Dynamic Rectal examination

Tjeerd Wiersma

Radiology department of the Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem, The Netherlands.

Publicationdate

Dynamic rectal examination (DRE) is also known as defecography or proctography.

DRE provides a dynamic assessment of the act of defecation by recording the rectal expulsion of a barium paste that approximates the consistency of feces.

DRE provides qualitative and quantitative information on the function of anorectal and pelvic floor function, and the effectiveness of the anal sphincter and rectal evacuation.

by Tjeerd Wiersma

Dynamic Rectal Examination

Indications

Indications for dynamic rectal examination are:

- outlet obstruction (disorder of defecatory or rectal evacuation), caused by intussusception, enterocele or spastic pelvic floor syndrome.

- to distinguish between anterior rectocele and enterocele

- fecal incontinence combined with outlet obstruction in intra-anal intussusception.

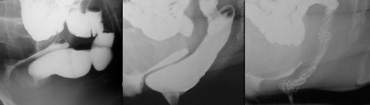

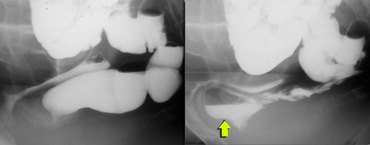

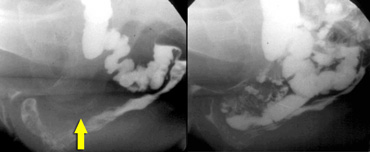

LEFT: Pathology is suspected because of a great distance between rectum and vagina. No oral contrast had been given. RIGHT: After ingestion of liquid barium contrast a large enterocele is seen.

LEFT: Pathology is suspected because of a great distance between rectum and vagina. No oral contrast had been given. RIGHT: After ingestion of liquid barium contrast a large enterocele is seen.

Technique

Two hours prior to the examination the patient ingests 135 ml of liquid barium contrast to opacify the small bowel (figure).

Rectal contrast can be administered without rectal preparation.

The ideal rectal contrast has to simulate stool in weight and consistency.

In our experience, Evacu-Paste? 100 (E-Z-EM Inc., Westbury, NY, USA) is a convenient paste.

The barium paste is injected until the patient experiences discomfort due to rectal distension or until about 250 ml has been instilled.

In females the vagina is coated with 30 ml amidotrizoic acid 50% solution gel.

It is applied by means of a syringe with a soft pediatric enema tip.

The use of tampons and gauzes soaked in barium should be avoided, because they can impaire pelvic-function.

After sufficient filling of the rectum, the patient is asked to sit on a special commode.

The fluoroscopic screening of the rectum and the function of the pelvic musculature and the continence mechanism is assessed.

The duration of examination is about 15 minutes.

Imaging

Examinations includes a number of standard images and maneuvers.

Initially the patient is screened in lateral projection at rest without consciously contracting any pelvic muscles and a spot film is taken.

The patient then maximally contracts the pelvic floor muscles ('squeeze') which results in a more tense muscular diaphragm and in elevation of the entire pelvic floor a spot film or video is taken.

Finally the patient is asked to empty the rectum as completely as possible.

An estimate of the completeness of defecation and measurement of pelvic floor descent can be made.

Morphological abnormalities are usually discernible during this part of procedure.

It is important that the patient is sitting during the procedure, since much of physiological nature of defecation is lost when the patient is lying down.

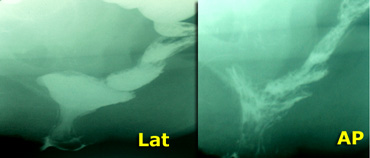

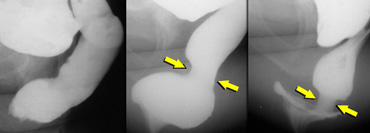

Additional oblique or anteroposterior (AP) views should be taken of any unexplained radiographic feature seen on the lateral views (figure).

An S-shaped rectum may simulate an intussusception in lateral projection.

On the left lateral and an AP-view of a patient with an intussuseption on both views.

On the left lateral and an AP-view of a patient with an S-shaped rectum which simulates an intussuseption on the lateral view.

Recording

The whole procedure of DRE should be recorded on video or DVD.

Dynamic recording of the fluoroscopic images enables the examiner to follow the movements of the rectum, facilitating the diagnosis of rectocele, enterocele and intussusception, as well as to evaluate the function of the anal sphincter.

Digitization of fluoroscopic image or digital substraction may facilitate direct screen measurements of angles.

