Gallbladder obstruction

by Julien Puylaert

Medical center Haaglanden in the Hague and Academical Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Most gallstones that we find with ultrasound are asymptomatic and should be left untreated.

However when gallstones obstruct the gallbladder or the common bile duct they become symptomatic.

In part 2 we will discuss stones that obstruct the biliary ducts.

In part 1 we will discuss gallstones that obstruct the gallbladder.

We will focus on:

- How to determine whether gallstones are symptomatic or not.

- How to diagnose stones in the neck of the gallbladder or in the cystic duct.

- How to find silent witnesses of symptomatic stones.

- Different forms of acute cholecystitis and its complications.

For critical comments and additional remarks: j.puylaert@gmail.com

Introduction

Symptomatic stones

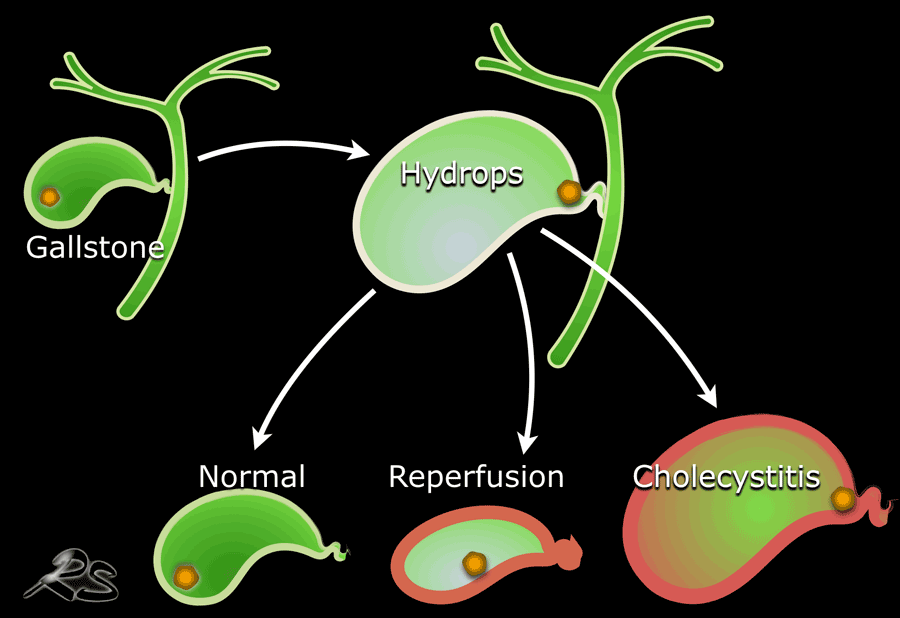

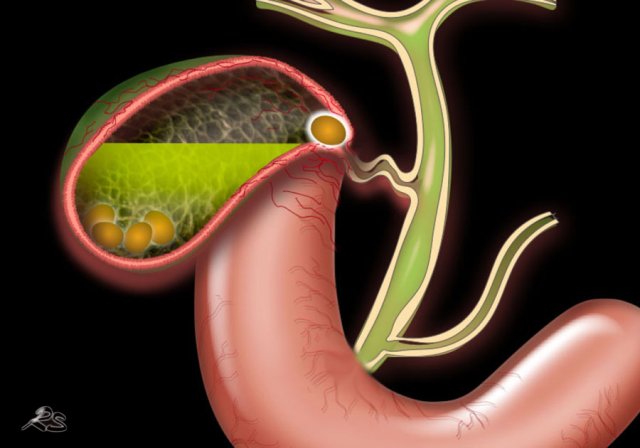

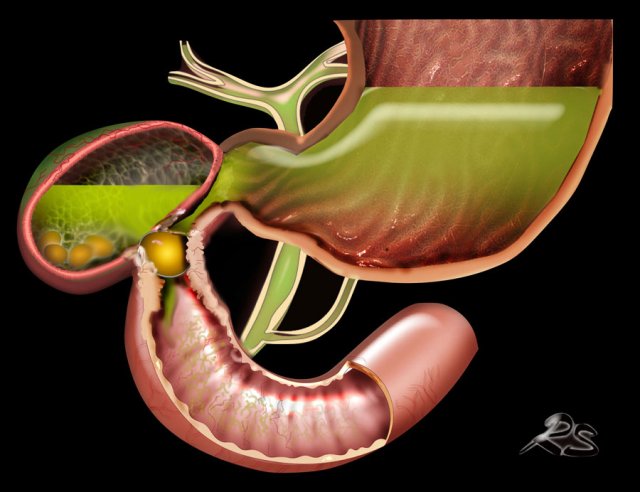

Gallstones become symptomatic when they obstruct the gallbladder or the common bile duct (CBD).

Intermittent obstruction results in a simple biliary colic.

An impacted stone obstructing the gallbladder results in acute hydrops.

Persistent production of mucus causes high intraluminal pressure, leading to relative ischemia of the wall.

Here another overview of the different pathways when there is an impacted stone in the gallbladder neck:

- The stone becomes dislodged before ischemia of the gallbladder wall has occurred and no secondary wall thickening is seen.

- The stone becomes dislodged and relief of intraluminal pressure is followed by transient reperfusion edema of the wall, which then disappears and the gallbladder becomes normal. The reperfusion is the silent witness of a symptomatic stone.

- Obstruction continues and acute cholecystitis develops.

It is important to realize that patients only experience pain during the hydrops phase.

Laboratory data only show leucocytosis and the CRP remains normal.

After the hydrops has disappeared, the colic is over but the patient often experiences a “sore feeling” for a while.

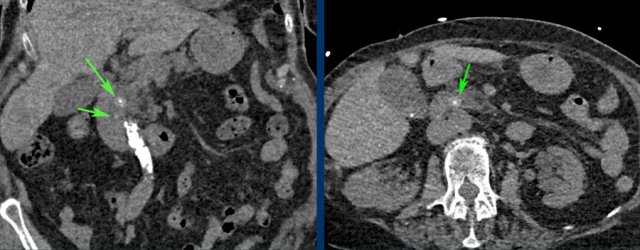

CT for suspected aortic dissection. The only relevant finding were two CBD stones best visible on the non-contrast series (arrows).

CT for suspected aortic dissection. The only relevant finding were two CBD stones best visible on the non-contrast series (arrows).

Asymptomatic stones

The majority of patients with gallstones however will not experience any problems with these stones during their lifetime.

Therefore, asymptomatic gallstones detected coincidentally during US or CT, performed for other reasons, are left untreated.

The literature indicates that over 20 % of patients undergoing cholecystectomy, have unchanged symptoms after the operation, suggesting that the diagnosis of symptomatic gallstone disease was not correctly made.

On the other hand, the diagnosis of acute gallstone disease can be missed because the doctor mistakes the symptoms for another condition e.g. acute cardiovascular disease.

This explains why around 15 % of patients with an acute biliary colic are initially referred to the cardiologist.

Biliary colic

When a gallstone intermittently obstructs the gallbladder or the CBD, a biliary colic will follow.

Symptoms are often typical with episodes of intense pain in the upper abdomen, radiating to the back and to the right side, but also sometimes to the left side.

Patients are often nauseous and may collapse from the pain.

Not rarely, the pain awakes patients from their sleep.

During a biliary colic, patients preferably do not sit still, and have an urge to move and walk around.

They continuously “try to find a position to tolerate the pain”.

When the stone is not obstructing the gallbladder neck at the time of the examination, it will be difficult to make the diagnosis of symptomatic gallstone disease and you will be able to compress the gallbladder fundus (fig).

However in patients with a history of typical, uncomplicated colicky attacks without signs of cholestasis, in whom stones in the gallbladder are demonstrated on US, the indication for cholecystectomy is evident.

