Small Bowel Tumors

Rinze Reinhard and Gerdien Kramer

Radiology department of the VU medical centre, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

Small bowel tumours are rare, accounting for 3-6% of gastrointestinal tumors.

The clinical presentation is non-specific.

Symptoms include anemia, gastro-intestinal bleeding, abdominal pain or small bowel obstruction.

In this article we will focus on the four most common small bowel malignancies:

- Adenocarcinoma

- Lymphoma

- Carcinoid

- GIST

The differential diagnosis will be discussed.

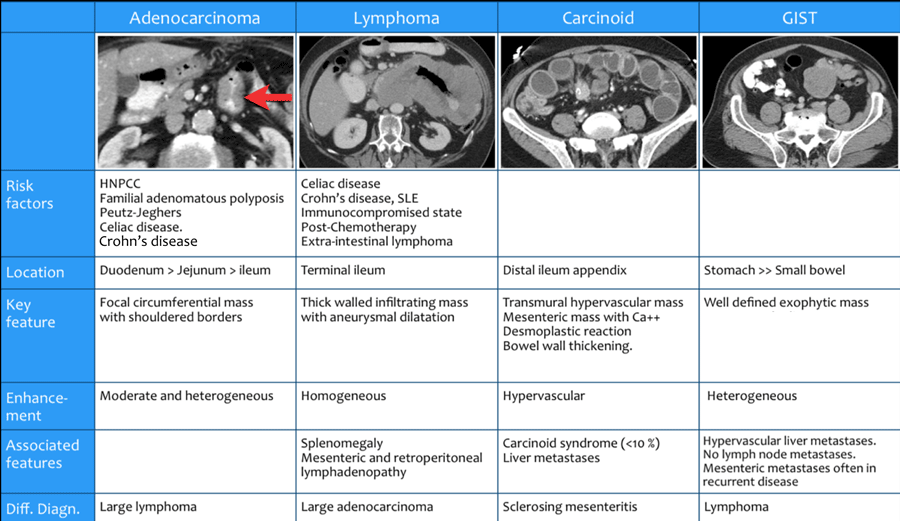

Overview

The table shows the features of the most common malignant small bowel tumors.

Click on the table to enlarge the image.

- HNPCC

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or Lynch syndrome. It is an autosomal dominant genetic condition that has a high risk of gastrointestinal tumors. - Familial adenomatous polyposis

FAP is an inherited condition in which numerous adenomatous polyps form. - MEN-1 syndrome

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 or Wermer's syndrome is a syndrome in which endocrine tumors can develop including carcinoid.

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma represents 25-40% of all small bowel neoplasms.

However coloncarcinoma is 50 times more common.

50% of small bowel adenocarcinomas occur in the duodenum and most of these are found with endoscopy.

The jejunum is the second most prevalent site.

Risk factors:

- HNPCC - hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer.

- Familial adenomatous polyposis.

- Peutz-Jeghers.

- Celiac disease.

- Crohn's disease - occurrence in the ileum is often related to Crohn's disease.

