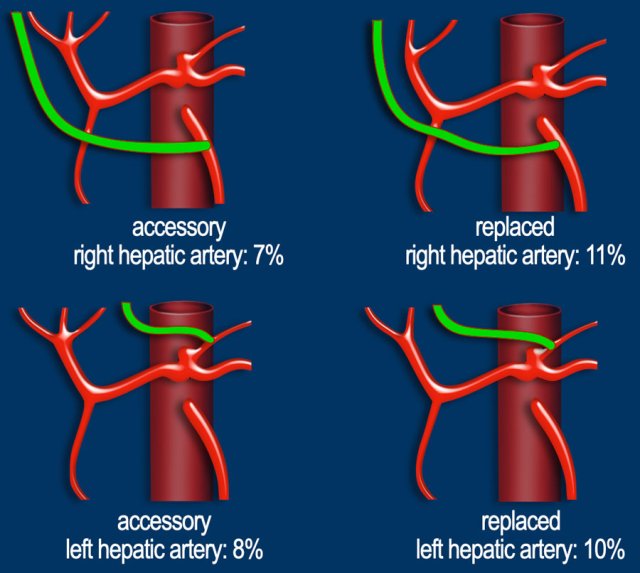

An accessory right hepatic artery is an extra right hepatic artery, while a replaced right hepatic artery has an anomalous origin and replaces the proper right hepatic artery (figure).

The most common variations are demonstrated in the illustration.

In patients planned for pancreatic surgery, it is important to look especially for an anomalous origin of the right or common hepatic artery.

These arteries originate from the right side of the SMA and run in close proximity to the head of the pancreas, which predisposes them to tumor extension or iatrogenic injury.

The reported frequencies of these specific anomalies are 11-21% and 0.5-5%.

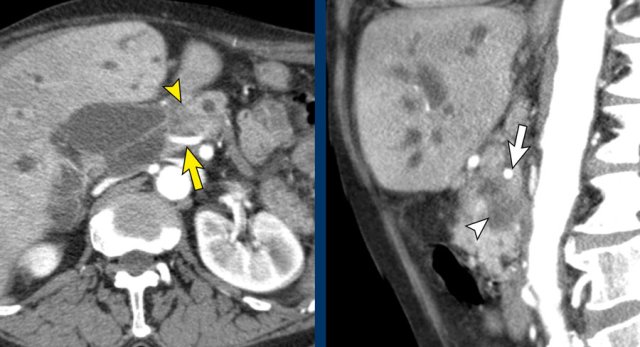

The axial CT shows a accessory right hepatic artery (yellow arrow) running in close proximity to a hypodense mass in the pancreatic head (arrowhead).

The vascular involvement is better appreciated on the sagittal reconstruction. There is 90 – 180° abutment of the replaced right hepatic artery (white arrow) by a pancreatic head adenocarcinoma (white arrowhead).

The native left hepatic artery is seen in a more anterior course, the portal vein in between.

The operation was a R1-resection.

Axial images of the same patient with annotations.

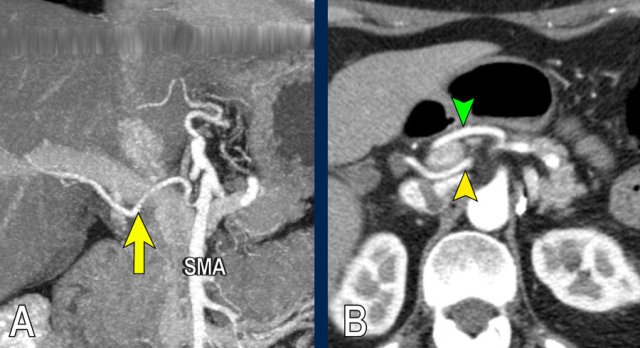

This coronal MIP shows a replaced right hepatic artery originating from the right side of the SMA (yellow arrow in A).

It is in close proximity to the pancreatic head .