On the other hand, in patients with atypical symptoms, it is not always clear whether the US-demonstrated gallstones are actually the cause of the patient’s symptoms, resulting in quite a few patients who have unchanged symptoms after cholecystectomy.

However in patients with a history of typical, uncomplicated colicky attacks without signs of cholestasis, in whom stones in the gallbladder are demonstrated on US, the indication for cholecystectomy is evident (fig).

On the other hand, in patients with atypical symptoms, it is not always clear whether the US-demonstrated gallstones are actually the cause of the patient’s symptoms, resulting in quite a few patients who have unchanged symptoms after cholecystectomy.

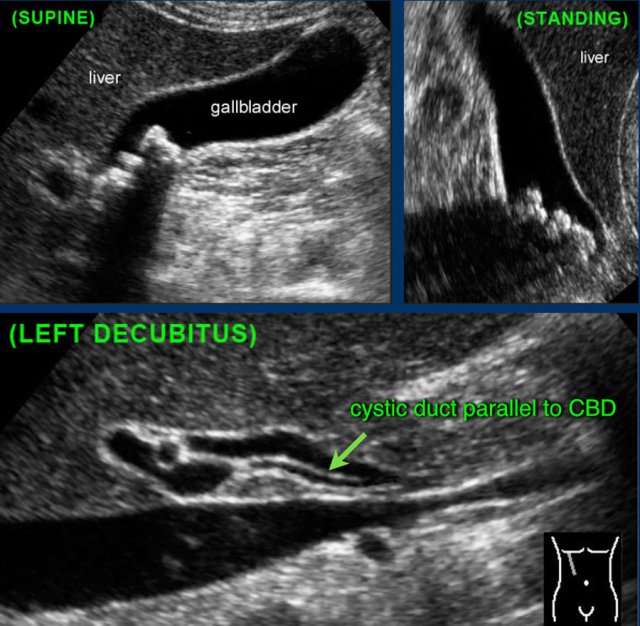

This patient had typical colic pain a few days before the examination.

In the standing position there are no obstructing stones in the gallbladder neck.

Even the cystic duct was seen with its typical course parallel to de common bile duct.

In case of an obstructing CBD stone, you will also be able to compress the gallbladder fundus, but there will be typical lab-findings with elevated liver function tests.

Dilatation of the biliary tree will develop within a very short time and the gallbladder may become dilated.

The intraluminal pressure however is much less than in isolated obstruction of the gallbladder (fig).

US scanning during an episode of pain can be very helpful.

Patients who undergo US during an acute biliary colic, at that particular moment –invariably- either show a hydropic gallbladder or dilated biliary ducts.

These US signs however may rapidly disappear when the obstruction is relieved, either spontaneously or due to spasmolytic medication, which is usaully given at the ER.

Acute Hydrops

Hydrops sign

Persistent obstruction of the gallbladder results in a hydropic gallbladder due to ongoing mucus production by the gallbladder mucosa.

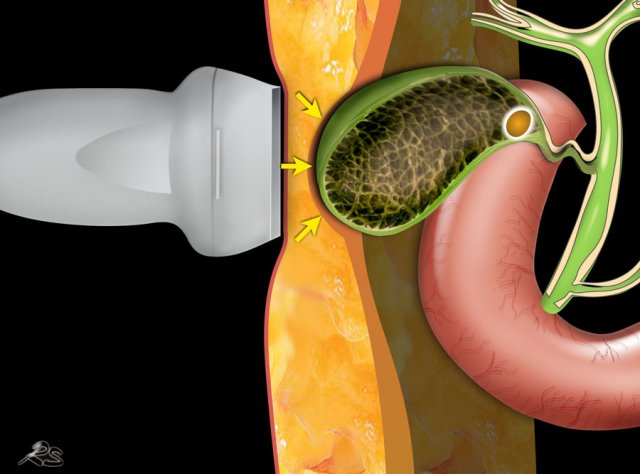

The hydrops sign is tested by applying graded compression over the gallbladder.

The hydrops-sign is positive if the gallbladder during compression “bulges” into the abdominal wall and keeps its rounded contour (fig).

This is best seen in expiration, when the abdominal wall muscles relax.

Here we can see how the hydropic gallbladder will keeps its rounded shape during compression.

If the obstruction carries on long enough, the high intraluminal pressure may lead to temporary ischemia of the gallbladder wall.

The US signs of acute hydrops due to an impacted stone obstructing the gallbladder, are given in the table.

The non-compressibility of the gallbladder and direkt demonstration of the impacted stone in the galbladder neck or cystic duct are the most valuable signs (****).

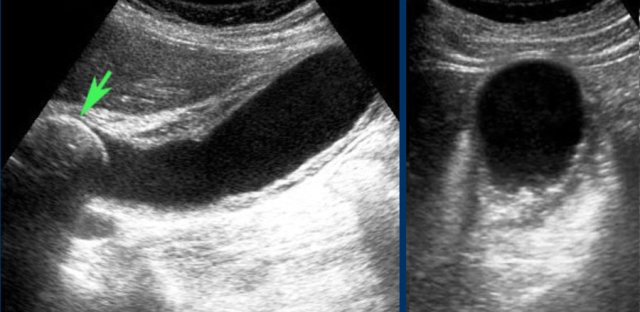

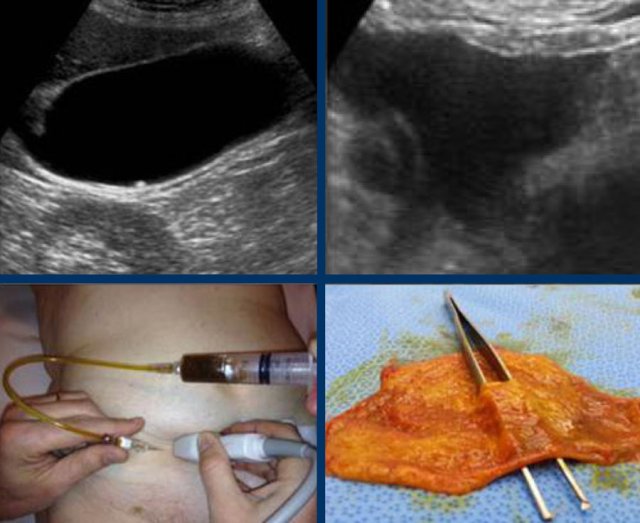

Here images of a patient with acute hydrops of the gallbladder, visualized in its longitudinal and its axial plane.

The obstructing stone is impacted (arrow).

Note that during compression the hydropic gallbladder bulges into the abdominal wall (arrowheads), indicating high intraluminal pressure.

It is however not always possible to visualize the hydrops-sign reliably, especially when the gallbladder lies high under the right costal arch.

Also the impacted stone may be impossible to visualize in large persons, due to its deep location, far from the transducer.

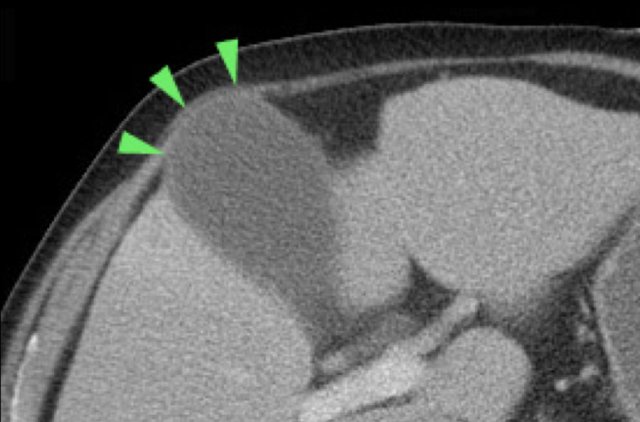

Not infrequently, also on CT scan hydrops of the gallbladder may be identified (fig), but often complementary US is very useful.