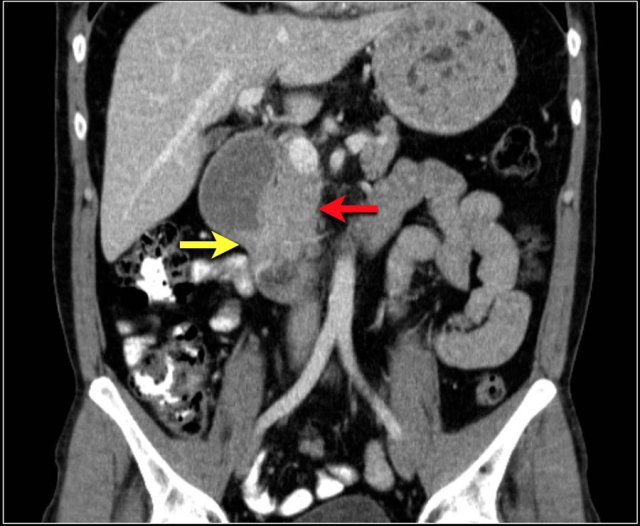

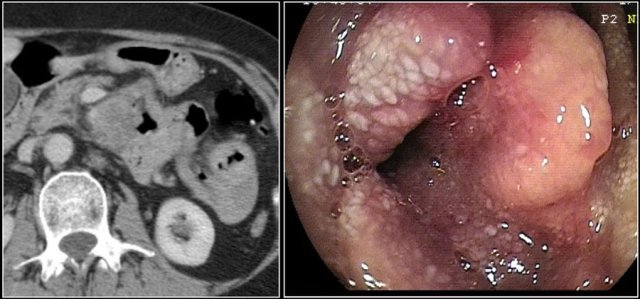

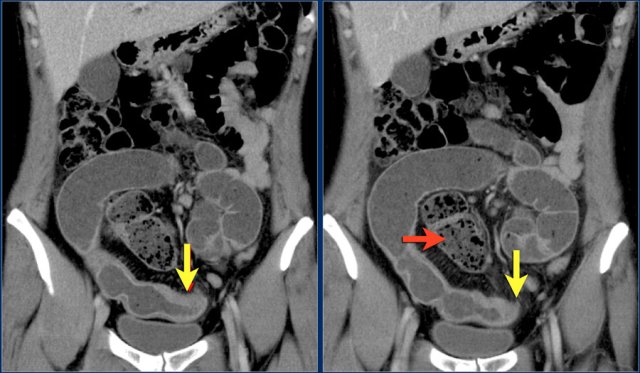

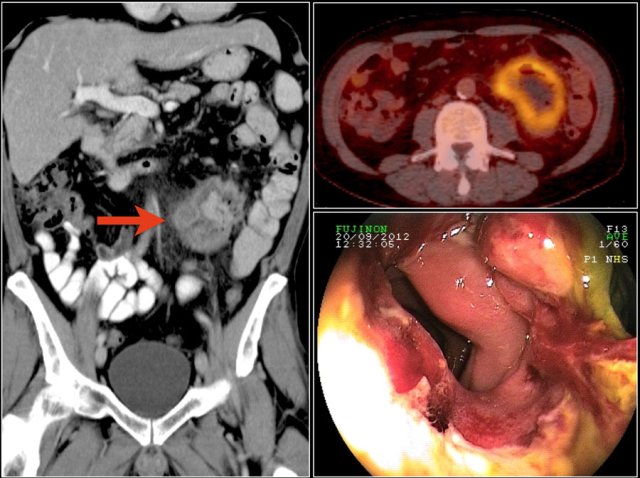

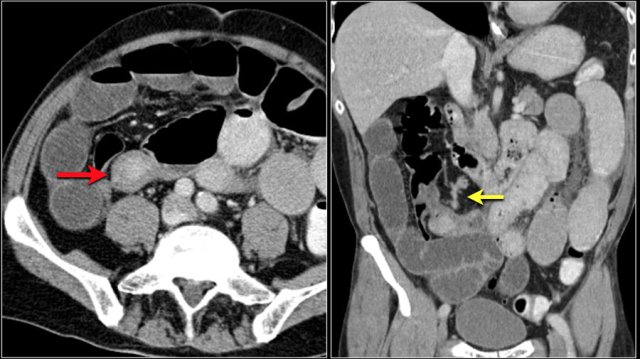

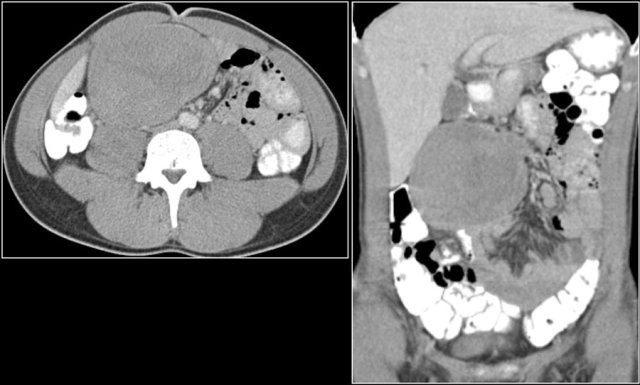

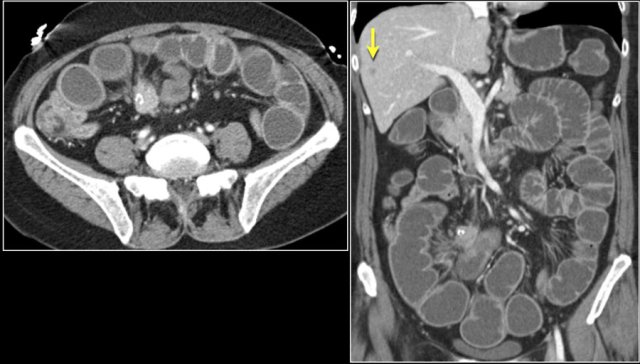

Study the coronal reconstructed CT-image.

Then continue reading.

The findings are:

- Stenotic lesion in the duodenum as a result of an adenocarcinoma (yellow arrow).

- Not possible to separate from the pancreas (red arrow).

- Pre-stenotic dilatation of the duodenum.

The typical imaging representation of a small bowel adenocarcinoma is a focal unilocular, circumferential mass with shouldering of the margins and obstruction.

Less frequently adenocarcinomas present as an intraluminal polypoid mass, which can lead to intussusception.

Ulceration is a quite common feature.

Extraluminal infiltration can present as fatstranding.

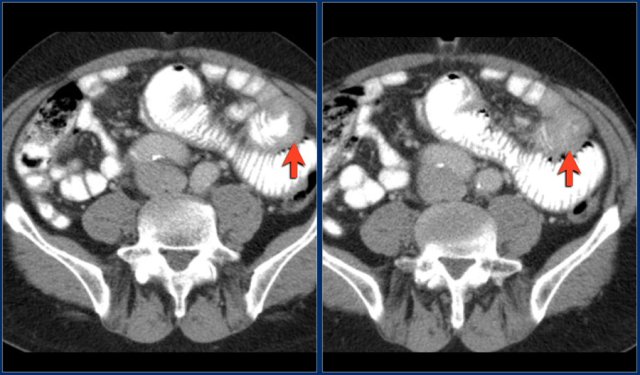

Here another example of a duodenal carcinoma presenting as irregular wall thickening in the distal duodenum (arrows).

Adenocarcinomas often show moderate enhancement, while carcinoid tumors show bright enhancement.

Metastases to the liver and peritoneum occur frequently.

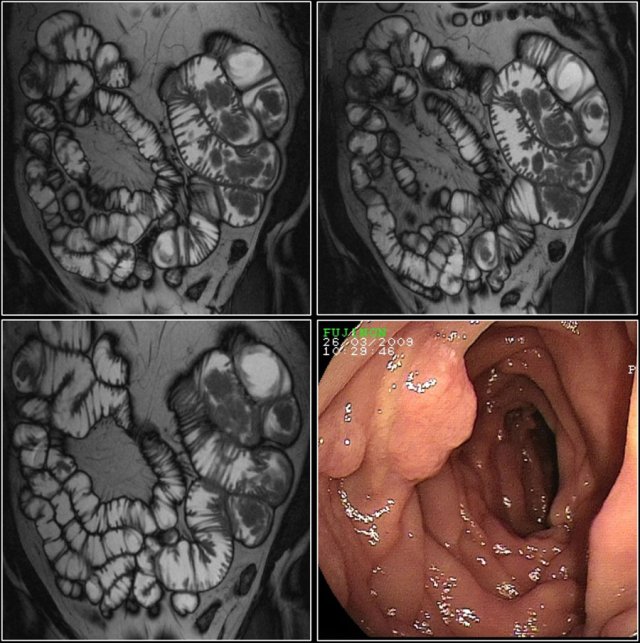

The images show a circumferential mass with shouldering of the margins.

Large adenocarcinomas can mimic a lymphoma as in this case.

The images show an irregular mass in the proximal jejunum.

Although it is a large circumferential growing mass, the lumen is not obstructed.

There is a large conglomerate of hypodense lymph nodes in the adjacent mesentery, consistent with necrotic lumph node metastases (lower image).

This proved to be an adenocarcinoma, but these findings could very well represent a lymphoma.

Here the endoscopic image of the tumor.

Here a patient with extensive wall thickening of the proximal jejunum with aneurysmatic dilatation.

On top of our differential diagnostic list would be a lymphoma, but this proved to be an adenocarcinoma.

Features that favour adenocarcinoma are fat stranding due to mesenteric fat infiltration and lymph node metastases.

In lymphoma fat stranding is uncommon, but lymph node metastases do occur and are usually more bulky.