The axial CT shows the course of the replaced right hepatic artery behind the portal vein (yellow arrowhead) and the native left hepatic artery running anterior to the portal vein (green arrowhead).

This was an incidental finding in a patient without pancreatic pathology.

Coronal imagers of a patient with a tumor in the pancreatic head and a accessory right hepatic artery.

Notice the abutment of the accessory artery by the tumor.

The images show an anatomical variant in which the common hepatic artery originates in total from the SMA.

The hepatic artery is seen within the pancreatic head (yellow and green arrow in B).

Celiac trunc stenosis with collateral bloodflow to the hepatic artery via the pancreaticoduodenal arcade.

Celiac trunc stenosis with collateral bloodflow to the hepatic artery via the pancreaticoduodenal arcade.

Arterial stenosis

Next step in the preoperative evaluation is to look for a stenosis of the celiac artery, which is observed in 2-8% of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Celiac artery stenosis can either be caused by compression of the median arcuate ligament or atherosclerotic disease.

A significant stenosis of the celiac artery is usually overcome by collateral bloodflow from the SMA, via the peripancreatic arcade (of Buhler) and retrograde flow in the gastroduodenal artery. Since the gastroduodenal artery is resected during pancreaticoduodenectomy the arterial blood supply to the liver is at risk if a celiac artery stenosis is not detected preoperatively.

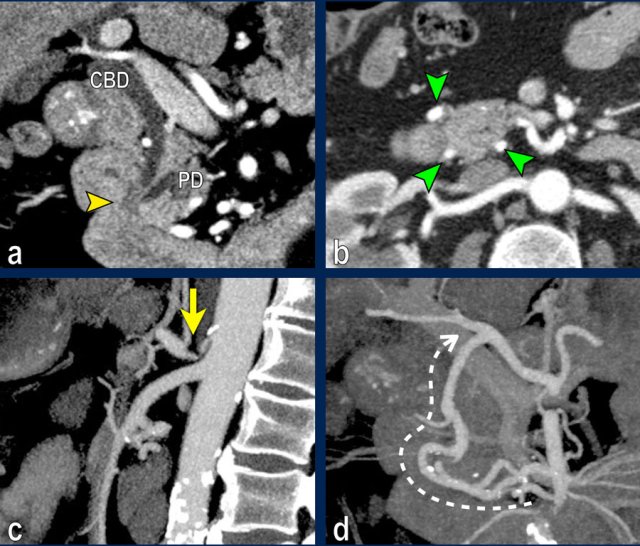

Images

The coronal reformat (a) shows a small tumor in the ampullary region (arrowhead), with obstruction of both the common bile duct (CBD) and pancreatic duct (PD). In absence of local invasion this is regarded as a resectable lesion.

The axial CT (b) however shows hypertrophy of the peripancreatic arcade (arrows), highly suggestive of a significant stenosis of the celiac trunk.

The celiac trunk stenosis is shown on sagittal MIP (arrow in c).

The collateral bloodflow to the hepatic artery via the pancreaticoduodenal arcade (stippled arrow) is nicely appreciated on a coronal MIP (d).

Re-staging after neoadjuvant treatment

In the era of neoadjuvant treatment restaging has become a hot topic and has shown some important restrictions, mainly in the differentiation of remaining fibrosis and vital tumor.

Re-staging on CT overestimates tumor size and consequently underestimates response, therefore RECIST measurements have little to no value in the absence of progression. Furthermore vascular involvement is overestimated, persisting in 80% of patients, but possibly being fibrosis instead of vital tumor.

Any reduction in vessel-tumor contact has been shown to be significantly associated with R0 resection, suggesting that this finding might be considered an indication for surgical resection in suitable candidates.

The role of re-staging CT at this time is to rule out disease progression and if so surgical exploration should be considered. Data on the additional value of DWI or PET-CT are still limited.

Images

Axial CT (a) before neoadjuvant treatment shows a tumor on the medial side of the pancreatic head (arrowhead), irresectable based on extensive perineural growth with 360 degrees encasement of the SMA (arrow in b, coronal reformat).