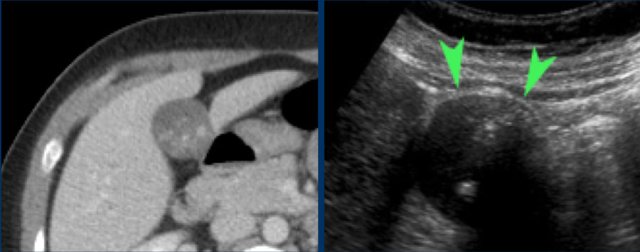

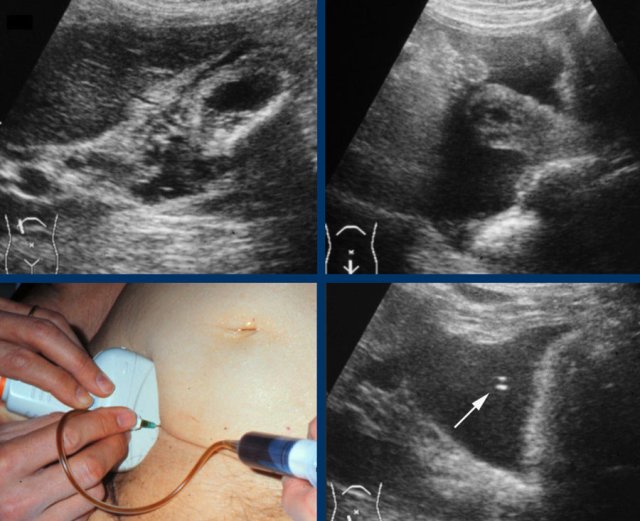

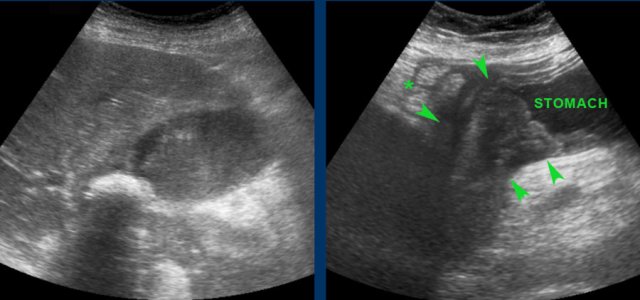

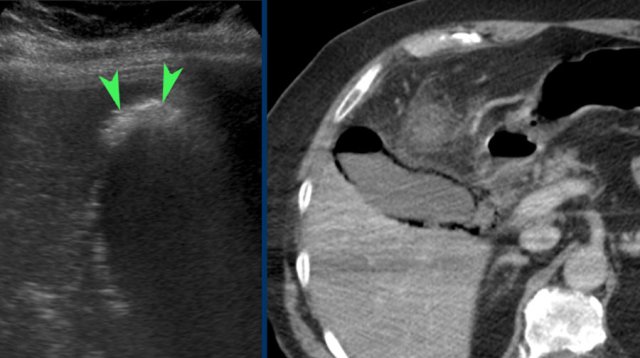

Here images of a patient with clinically suspected stomach perforation.

CT shows some stones in a rounded gallbladder.

Complementary US unequivocally demonstrates hydrops (arrowheads).

Even in the case, when there is intervening liver tissue between the abdominal wall and the gallbladder, an indirect “hydrops-sign” can be demonstrated.

The left image shows a gallbladder that keeps its rounded shape, without and during compression, and bulges into the soft interposing liver tissue and abdominal wall.

Likewise, the absence of hydrops can be demonstrated, even when there is intervening liver tissue, which is soft during compression (image on the right).

How to demonstrate an impacted stone

In this patient examination in the decubitus position could not identify an obstructing stone due to the presence of multiple stones.

If US in the standing position shows that all loose stones have migrated to the fundus, the patient is asked to lie down again, immediately turning on its left side.

In this way the stones, will remain in the fundus, allowing better visualization of the gallbladder neck and cystic duct (fig).

All stones have moved to the fundus except the impacted stone (arrow).

There is gallbladder wall thickening indicating developing cholecystitis (CRP was 110).

Note that in case of inspissated, viscous bile, stones may change position very slowly, sometimes taking several minutes to go to the lowest point.

For this reason, we ask patients with suspected gallstones, always to sit or stand up while waiting for their US examination.

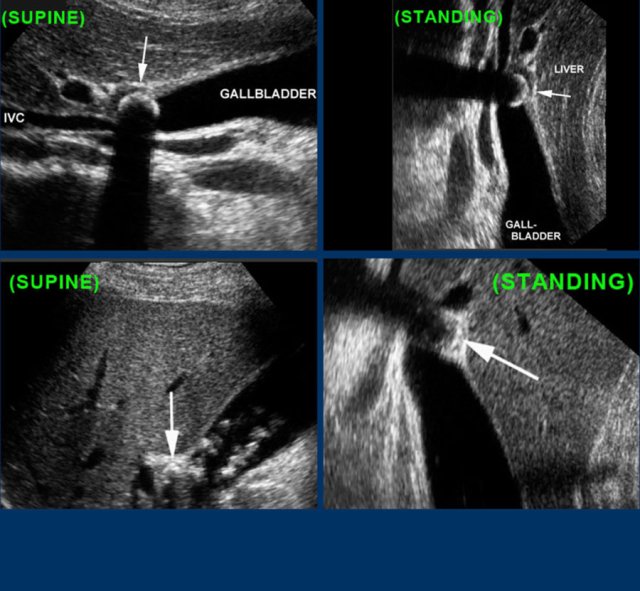

Here two examples of impacted stone visualized during biliary colic in different patients.

In the supine position a stone (arrow) is demonstrated in the gallbladder neck.

After standing up, bending over and walking, the stone (arrow) does not fall down, and therefore must be impacted.

Stones in the cystic duct are sometimes not demonstrable in the US plane of the longitudinal axis of the gallbladder.

Here images of a patieny with acute hydrops due to an impacted stone.

The impacted stone could not be visualized in the longitudinal axis of the gallbladder, due to its medial position in the cystic duct (arrow).

Large diameter

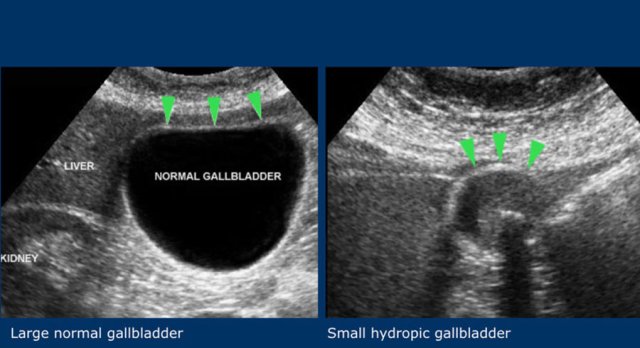

The third sign is a large transverse diameter of the gallbladder.

This is not a very reliable sign, since gallbladder diameters have a wide range.

A 2.5 cm gallbladder can be hydropic and a 5 cm diameter gallbladder can be normal (fig).

Therefore, non-compressibility and preservation of the round shape during compression, remain the US hallmarks of hydrops.

US-Murphy-sign

Finally, a sign of acute hydrops is circumscribed tenderness on pressure with the US probe over the gallbladder fundus, the so-called US-Murphy-sign.

Although often present, this sign is not always reliable.

Especially older patients with an acute cholecystitis have difficulties exactly indicating the area of maximum tenderness.

In addition, if another condition like a duodenal ulcer, acute pancreatitis or an acute appendicitis, causes the right upper quadrant pain, the US Murphy sign may be false-positive because of the close proximity of the gallbladder.