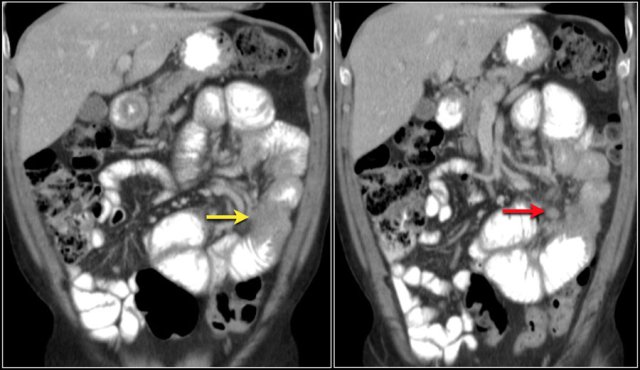

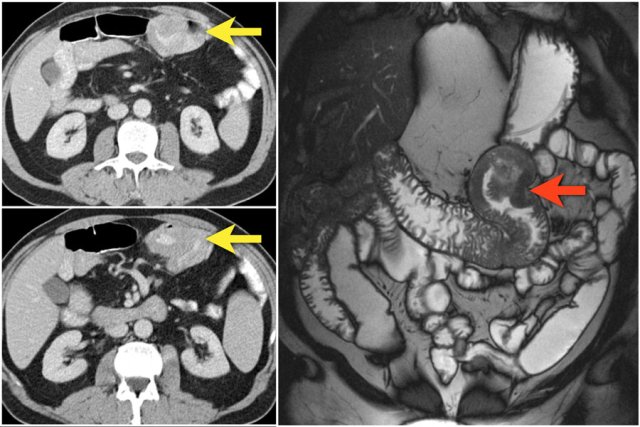

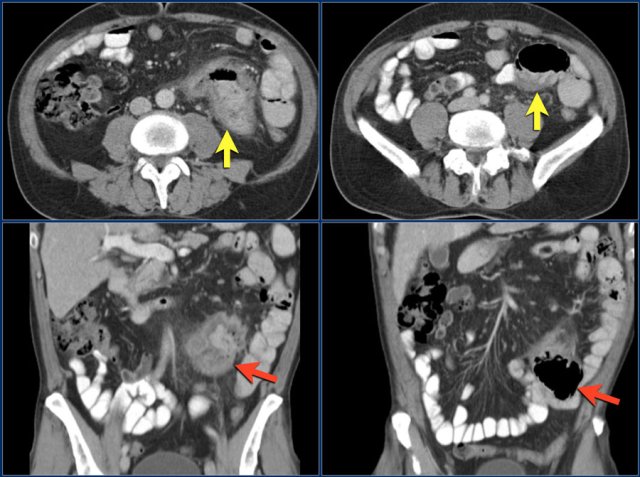

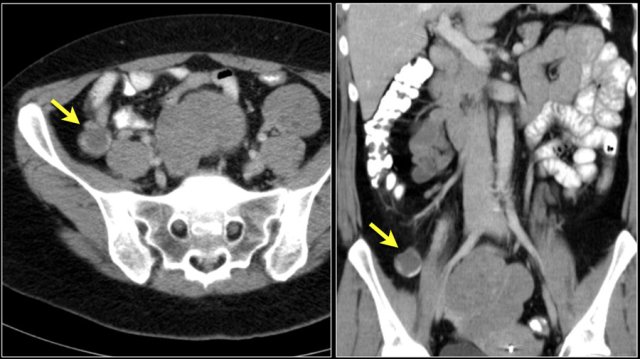

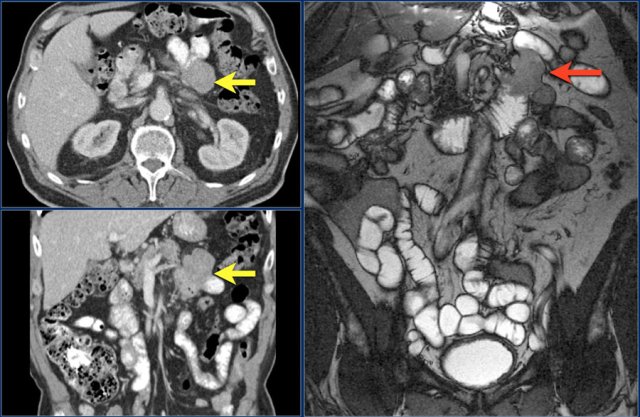

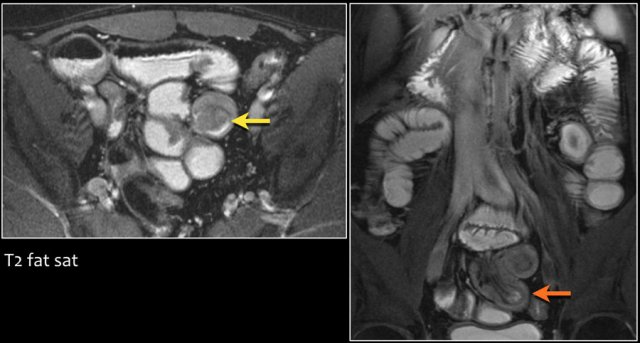

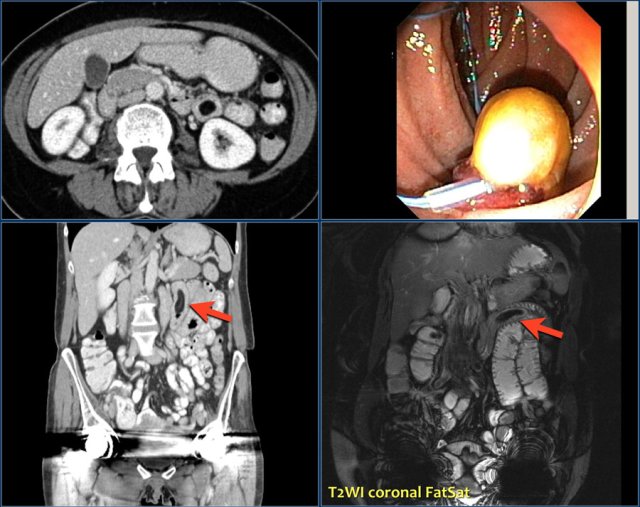

The images show a short obstructing circular mass in the jejunum (yellow arrow) with enlarged lymph node (red arrow).

This proved to be an adenocarcinoma.

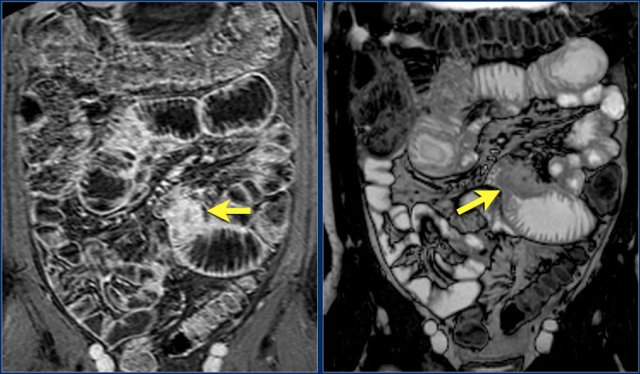

Post-contrast T1W-image with fatsat (left) and T2W-image (right) show an obstructing mass in the jejunum with shouldering (arrow).

There is prestenotic dilatation.