Follow-up CT after 8 cycli of FOLFIRINOX (c,d) shows stable disease with persistent encasement of the SMA. The process was resectable on explorative laparotomy. T3bN2R0 on pathological exam.

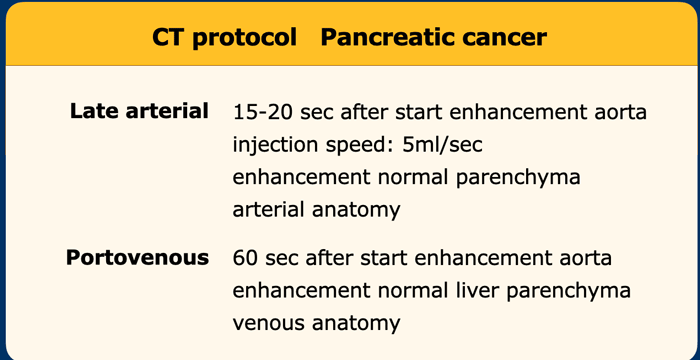

Imaging

CT protocol

Local staging should be done on a high quality pancreatic CT, consisting of a late arterial and portal venous phase.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma typically presents as a hypodense hypovascular mass, which is best appreciated in the late arterial phase. This is also best for the arterial anatomy to look ofr variants and stenoses.

The portovenous phase is best for detection of liver metastases and detection of venous stenoses and encasement.

For protocol recommendations click here

CT is the workhorse in staging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

It is most widely used and best validated.

CT can assess local extension and distant metastases, with accuracies of up to 77% for predicting resectability and 93% for predicting irresectability.

Role of MRI

MRI is used for the characterization of indeterminate liver lesions on CT, as of yet there is no evidence supporting for staging of the liver with MRI in all patients.

Furthermore MRI can be used in the characterization of mainly cystic pancreatic lesions, a subject beyond the scope of this article.

MRI allows improved detection of liver metastases, with reported sensitivities of 85-100%. With 10-25% of MRI being positive for liver metastases after initial negative CT. These data are however based on small retrospective studies.

In the era of neoadjuvant treatment the role of MRI is still debated, given the fact that in >40% of small liver lesions histological proof cannot be obtained via a percutaneous biopsy.

Surgical treatment

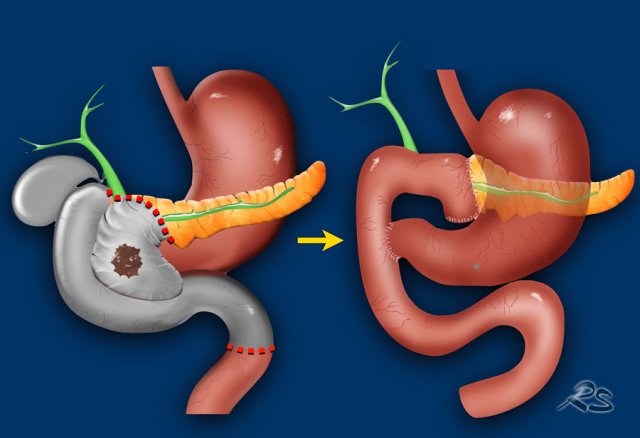

Whipple procedure

A Whipple procedure is an operation in which the pancreatic head with the carcinoma and the distal choledochal duct is resected combined with a small distal part of the stomach, the duodenum and a small part of the proximal jejunum.

The stomach, proximal choledochal duct and the body of the pancreas are connected to the jejunum.

Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy

A pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) is almost the same operation but the pylorus is preserved.

Distal or left pancreatectomy

Operation for a tumor in the pancreatic body or tail. It is carried out with or without splenectomy.

Total pancreatectomy

Combination of Whipple and distal pancreatectomy.