Secondary wall thickening of the gallbladder may add to the confusion.

US performed after the biliary colic

Silent witnesses

What may cause considerable diagnostic confusion, is the fact that -in daily practice- most US examinations in patients with suspected symptomatic gallstones, are performed after the symptoms have subsided, with intervals varying from hours to weeks.

Patients also may have received spasmolytic therapy, which may cause the muscle spasm to relax and bile to pass, changing the US image which can appear atypical and even confusing.

There are silent witnesses that indicate that the patient had an obstructing stone with hydrops of the gallbladder (table).

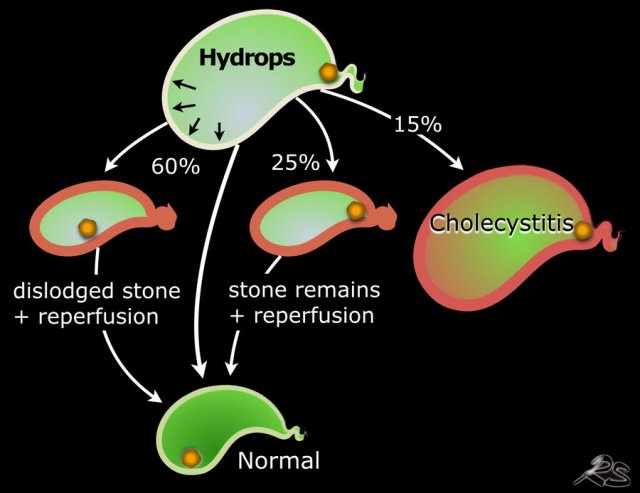

Follow up in 100 patients presenting with acute hydrops at the ER treated with spasmolytics and not immediately operated. In 15 acute cholecystitis developed. In 25 the stone remained in place, but bile can pass and hydrops disappears. In 60 patients the stone becomes dislodged and the galbladder returns to normal sometimes with a period of reperfusion edema.

Follow up in 100 patients presenting with acute hydrops at the ER treated with spasmolytics and not immediately operated. In 15 acute cholecystitis developed. In 25 the stone remained in place, but bile can pass and hydrops disappears. In 60 patients the stone becomes dislodged and the galbladder returns to normal sometimes with a period of reperfusion edema.

The natural course of a biliary colic due to an obstructing stone in the gallbladder neck has various pathways.

During the colic the stone is impacted in the gallbladder neck with acute hydrops.

Persistent production of mucinous fluid causes high intraluminal pressure, leading to ischemia of the wall.

- The stone may become dislodged with relief of intraluminal pressure followed by reperfusion edema of the wall and then later the galbladder may return to normal.

- The stone is loose before ischemia of the gallbladder wall has occurred and no secondary wall thickening is seen.

- The stone remains impacted but allows passage of bile along the stone. There is reperfusion edema, but the hydrops is gone. Eventually later the galbladder may return to normal.

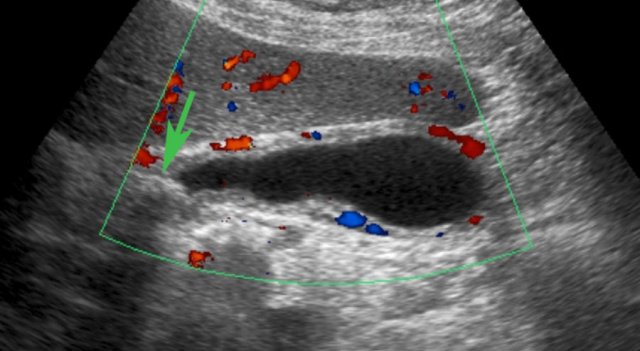

US performed 5 hours after the pain episode. There is both reperfusion edema and hyperemia of the gallbladder wall. The obstructing stone (arrow) is still visible in the neck, but there was no hydrops

US performed 5 hours after the pain episode. There is both reperfusion edema and hyperemia of the gallbladder wall. The obstructing stone (arrow) is still visible in the neck, but there was no hydrops

Reperfusion edema

It is important to realize that patients only experience pain during the hydrops phase.

Laboratory data only show leucocytosis and the CRP remains normal.

Soon, the intraluminal pressure will be so high that relative ischemia of the stretched thin gallbladder wall may occur.

If the stone is disimpacted or in another way again allows passage of bile to the cystic duct, which may happen spontaneously or due to spasmolytic therapy, edema of the gallbladder wall may develop very rapidly (fig).

This edema disappears again within 12-48 hours and is reperfusion-edema, secondary to the episode of ischemia.

Sometimes also the secondary hyperemia can be found by Doppler US (fig).

After the hydrops has disappeared, the colic is over but the patient often experiences a “sore feeling” for a while.

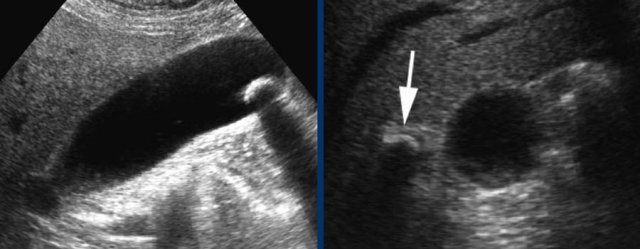

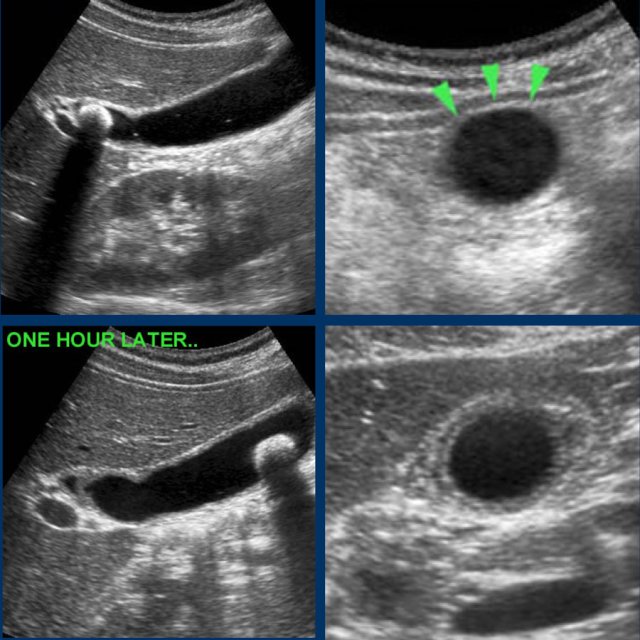

Images of a young woman with a biliary colic for 8 hours.

US shows an impacted stone and hydrops.

The patient went walking for an hour and US was repeated.

The stone was loose, and reperfusion edema was visible as silent witnesses of the colic.

CRP remained normal.

When the hydrops has disappeared, patients do not have colicky pain any more.

However patients often have a vague “sore” feeling in the upper abdomen as if someone has “stumped them in the belly”.

It is obvious that it is essential to integrate the patient’s history, the laboratory data and the US findings in the final report of the US examination.

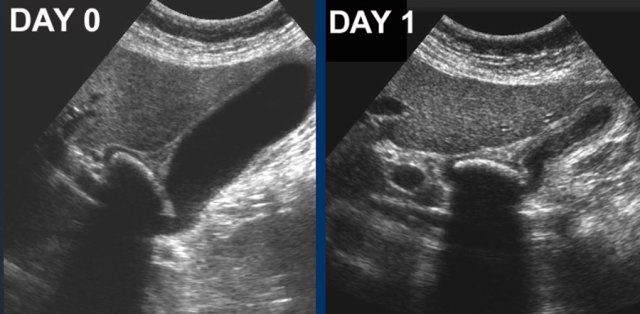

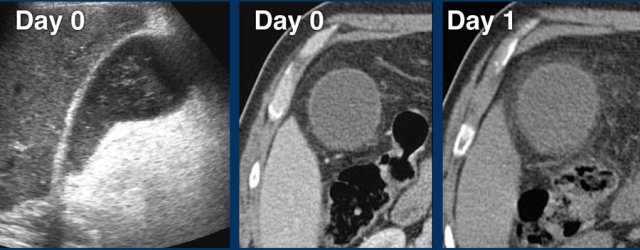

At day 0 there is acute hydrops due to an impacted stone.