Some patients give a history of various unusual maneuvers (digital support of vagina or perineum) to aid defecation.

Allowing the patients to demonstrate the maneuvers during the examination may facilitate the radiological documentation of the mode of action.

Since a number of treatment methods, which successfully can restore the dynamics of rectal evacuation, have been developed speed and completeness of rectal emptying is clinically important and therefore need to be recorded.

Normal findings

At rest: distance between vagina and ventral rectal wall

Findings of abnormalities

Rectocele

A rectocele can be defined as an anterior or posterior bulge of the rectal wall

beyond the extrapolated line of the wall (Fig. 1).

The formation of an anterior rectocele is often apparent during defecation and may reflect

relative weakness of the rectovaginal septum.

At the end of the defecation, residual rectal contents may be left in the rectocele ('trapping').

Significantly more anterior rectoceles were found in female patients and in female control subjects than in males.

Anterior rectoceles may occur in individuals without complaints of the anorectal region

and should therefore particularly in women be considered as a posiible normal phenomenon.

The main symptoms associated with a rectocele are usually a feeling of incomplete bowel movement

often requiring digital pressure to the vagina or perineum to facilitate emptying, together with aching

after a bowel movement.

Barium trapping in the rectocele is considered to be important in explaining the repeated

sensation of rectal fullness after defecation.

In our own series no correlation could be found between the size of the rectocele and the symptoms, so we do not grade rectoceles anymore.

It has been suggested that rectoceles may be the result of repeated straining secondary

to a preexisting disorder (f.e. spastic pelvic floor syndrome) of defecation rather than to

the rectocele being the primary cause of the obstructive symptoms.

This may also explain why rectocele repair is often unsuccessful in relieving symptoms.

When surgical repair of a rectocele detected at physical examination is considered, preoperative

DRE should be performed to exclude other causes of obstructed defecation (intussusception or enterocele).

DRE demonstration of a rectal intussusception may change the operative procedure e.g. to

correct the intussusception instead of the rectocele.

In patients with an anterior rectocele, in whom other causes of obstructed defecation are ruled out, surgical rectocele repair should be considered.

In our opinion there are two indications for operating on an anterior rectocele.

First: if a patient needs vaginal digital support to facilitate defecation.

Second: in cases of disturbed sexual intercourse.

Posterior rectoceles are incidental findings and not related to clinical symptoms (figure).

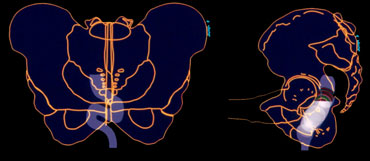

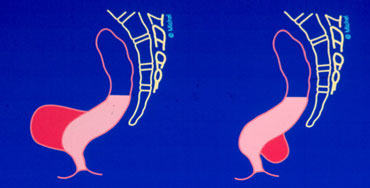

1 : Intra-rectal intussusception, 2 : Intra-anal intussusception, 3 : Extra-anal intussusception (rectal prolapse)

1 : Intra-rectal intussusception, 2 : Intra-anal intussusception, 3 : Extra-anal intussusception (rectal prolapse)

Intussusception

Intussusception of the rectum is an invagination of the rectal wall, which begins as a circular fold 6 to 8 cm up in the rectum and develops into a condition in which the entire rectal wall folds in towards the rectal lumen.

The intussusception can be intra-rectal, intra-anal or finally extra-anal as a rectal prolapse (figure).

In connection with straining this folding inwards progresses and deepens to form a ring pocket, so that it finally fills the entire ampulla.

This may reach down to, into or through the anal canal (rectal prolapse).

A minimal folding inwards which disappears after the bolus has passed is probably caused by a transient prolapse of the rectal wall and should not be considered pathological.

The most common complaint of the patient with intussusception is:

- Difficulty in bowel emptying.

- Pain, blood loss upon defecation

- Incontinence of gas and/or feces

- Mucus discharge which often leads to pruritis ani.

Upon hard straining the obstructive sensation increases.

In order to empty their bowels many patients have to extract the feces manually, while others have to exert pressure with their hands about the anus and perineum.

Enemas may be ineffective.

Rectal prolapse (extra-anal intussusception) may be transient and difficult to reproduce, while intrarectal intussusception may be overlooked on clinical examination and is seldom revealed by proctoscopy.

When the intussusception reaches into the anal canal it leads to maximal dilatation.

These patients often complain of fecal incontinence in between defecation while they have the feeling of an obstacle or incomplete emptying during defecation.