Reporting

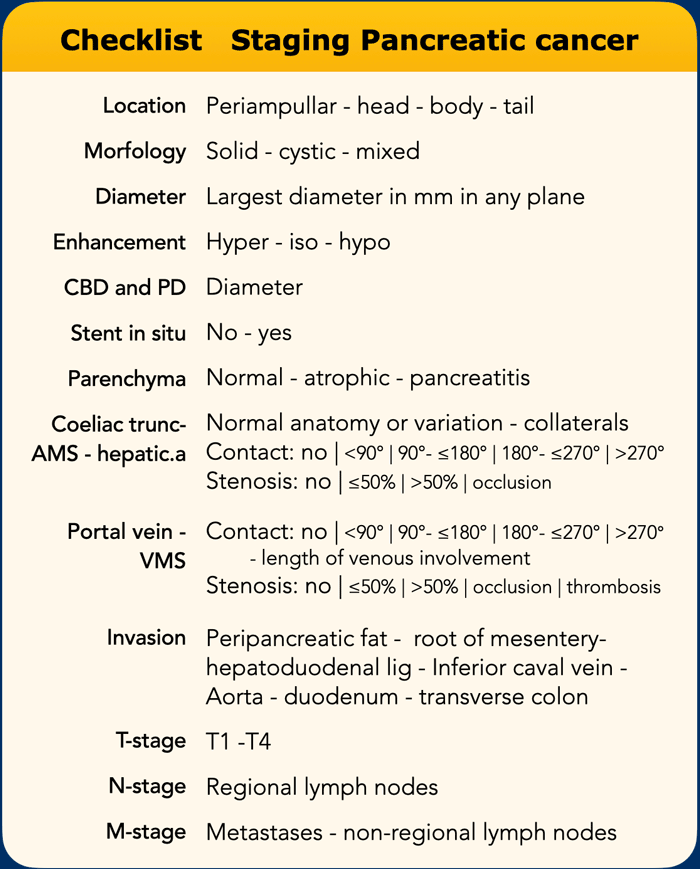

Checklist

This list contains all the items that need to be examined.

In the conclusion of the radiology report mention the most important items.

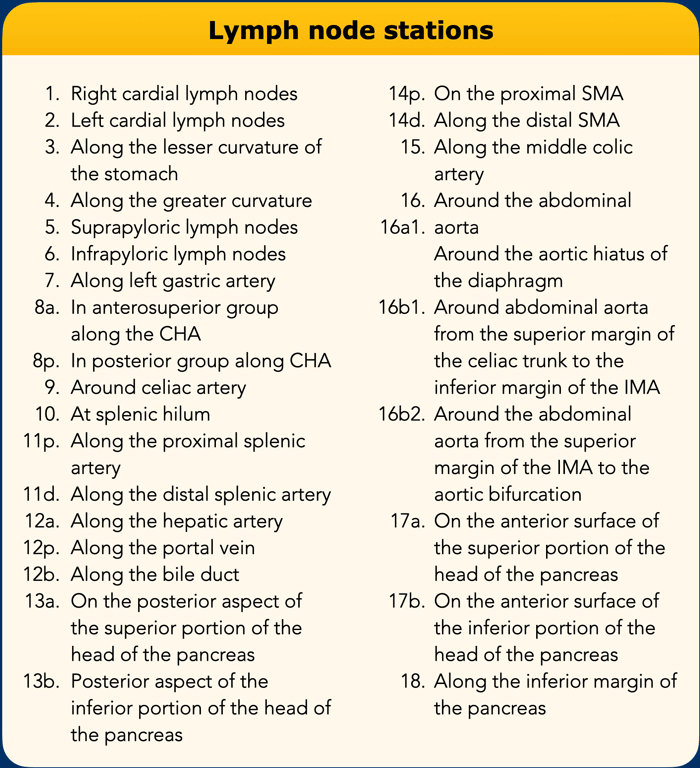

Lymph node stations in pancreatic carcinoma

Lymph node stations in pancreatic carcinoma as proposed by the Japan Pancreas Society.

Video presentation by Frank Wessels

Case 1 - resectable cancer

This is case 1 of a series of demonstration on how to stage pancreatic cancer.

More videos will come shortly.