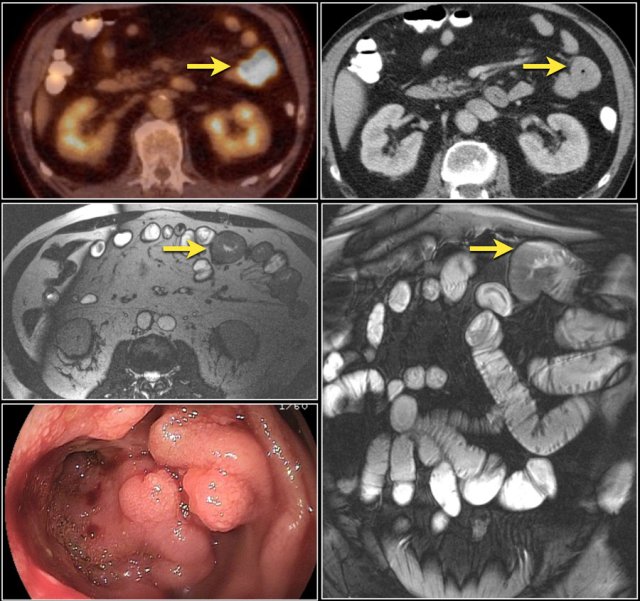

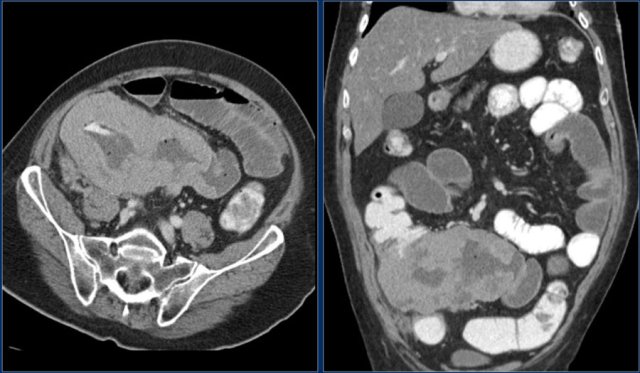

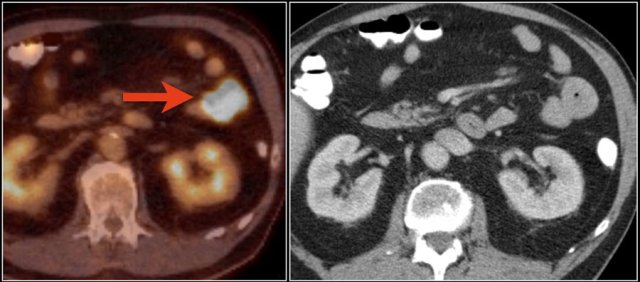

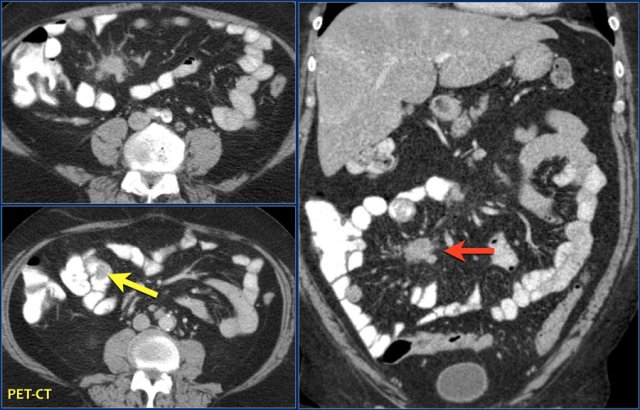

Top images show a circular mass in the proximal jejunum with FDG uptake (yellow arrows).

Lower MR-images show the same jejunal mass with shouldered borders and mesenteric lymphadenopathy (red arrows), consistent with adenocarcinoma.

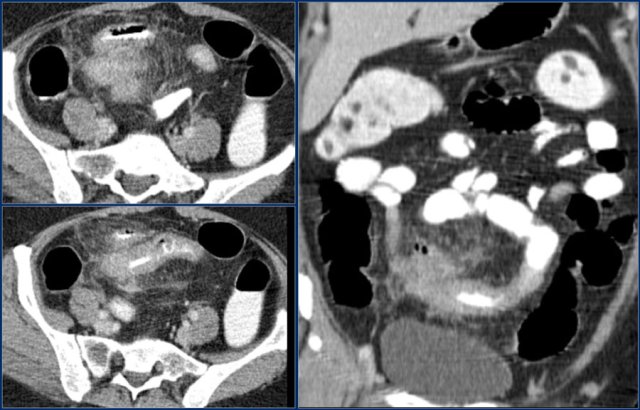

First study the images.

Then continue reading.

The red arrow indicates the sigmoid, which is filled with feces. So this is not a small bowel feces sign.

The findings are:

- Obstructing lesion in the ileum with shouldering leading to small bowel obstruction (yellow arrow).

One could consider the diagnosis of Crohn's disease.

However this patient was not known with Crohn's disease and the terminal ileum (not shown) was normal, which would be uncommon.

At surgery this proved to be an adenocarcinoma.

Here an adenocarcinoma in the proximal jejunum.

The mass is better depicted with MRI than with CT.

As mentioned before 50% of small bowel adenocarcinomas occur in the duodenum.

These tumors are mostly found with endoscopy.

The jejunum is the second most prevalent site.

Occurrence in the ileum is often related to Crohn's disease as in this case.

There is a thickened wall of the ileum with adjacent mesenteric infiltration with foci of extraluminal air indicating perforation.

This proved to be an ulcerating adenocarcinoma in a patient with M. Crohn.

The diagnosis is seldom made pre-operatively due to lack of typical imaging features.

The risk is related to the duration and anatomical extent of the disease and develops in the terminal ileum, in the region of active Crohn's disease.

Here a patient with active Crohn's disease, who has a stenotic segment in the terminal ileum.

This patient does not have an adenocarcinoma.

The findings are:

- Diffuse wall thickening in the distal ileum.

- Comb sign: hypervascularity in the adjacent mesentery.