A longstanding intussusception may lead to the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.

There is seldom doubt regarding the clinical diagnosis of complete rectal prolapse.

Lesser grades of prolapse, however, can present a variety of difficulties.

Oblique or anteroposterior (AP) views can be necessary too, due to the AP view provides a more reliable image of intra-anal intussusception than the standard lateral view during evacuation.

Enterocele

An enterocele is a peritoneal sac that has herniated downwards along the ventral rectal wall.

As DRE is routinely performed with small bowel and vaginal contrast, loops of small bowel are then seen to fill the gap between the vagina and the rectum.

Grade 1 is maximally reaching down to the distal half of the vagina, and partial or complete reduction of the rectal lumen.

Grade 2 is as grade 1, but reaching down to the perineum.

Grade 3 is protruding out of the anal canal to form a rectal prolapse.

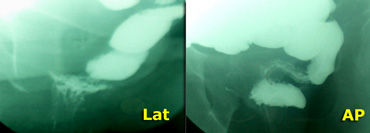

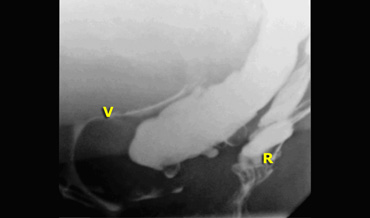

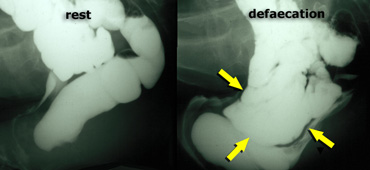

Normal findings at rest (left); during defecation there is a rectocele, that is pushed downward by an enterocele .

Normal findings at rest (left); during defecation there is a rectocele, that is pushed downward by an enterocele .

Sometimes the enterocele is identified only at the end of the defecation, after repeated straining.

An enterocele may be pressed into the direction of the introitus vaginae.

If there is an associated rectocele, this can be pushed downward by the enterocele and finally evacuated (figure).

Clinically it can be difficult to diagnose an enterocele.

Patients with previous pelvic surgery are predisposed to the formation of an enterocele.

In female patients with constipation there is a higher incidence of severe enteroceles in patients with a hysterectomy (22%) compared to the group without hysterectomy (9%).

Chronically increased intra-abdominal pressure may cause an enterocele with or without a previous pelvic operation.

A sigmoidocele is a prolapse of redundant sigmoid colon into a deep pouch of Douglas.

It is less common than an enterocele.

Spastic pelvic floor syndrome

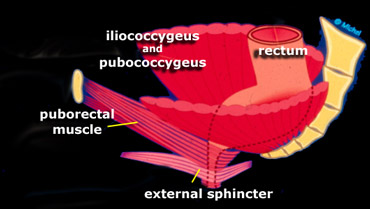

On the left a schematic lateral view on the levator ani and external sphincter ani muscles is shown.

The puborectal muscle should be contracted at rest (sharp anorectal angle).

During defecation the puborectal muscle should relax allowing passage of the stool.

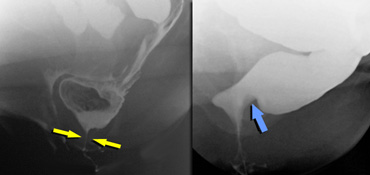

LEFT: Hypertonic sphincter (during defecation).RIGHT: Impression of hypertonic puborectal muscle (non-relaxing during defecation).

LEFT: Hypertonic sphincter (during defecation).RIGHT: Impression of hypertonic puborectal muscle (non-relaxing during defecation).

Spastic pelvic floor syndrome denotes a persistent contraction of the pelvic floor muscles during defaecation.

It represents a functional disorder of the pelvic floor muscles causing an outlet obstruction.

The question arises, however, whether persistent contraction is due to the conscious action of an embarrassed patient, thus only occurring during the investigation, or whether it really represents a functional disorder of the pelvic floor muscle resulting in outlet obstruction.

The etiology is unknown.

Psychological factors may play a role.

The anorectal angle (ARA) normally increases on straining as a result of relaxation of the puborectal muscle. The extent of increase may range from 20? to 40?.

In a small group of patients with impaired evacuation, DRE demonstrated either an unchanged or decreased ARA on straining or defecation, which findings frequently result from a persistent or paradoxical increase of the puborectal muscle impression.

This appearance is often quite persistent and the evacuation may only be achieved after multiple attempts at straining and defecation.