One day later, the patient is symptom free.

The stone is still in place, but apparently allows passage of bile to the cystic duct, since hydrops has disappeared.

Reperfusion edema and sludge are the silent witnesses of the previous attack .

CRP remained normal.

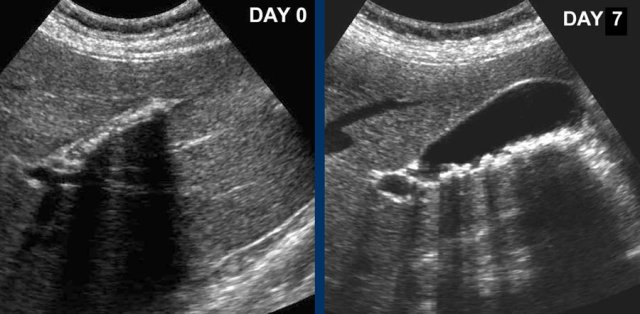

Silent witness of previous attack.

US, performed 24 hours after colicky attack shows a contracted gallbladder with multiple small stones in patient who did not eat.

Seven days later the gallbladder is deployed again (visualized in again fasting patient).

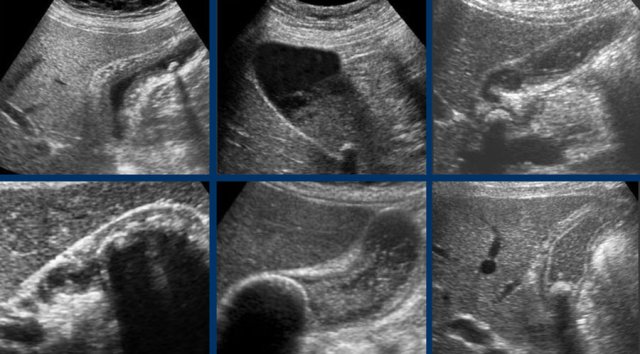

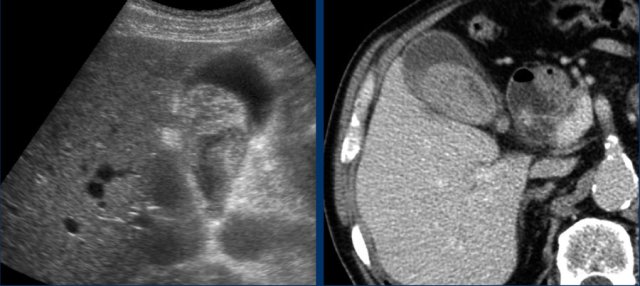

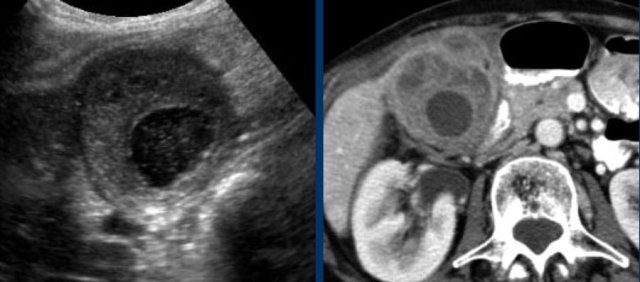

Silent witnesses of a biliary colic in six different patient.

US was done 6-12 hours after the pain episode.

All patients were symptom free at the moment of US.

Of course, not all patients are so lucky that their biliary colic spontaneously subsides.

Of all patients presenting with a biliary colic, in a minority (10-15 %) progression to an acute cholecystitis is seen.

Acute Cholecystitis

If the stone keeps obstructing the gallbladder neck or cystic duct, bacterial infection of the stagnating bile and mucus may turn an acute hydrops into an acute cholecystitis.

Since this a gradual process, the US signs of acute cholecystitis evolve gradually and are superimposed on the signs of acute hydrops

In this table the US signs of acute cholecystitis superimposed on the signs of acute hydrops.

The additional US signs of cholecystitis are:

- gallbladder wall thickening, which is often layered

- occurrence of sludge as a sign of prolonged stasis

- hypervascularity of the gallbladder wall

- eventually inflamed fat around the gallbladder fundus which represents the omentum migrating towards the site of imminent perforation

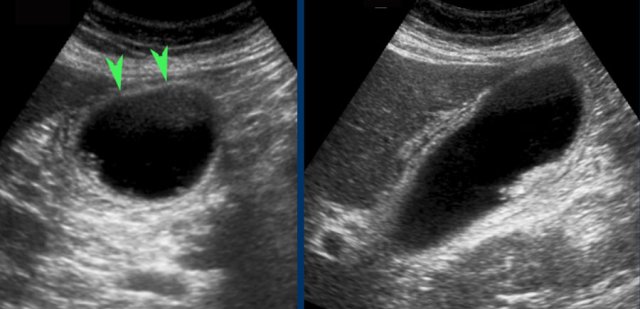

Here images of a patient with early acute cholecystitis.

Note the obstructing stone (arrow), gallbladder wall thickening and bulging of the gallbladder into the abdominal wall during compression, indicating high intraluminal pressure.

CRP was 110, confirming the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis.

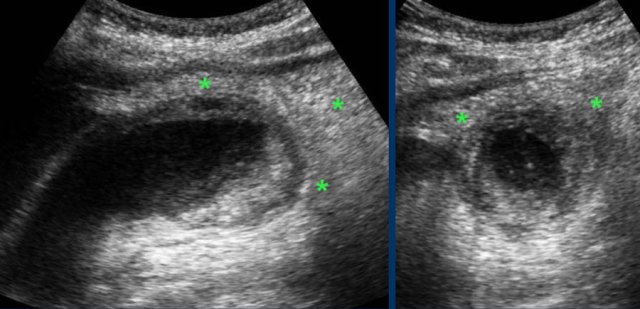

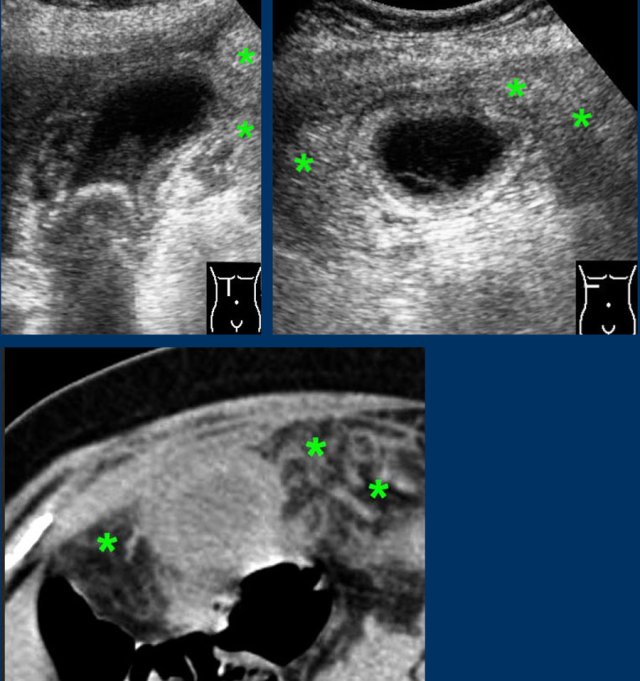

Advanced cholecystitis with inflamed fat ( asterisks) around the gallbladder fundus.