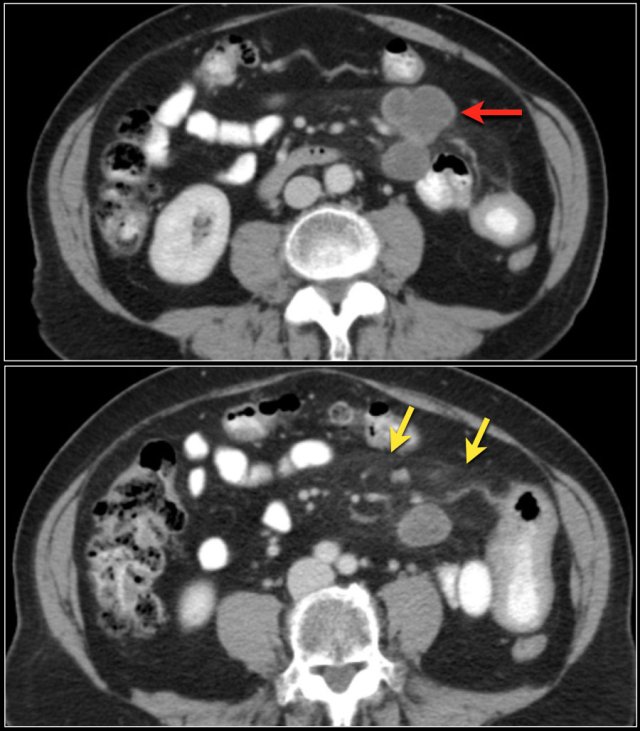

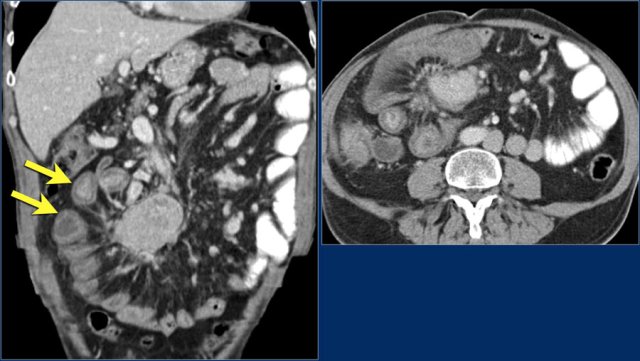

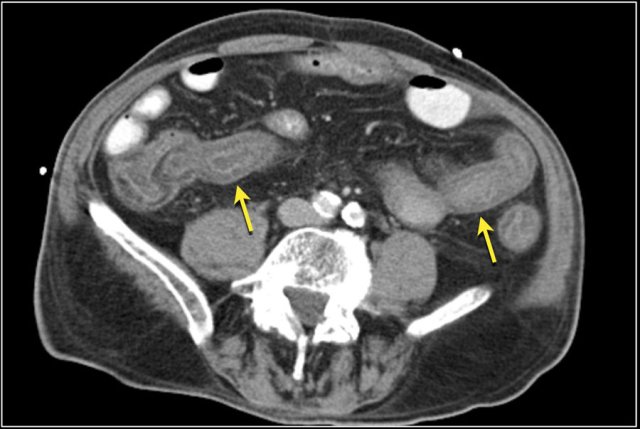

Here another adenocarcinoma located in the jejunum.

There are multiple lymph nodes (red arrow) and there is fat stranding (yellow arrows).

It should not be mistaken for mesenteric panniculitis as these large necrotic lymph nodes are pathologic.

Lymphoma

Lymphomas make up about 20 % of all small bowel tumors.

The distal ileum is the most common site, owing to the large amount of lymphoid tissue that is present in the distal ileum.

Risk factors include celiac disease, Crohn's disease, SLE, immunocompromised state and a history of chemotherapy or extra-intestinal lymphoma.

The typical presentation of a small bowel lymphoma is a thick walled infiltrating mass with aneurysmal dilatation without obstruction.

Aneurysmal dilatation is based upon destruction of the bowel wall and the myenteric nerve plexus.

Here a typical presentation (figure).

There is irregular wall thickening of the terminal ileum with aneurysmatic dilatation.

A less common presentation is as an intraluminal polypoid mass or a large excentric mass with extension into the surrounding soft tissues with possible ulceration and formation of fistulas.

As mentioned before, large adenocarcinomas and lymphomas can have similar imaging appearances.

Bulky mesenteric or retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are findings that support the diagnosis of a lymphoma.

Infiltration of the mesenteric fat favours the diagnosis of an adenocarcinoma.

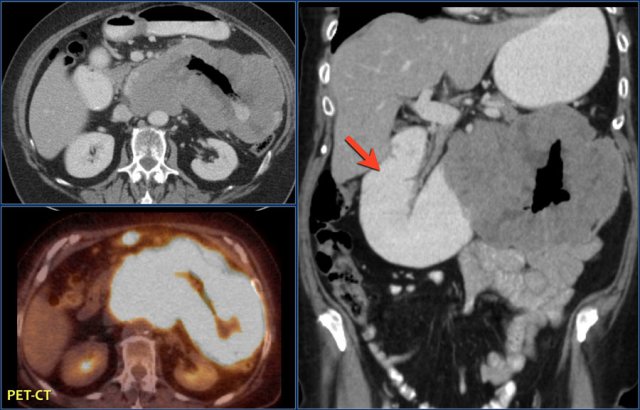

Here a typical lymphoma presenting as a large thick walled mass in the proximal jejunum with FDG uptake.

Dilated lumen at the site of the mass and prestenotic dilatation of the duodenum (red arrow)

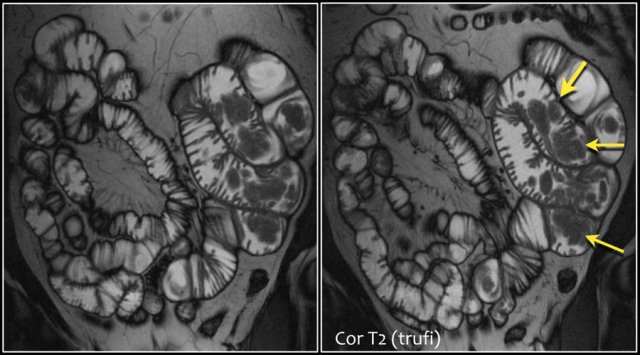

First study the images and take special notice of the first image.

Then continue reading.

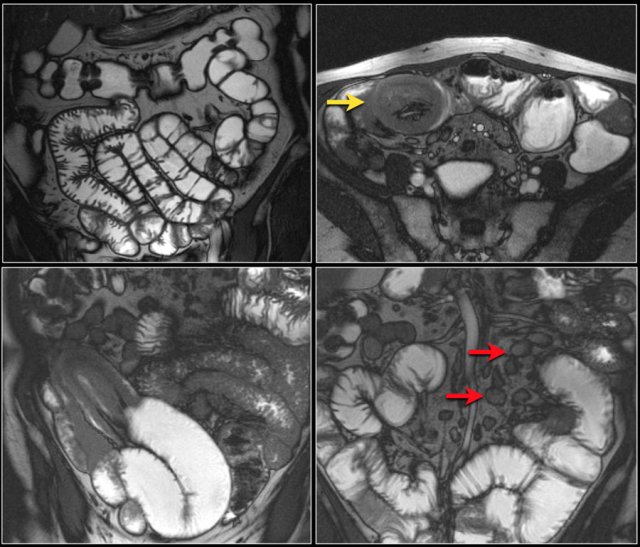

The findings are:

- Reversed fold pattern indicating celiac disease

- Ileal-ileal intussusception (yellow arrow), in a patient with multifocal small bowel lymphoma (not all lesions shown here).

- Mesenteric lymphadenopathy (red arrows).

EATL

Here another patient with celiac disease.

There is an irregular mass in the jejunum with luminal dilatation.

There is infiltration of the mesentery.

Pathology showed a T-cell lymphoma in celiac disease.

This is called enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma or EATL.

This is a type of T-cell lymphoma that affects the small intestine in patients with celiac disease.

Here another example of a T-cell lymphoma in celiac disease.

Carcinoid tumor

Small intraluminal mass in the ileum (yellow arrow). Associated spiculated mesenteric mass with adjacent desmoplastic reaction in small bowel carcinoid.

Small intraluminal mass in the ileum (yellow arrow). Associated spiculated mesenteric mass with adjacent desmoplastic reaction in small bowel carcinoid.

Carcinoid tumors are rare neuroendocrine tumors.

Neuroendocrine tumors of the small can be divided in well-differentiated - also known as carcinoid and poorly differentiated - small or large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Here we will discuss the carcinoid tumors.

Carcinoid tumors constitute 2% of all gastrointestinal tumors.

The incidence of carcinoid tumors increased over the last decades, exceeding that of adenocarcinoma, making it the most common small bowel malignancy.

The most common location of a carcinoid is the appendix, usually as an incidental finding following appendectomy.

It is uncommon to diagnose a carcinoid of the appendix on imaging studies.

These images are of a patient who presented with peritoneal metastases.

The primary tumor proved to be a carcinoid of the appendix.

The second most common location is the distal ileum.

The stomach, colon and rectum are rare locations.

Small bowel carcinoids are multiple in about one third of cases.

There is an association with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN I).

Here a typical carcinoid presenting as a large mesenteric mass with desmoplastic reaction and retraction of adjacent small bowel loops with wall thickening (arrows).

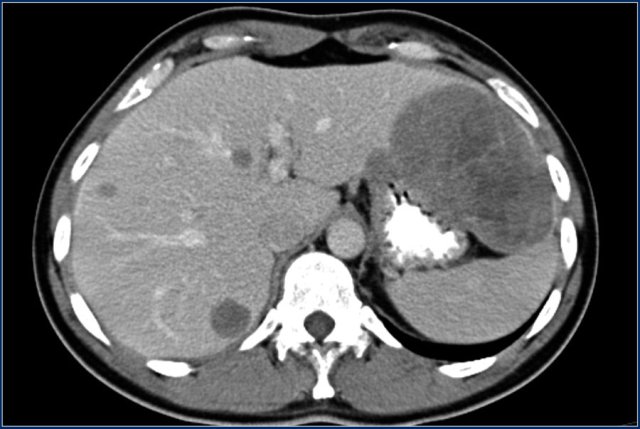

Carcinoid with calcification and desmoplastic reaction. Obstructive small bowel ileus based on intraluminal component of carcinoid. Note small liver metastasis (arrow).

Carcinoid with calcification and desmoplastic reaction. Obstructive small bowel ileus based on intraluminal component of carcinoid. Note small liver metastasis (arrow).

Carcinoid metastases

The likelihood of metastases is related to the size of the tumor.

For example, the incidence of nodal and liver metastases is approximately 20-30% in patients with carcinoid tumors smaller than 1 cm but increases to almost 60-80% for nodal metastases and 20% for liver metastases when tumors are 1-2 cm.

In patients with primary tumors greater than 2 cm, the incidence of nodal metastases is 80% and of liver metastases is 40-50%.

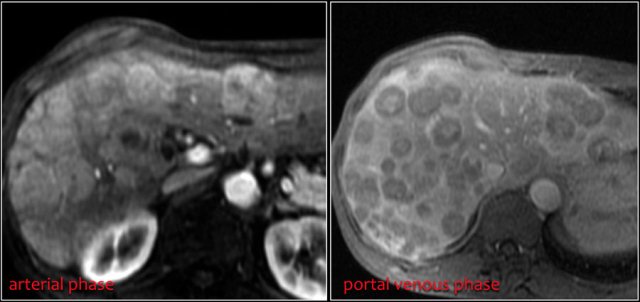

Liver metastases are usually hypervascular and can show central necrosis.

Most of the lymph node metastases show calcifications, similar to the primary tumor.

Same patient.

Four years after the initial CT multiple liver metastases are seen.

Notice hypervascular enhancement pattern in the late arterial phase.

Carcinoid syndrome

The carcinoid syndrome occurs in approximately 5% of carcinoid tumors and becomes manifest when vasoactive substances from the tumors enter the systemic circulation.

It commonly occurs in patients who have liver metastases.

Symptoms include flushing and diarrhea and less frequently bronchospasm and heart failure.

The heart failure is the result of serotonin-induced fibrosis of the cardiac valves, notably the tricuspid and pulmonary valves.

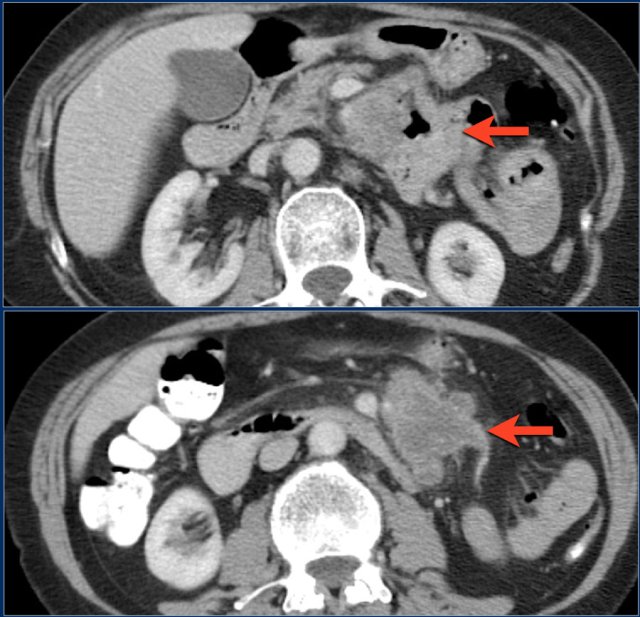

The images show a carcinoid tumor presenting as a hypervascular mass (red arrow) with desmoplastic reaction (yellow arrow).

Carcinoid tumors are slowly growing tumors that may go unrecognized for many years.

They start as small submucosal lesions (images).