This represents the omentum, migrating towards the gallbladder in order to wall-off a possible perforation.

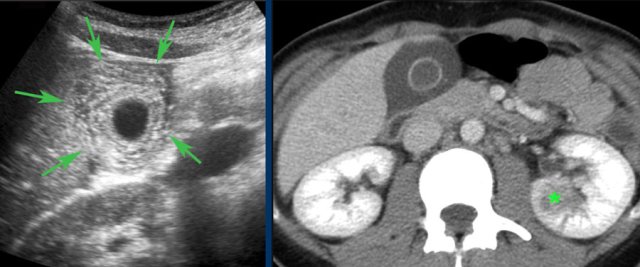

Bacteremia in a patient with lobar nephritis with reactive gallbladder wall thickening simulating acute cholecystitis

Bacteremia in a patient with lobar nephritis with reactive gallbladder wall thickening simulating acute cholecystitis

However, these additional US signs are not always reliable.

- Sludge may be the result of chronic stasis due to fasting

- Gallbladder wall thickening has several causes other than acute cholecystitis (fig).

These images are of a very ill young lady with diffuse abdominal pain and a CRP of 430.

US shows massive edematous wall thickening of the gallbladder, which has a small lumen and contains no stones.

CT reveals lobar nephritis (asterisk) as the cause of the patient’s symptoms and high CRP.

The gallbladder wall thickening is secondary to the bacterial inflammation.

After antibiotics, complete normalization of gallbladder and kidneys.

Here images of an old lady (79 yrs) with acute RUQ pain.

Large, however non-hydropic gallbladder (arrowheads) with mobile stones and edematous wall thickening.

Lab showed CRP 3 and a serum amylase of 985.

Diagnosis: biliary pancreatitis with secondary thickening of the gallbladder wall.

Obese patient with acute epigastric pain.

US showed gallstones and wall thickening, suggestive for acute cholecystitis.

Subsequent CT revealed the true nature of the symptoms: acute biliary pancreatitis with secondary gallbladder wall thickening.

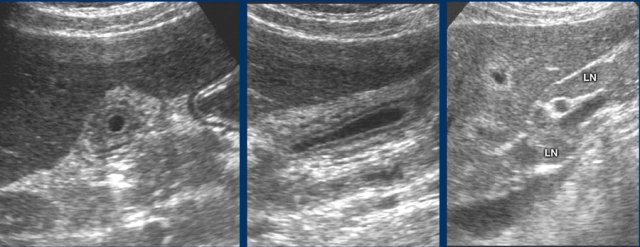

Here a patient with malaise, RUQ-pain and severe liver function abnormalities.

US shows small gallbladder with layered wall thickening and enlarged periportal lymph nodes.

Diagnosis: acute hepatitis A.

Differentiation Hydrops - Acute Cholecystitis

More important than the additional US signs in the differentiation of hydrops versus cholecystitis, are the clinical signs and laboratory findings: fever and elevated infection parameters.

It must be stressed that especially in the elderly the development from acute hydrops into acute cholecystitis is insidious and often subclinical.

The pain is often much less that the original colicky attack and fever is often absent.

This underlines the important role of repeated CRP.

Elevation of the CRP –in general- precedes the clinical symptoms.

If the patient presents late, the gallbladder may show impressive morphological changes.

Somewhat confusing may be the fact that in advanced cholecystitis, there can be a less prominent US-hydrops sign, because the diseased wall is not capable of producing mucus anymore and the intraluminal pressure has decreased.

The images show a longstanding acute cholecystitis.

Note the large area of inflamed and indurated fat (asterisks) and the relatively small, somewhat compressible gallbladder.

This reflects a lumen filled with pus where the diseased mucosa is not capable of producing mucus under pressure anymore.

Drainage revealed pus.

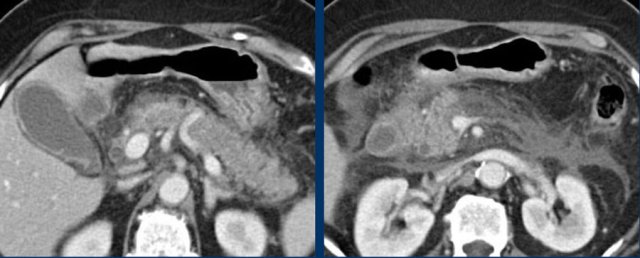

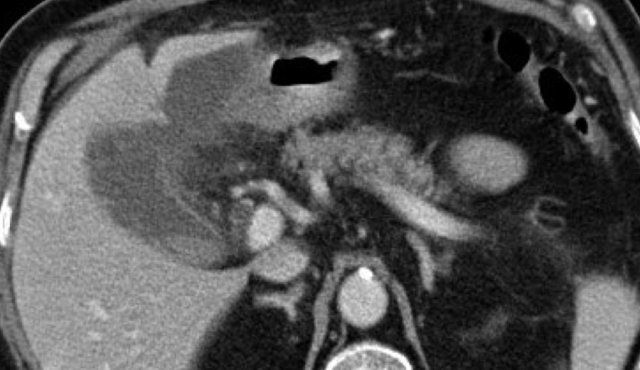

CT in acute cholecystitis

CT can be very helpful in cases with a non-diagnostic US.

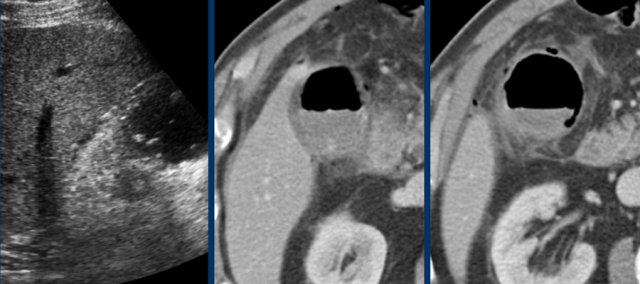

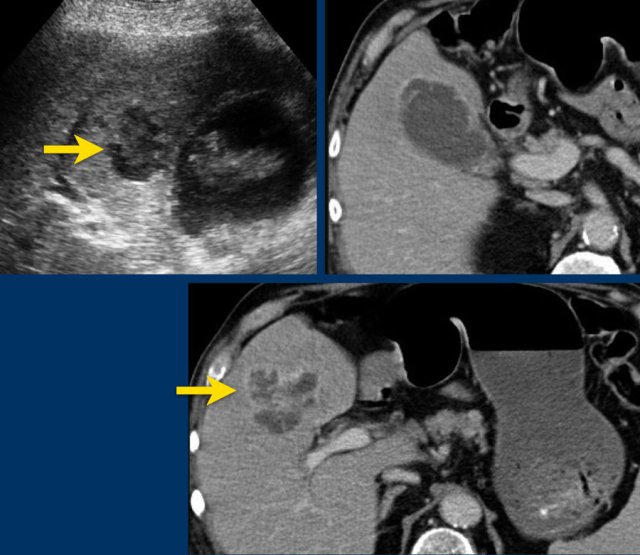

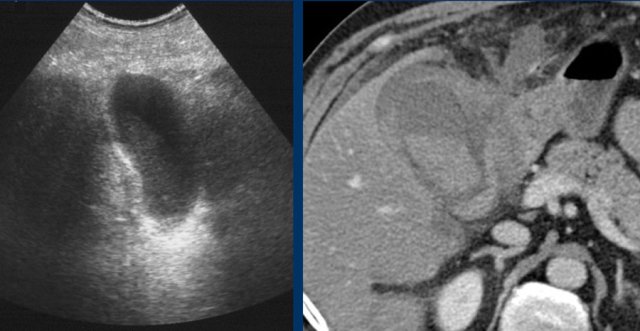

These images are of an obese patient with acute RUQ pain for 6 hours. CRP 2 .

US shows a large gallbladder with sludge, no stones were visualized.

Compression of the gallbladder is unreliable due to the high position under the right costal arch.

No other US abnormalities.

CT, performed the same day, shows a large gallbladder with only discrete pericholecystic changes and no other explanation for the symptoms.

The next day CRP is 105 and repeated non-contrast CT shows a fuzzy corona around the gallbladder.

Subsequent surgery confirmed early acute cholecystitis due to a small stone in the cystic duct.

Special forms of cholecystitis

Emphysematous cholecystitis. US shows air in the gallbladder fundus (arrowheads). CT confirms both intraluminal and intramural air.

Emphysematous cholecystitis. US shows air in the gallbladder fundus (arrowheads). CT confirms both intraluminal and intramural air.

Emphysematous cholecystitis

This special form of cholecystitis is usually –but not always- found in older diabetics and has characteristic US and CT features (fig).

Because the air indicates wall necrosis, acute cholecystectomy is usually advised, but successful percutaneous drainage is a good alternative, because surgery is often very risky in these diabetic and often otherwise severely compromised patients.

These images are of a non-diabetic patient with severe pain RUQ, CRP 190 and WBC of 19.

US noted weird aspect of the gallbladder with hyperechoic sludge and bright reflections in the wall.

CT showed emphysematous cholecystitis with also free air in the peritoneal cavity.

Conventional cholecystectomy revealed necrotizing cholecystitis with peritoneal contamination.

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis. US only shows a sludge-like mass. CT scan demonstrates hyperdense blood within the lumen and an irregular wall. Cholecystectomy was technically very difficult.

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis. US only shows a sludge-like mass. CT scan demonstrates hyperdense blood within the lumen and an irregular wall. Cholecystectomy was technically very difficult.

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis

Hemorrhagic cholecystitis is rare and seen when gallbladder wall necrosis has led to intraluminal bleeding

It is more frequent in patients with anticoagulant therapy.

US is usually aspecific but may show a large mass of sludge-like material and an irregular wall.

CT shows hyperdense, non-attenuating masses within the gallbladder lumen (fig).

Since hemorrhage is the result of ischemic necrosis of the gallbladder wall, this should preferably not be treated with percutaneous drainage, although cholecystectomy may also be quite difficult.

This is another hemorrhagic cholecystitis in a patient on salicylates.

The CRP was 150.

Immediate laparoscopic cholecystectomy was done.

The ydrops was confirmed and peroperative puncture revealed blood.

The surgery was complicated by a large post-operative hematoma.

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis

This is a rare, but well recognized benign form of protracted cholecystitis.

It is possibly the result of multiple episodes of destructive inflammation due to the presence of stones.

It is important not to misdiagnose this entity as malignancy.

These images are of a 82 year old female, who woke up at four o'clock in the morning with excruciating pain in the upper abdomen.

Her lab-findings at admission (8 hours after the pain started) were normal.

US showed a large but non-hydropic gallbladder with one little stone.

No obstructing stone was seen.

There was some free fluid, which at puncture turned out to be bile.

CT was done but did not yield extra information.

At laparoscopic cholecystectomy free perforation was found with 150 ml of bile intra-abdominally.

Another free perforated cholecystitis.

The decompressed gallbladder has a relatively small lumen and shows an irregular and edematous wall.

There is free intra-peritoneal fluid around the uterus, which at US guided puncture is identified as bile.

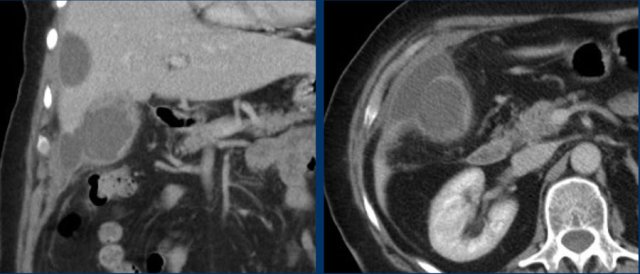

Ill patient with pain RUQ since 4 days, CRP 450 and leuko 14.

CT shows local perforation at the fundus with a not well-defined fluid-collection under the left liver lobe.

Immediate open cholecystectomy revealed perforated cholecystitis and severe purulent contamination of the peritoneal cavity.

If not timely operated, free perforation may eventually lead to distant abscess formation, often with a different location and aspect than the pericholecystic abscesses from complicated cholecystitis (fig).

There is a pericholecystic abscess as well as a distant, perihepatic abscess in perforated cholecystitis.

Antibiotics were given and only the gallbladder was drained.

Abscess in the liver adjacent to the gallbladder in acute cholecystitis, visible on both US and CT.

Percutaneous drainage of the gallbladder was done.

The abscess drained itself into the gallbladder lumen.

Cholecystitis mimicking malignancy

Acute cholecystitis sometimes is not recognized clinically, especially in the elderly, and may then be treated with antibiotics more than once.

This may cause mitigation and alteration of the normal inflammatory process leading to unusual US and CT findings.

In such cases not infrequently the diagnosis of gallbladder malignancy is suggested which may lead to ill-advised major surgery.

Keep in mind that gallbladder carcinoma in the Western world is very rare, is usually inoperable at presentation and has a poor prognosis anyway.

The combination of clinical history, US and CT image, and the follow-up in time, can prevent unnecessary major surgery.

Acalculous cholecystitis

Acalculous cholecystitis is a confusing entity.

True acalculous, non-obstructive cholecystitis is extremely rare and is the result of primary ischemic necrosis of the gallbladder due to an episode of low-flow state, comparable with non-obstructive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) leading to small bowel infarction.

It is often seen in older patients with other debilitating disease or after severe trauma.

The treatment is acute cholecystectomy.

Most patients diagnosed as “acalculous cholecystitis” are in fact patients with acute hydrops or cholecystitis in whom no stones can be found by US or CT, and also not at operation or in the pathological specimen.

However, when US unequivocally demonstrates hydrops in a patient, it is clear that there must be some sort of luminal obstruction, probably due to a very small stone or some sludge in combination with a narrow cystic duct.

Because of the obstructive origin, these cases have the same risk of complications as acute calculous cholecystitis and should thus be treated the same.

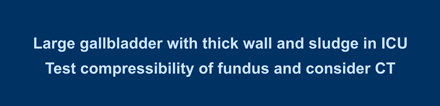

Another confusing and frequent pitfall is the large gallbladder filled with sludge and a thickened wall, often found in patients in the ICU.

In case of a high CRP, this is often misdiagnosed and mistreated as acalculous cholecystitis.

To avoid this pitfall, it is essential to test US compressibility of the gallbladder fundus and to perform CT to detect possible alternative explanations for the symptoms and the high CRP.

Fistula formation

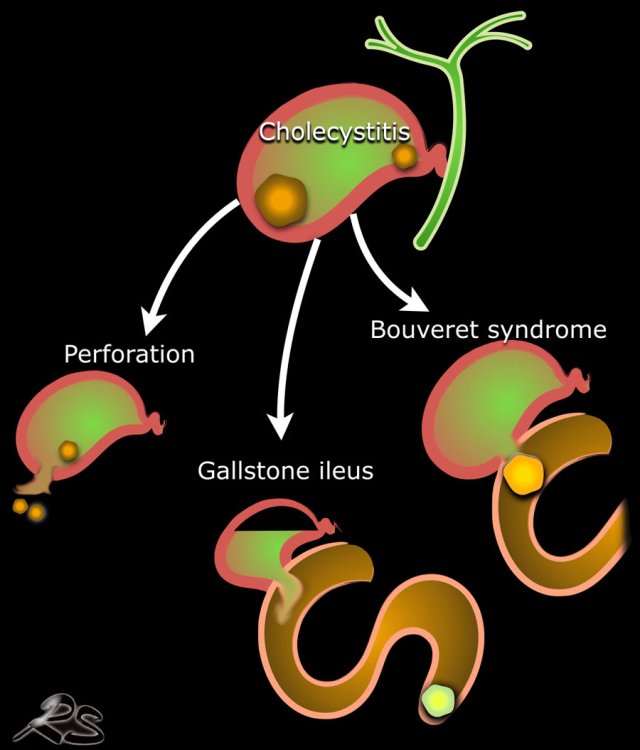

Acute cholecystitis can be complicated by perforation.