As the carcinoid grows, thickening of the bowel wall occurs, leading eventually to extension outside the bowel wall.

Carcinoid tumors can cause an intense desmoplastic reaction with retraction of bowel loops and fibrosis, sometimes leading to bowel ischemia.

However, when the carcinoid is small the findings are non-specific.

It can present as a small submucosal nodule with arterial enhancement (image) and sometimes they lead to intussusception.

GIST

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors are mesenchymal tumors and represent 9% of all small bowel tumors.

These tumors most frequently occur in the stomach, followed by jejunum and ileum.

Occurrence in colon, rectum, esophagus and appendix is rare.

About 20-30 % of GIST's are malignant at presentation.

In the small bowel they are more often malignant than in the stomach.

Tumors smaller than 2 cm are usually benign, whereas masses larger than 5 cm are often malignant.

Malignant GIST's predominantly grow extraluminally and can show necrosis, hemorrhage, calcification (post therapy) and fistula formation.

Typically a GIST is a well defined and exophytic mass with heterogeneous enhancement and a clear delineation from the mesentery.

An intraluminal mass is far less common.

Obstruction is rare because GISTs do not involve the circumferential bowel wall, in contrast to adenocarcinoma.

Unlike carcinoid tumors, the primary lesion in a GIST is large.

Both GIST and lymphoma can show aneurysmal dilation of the bowel.

Liver metastases are usually hypervascular and can be missed on a single portal venous phase CT.

Lymph node metastases are generally not seen.

If lymphadenopathy is seen, you should consider another diagnosis.

Mesenteric or omental metastases are more common in recurrent disease than at first presentation.

This is thought to be due to spill of tumor during surgery.

These metastases can be easily missed, as they often have a low-density center.

After chemotherapy (Imatinib or Gleevec), the liver and mesenteric metastases become hypovascular or even cystic.

Despite radical surgical resection, 40-90 % of patients have recurrence of disease in liver or mesentery.

Gleevec can be given in case of metastatic disease.

Disease recurrence in resected GIST showing hypodense livermetastases and a large heterogeneous peritoneal metastasis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of small bowel tumors includes many infectious and inflammatory diseases, that all present with focal bowel wall thickening.

The most common small bowel tumors are metastases, which are more common than primary malignancies.

Metastases

The spread of metastases to the small bowel can be intraperitoneal, hematogenous, lymphatic or by direct extension.

Most common (50%) is intraperitoneal seeding.

This is mostly seen in primary tumors originating from ovary, appendix and colon.

Metastatic cells implant on the mesenteric border of the bowel.

Hematogenous metastases usually occur in breast carcinoma, melanoma and renal cell carcinoma.

They can be polypoid and can cause intussusception.

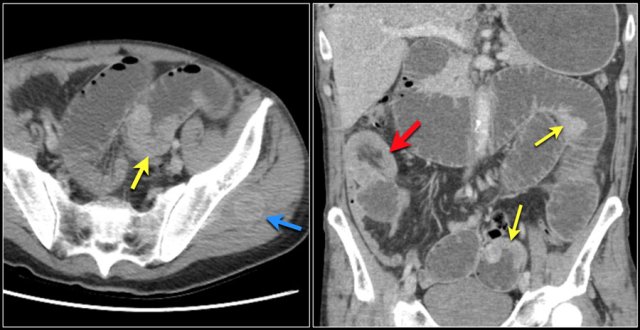

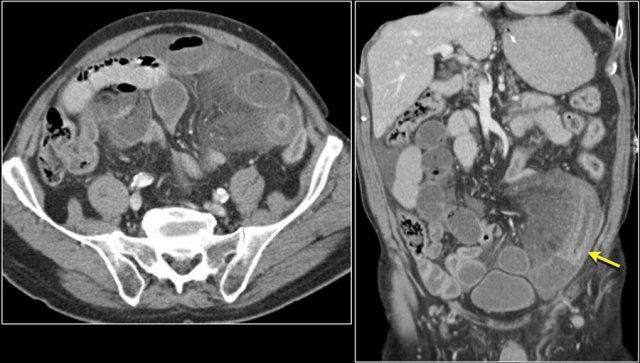

Here a patient with metastatic melanoma.

Left image shows ileal-ileal intussusception due to metastasis.

Right image shows intussusception in coronal plane as well as an enlarged mesenteric lymph node (yellow arrow) and extensive liver metastases.

Another patient with a small bowel metastasis.

This patient had a history of colon- and esophaguscarcinoma.

This patient has multiple intraluminal small bowel masses (yellow arrows), which appeared to be metastases from an unknown primary.

Also note the intussusception (red arrow) en soft tissue metastasis in the left gluteus muscle (blue arrow).

History of ileocecal resection. Focal ileal wall thickening with some enhancement in Crohn's disease.

History of ileocecal resection. Focal ileal wall thickening with some enhancement in Crohn's disease.

Crohn's disease

Wall thickening in inflammatory or infectious small bowel disease should be differentiated from malignant wall thickening. Distinguishing features of inflammation (Crohn's disease) are ulcerations, increased mesenteric vessels (comb sign), skip lesions and increased surrounding fat (creeping fat).

An association between Crohn's disease and small bowel adenocarcinoma is well-established.

Differentiating these two is challenging pre-operatively when there are no typical imaging features.

An indicator of malignancy is a small bowel obstruction that is refractory to medical therapy.

Crohn's disease with multiple lesions (arrows).

Active Crohn's disease.

Long segment of ileal wall thickening with comb sign and transmural enhancement.

Sclerosing or fibrosing mesenteritis

Sclerosing or fibrosing mesenteritis develops in the mesentery and can be mass-like and mimic a malignant tumor like a carcinoid.

In these cases sclerosing mesenteritis can be differentiated by the 'fat ring sign',which means there is preservation of fat surrounding the mesenteric vessels.

Desmoid

Desmoid is a rare, benign, locally aggressive mass composed of fibrous tissue.

It is the most common primary tumor of the mesentery and can mimic a malignant bowel- or mesenteric neoplasm.

Most desmoids are sporadic tumors, but some occur in the setting of Gardner syndrome.

There is often a history of previous abdominal surgery.

Desmoid tumors do not metastasize, but do tend to recur.

The high recurrence rate favors the use of nonsurgical therapy.

Mesenteric desmoids usually show minimal enhancement.

Small bowel or mesenteric vessels can be displaced or encased.

Because these tumors can be very hard, percutaneous biopsy can be challenging.

Adenomas

Adenomas are pre-cancerous lesions that can present as polypoid pedunculated masses on a stalk, a sessile mass (no stalk) or a mural based nodule within the mucosa.

Lesions show homogeneous enhancement and are usually nonobstructive.

Extraserosal extension is suggestive of malignant degeneration.