Most cases of perforated cholecystitis progress slowly and perforation is walled-off with local abscess formation.

Free perforation in acute cholecystitis is quite rare (as we discussed earlier).

Undiagnosed or untreated cholecystitis may also lead to fistula formation to the duodenum.

This is an uncommon complication, but when it occurs, most frequently there is passage of the stone to the small bowel, where it gets stuck and causes a gallstone ileus.

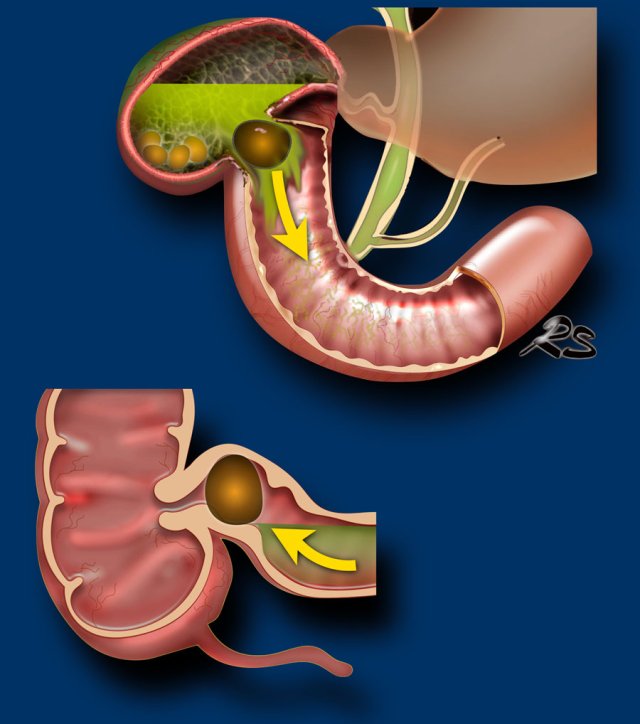

In rare cases of duodenal fistulisation, a large gallstone may get “stuck” at the fistula to the duodenum.

Due to secondary inflammatory and fibrous tissue, this may eventually lead to stenosis and obstruction.

This special situation is called “Bouveret syndrome” and its main clinical feature is gastric outlet obstruction.

Gallstone ileus

When untreated, acute cholecystitis may lead to new complications.

Purulent gallbladder contents including the gallstones may eventually evacuate to the duodenum or sometimes to the colon

This occurs usually in older patients, in whom cholecystitis often has remained undiagnosed and/or untreated.

It usually concerns a large stone, which classically gets stuck at the ileocecal valve, but in fact in most cases the stone obstructs the small bowel higher up in the ileum or even jejunum.

The diagnosis in most cases is much easier made using CT than US.

Play the video.

The key finding is the air in the gallbladder.

Play the video.

The key finding is the air in the gallbladder.

Scroll through the images (on a Mac with two fingers).

This is a typical gallstone ileus.

Notice how difficult it is to detect the non-calcified stone.

Bouveret syndrome

In rare cases of duodenal fistulisation, a large gallstone may get “stuck” during a longstanding fistulisation process.

Due to secondary inflammatory and fibrous tissue, this may eventually lead to stenosis and obstruction of the duodenum.

This special situation is called “Bouveret syndrome” and its main clinical feature is gastric outlet obstruction (fig).

Although rare, it is very important to make the correct diagnosis, because cholecystectomy is very dangerous and should be avoided.

If the stone cannot be removed endoscopically, the best solution is a gastrojejunostomy.

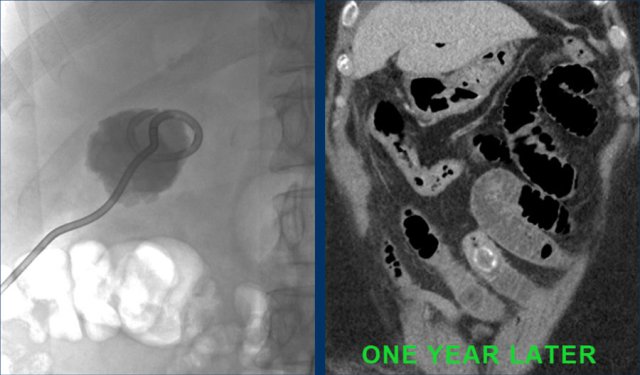

This is a patient with intermittent gastric retention and a low CRP.

Scroll through the images.

What are the findings?

A large stone got “stuck” in the fistulous tract from the deformed gallbladder to the duodenum.

Secondary wall thickening of the duodenum (arrowheads) and surrounding inflammatory and fibrous tissue, cause intermittent gastric retention with vomiting.

Images of an elderly lady, presenting with gastric retention and vomiting.

CRP was 55, but was documented to be 160 a few days earlier.

US shows a large stone in a gallbladder filled with debris-like material, and an irregular wall.

The stomach is dilated and there is remarkable wall thickening of the duodenum (arrowheads) and surrounding inflammation (asterisk).

Gastroscopy was done for suspected malignancy, but biopsy only revealed inflammation.

Continue with the CT.

CT confirms the diagnosis of Bouveret syndrome.

Percutaneous gallbladder drainage relieved the symptoms of gastric retention.

One year later, the stone apparently managed to evacuate to the duodenal lumen, and she developed a classic gallstone-ileus as yet, which was operated successfully.

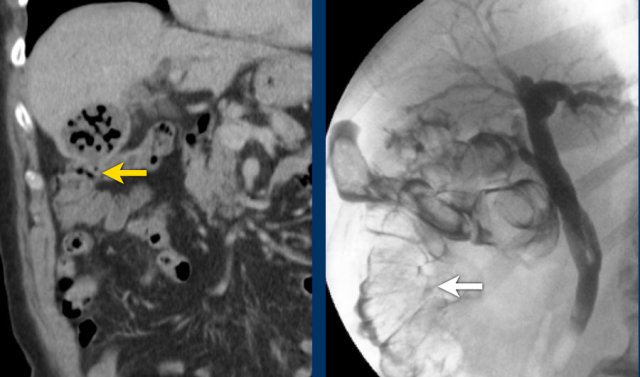

Fistula to the colon

This rare situation often develops subclinically and insidiously. In purulent cholecystitis the pus evacuates to the colon, however evacuation of the stones may take months or even years.

Patients eventually may develop chronic diarrhoea due to bile irritation.

In june 2009 this patient presented with longstanding cholecystitis with two large stones.

Severe local colonic wall thickening with small intramural abscesses reflect the impending fistulisation process.

The patient was treated conservatively and in september 2009 she was symptomfree.

One of the stones and the pus had evacuated to the colon.

Two years later, also the second stone did evacuate subclinically.

A persistent open fistulous tract between gallbladder and right colon was demonstrated on CT and at ERCP.

On CT the tract is seen (yellow arrow) and there is air in the galbladder.

On ERCP the contrast is injected in the bile ducts and fills the gallbladder through the cystic duct and finally also the right colon.