Here a patient with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with multiple small bowel polyps, mainly located in jejunum.

Polyposis syndromes

Intestinal polyposis syndromes can be divided into the broad categories of familial adenomatous polyposis (like Gardner syndrome), hamartomatous polyposis syndromes (like Peutz-Jeghers syndrome) and other rare polyposis syndromes.

Patients with these syndromes often have multiple small bowel polyps.

Larger polyps can become malignant and can mimic primary small bowel neoplasms.

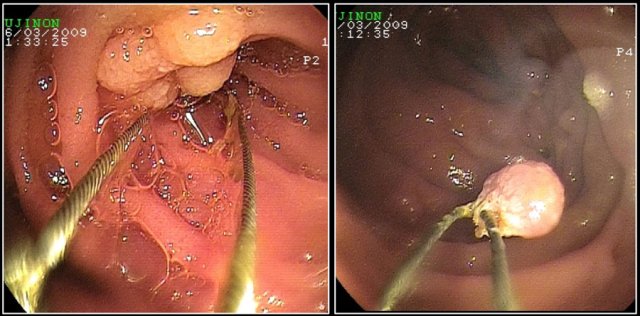

Here a patient with Peutz-Jeghers, who has multiple polyps in the jejunum.

The largest polyp in this patient was removed endoscopically.

PA proven hemangioma: coronal T1 FS post contrast and coronal T2 show enhancing well defined intraluminal jejunal mass..

PA proven hemangioma: coronal T1 FS post contrast and coronal T2 show enhancing well defined intraluminal jejunal mass..

Hemangioma

Most intestinal hemangiomas are located in the jejunum.

They can be sessile or pedunculated and they usually show nodular arterial enhancement and homogeneous enhancement in the delayed phase.

Leiomyoma

Leiomyomas are rare mesenchymal benign tumors.

The origin may be intraluminal, submucosal or extraluminal.

Benign imaging features include sharp margins, homogeneous aspect and homogeneous enhancement.

Lipomas

These are well-circumscribed intraluminal masses with fat attenuation.

Liposarcoma of the small bowel is extremely rare.

CT shows a lesion with fat attenuation at duodenal-jejunal junction.

Low signal intensity of the mass on MR T2 fatsat (right lower image).

Endoscopic view of lipoma (right upper image).

Mesenteric ischemia

Target sign due to ischemic small bowel segment.

Note mesenteric edema and ascites.

Target sign

A target sign is a result of submucosal edema surrounded by enhancing mucosa and muscularis.

It is a benign sign and is usually due to inflammation, ischemia or radiation enteritis.

Typhlitis

Target sign in a patient with neutropenic sepsis, consistent with enterocolitis.

Neutropenic enterocolitis is a life-threatening, necrotizing enterocolitis and occurs most commonly in individuals with hematologic malignancies who are neutropenic and have breakdown of gut mucosal integrity as a result of cytotoxic chemotherapy (8).

"Typhlitis" (from the Greek word "typhlon," or cecum) describes neutropenic enterocolitis of the ileocecal region; we prefer the more inclusive term, "neutropenic enterocolitis," since other parts of the smalland/or large intestine are often involved (8).

Technique

Small bowel tumors can be detected on standard abdominal CT in patients with non-specific symptoms

However if the CT findings are unclear or if a small bowel tumor is suspected clinically, CT-enterography or MRI-enterography or enteroclysis is performed.

Both MRI and CT have good performance for the diagnosis of small bowel tumors.

The choice mainly depends on personal preferences.

We prefer MRI enteroclysis as tumors are often well depicted in the dilated bowel loops without use of radiation.

For MR enterography and enteroclysis fluid (water or methylcellulose) is the enteric contrast media with low signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images.

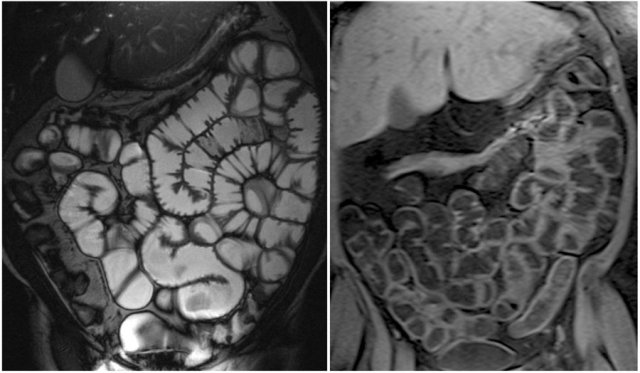

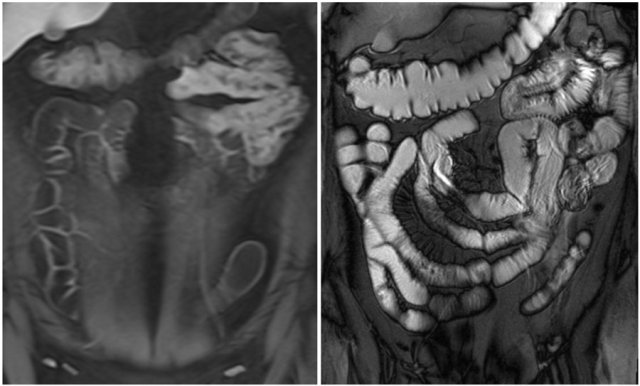

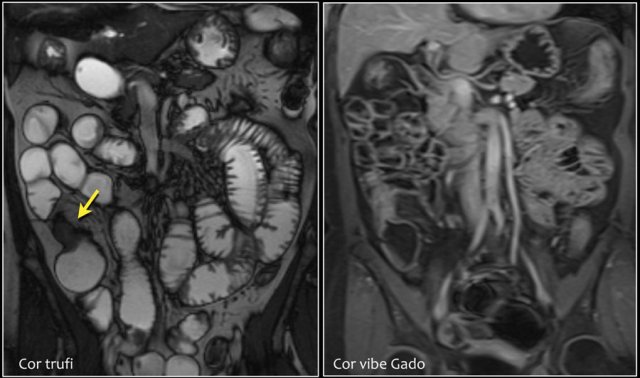

Here we see a coronal T2W-image and a coronal T1W-image with fatsat.

Notice that the small bowel is well distended.

Luminal distension should be ≥ 2 cm.

Bowel wall thickness > 3 mm is considered abnormal.

Collapsed small bowel loops can be easily misinterpreted as wall thickening or abnormal enhancement.

On the coronal T1W-image the jejunal loops are collapsed.

As a result it looks as if there is bowel wall thickening and prominant enhancement.

On the T2W-image during the same examination there is normal distention.

PET-CT is not first choice, but can be useful if findings on CT or MR are equivocal or to look for metastatic disease.