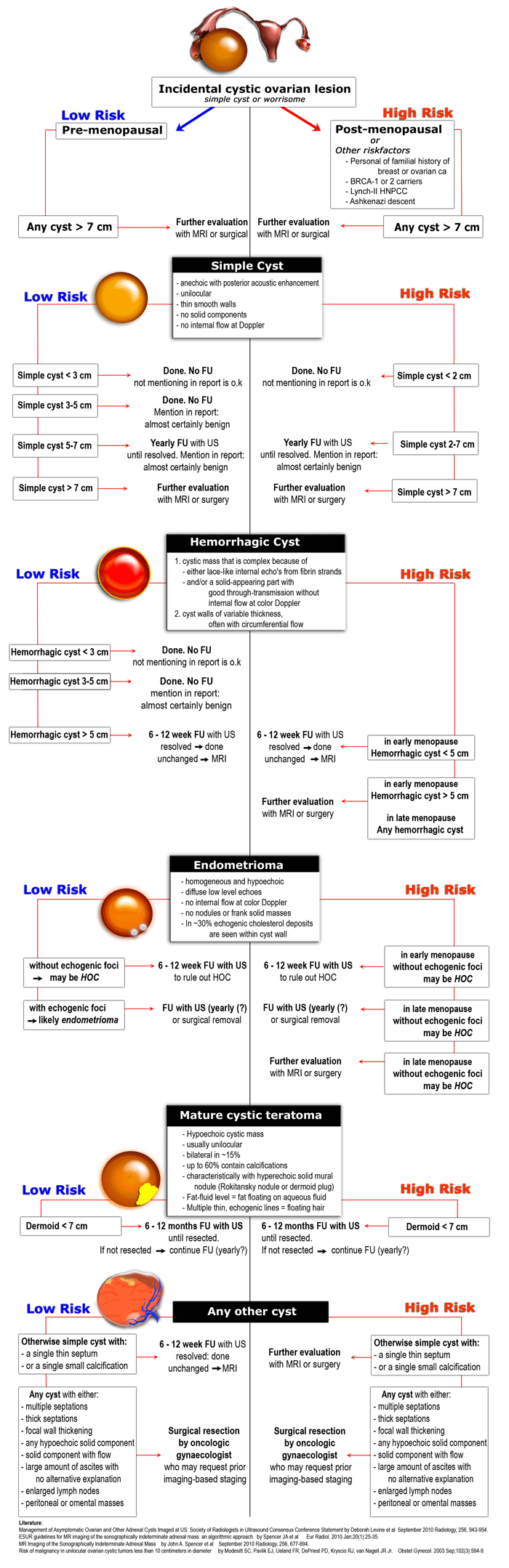

Roadmap to evaluate ovarian cysts.

Wouter Veldhuis, Robin Smithuis, Oguz Akin and Hedvig Hricak

Department of Radiology of the University Medical Center of Utrecht, of the Rijnland hospital in Leiderdorp, the Netherlands and the Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA

Publicationdate

Ovarian cancer is the second most common of all gynecologic malignancies. It is the leading cause of death in this category of diseases, frequently presenting as a complex cystic mass.

The finding of an adnexal cyst causes considerable anxiety in women due to the fear of malignancy. However, the vast majority of adnexal cysts - even in postmenopausal women - are benign.

In this article we will focus on specific features of ovarian cysts that are helpful in making a differential diagnosis. We will present a roadmap for the diagnostic work-up and management of ovarian cystic masses, based on ultrasound and MRI findings.

In Ovarian Cystic Masses II the imaging features of normal ovaries and the most common ovarian cystic masses will be presented, as well as several less common cystic lesions.

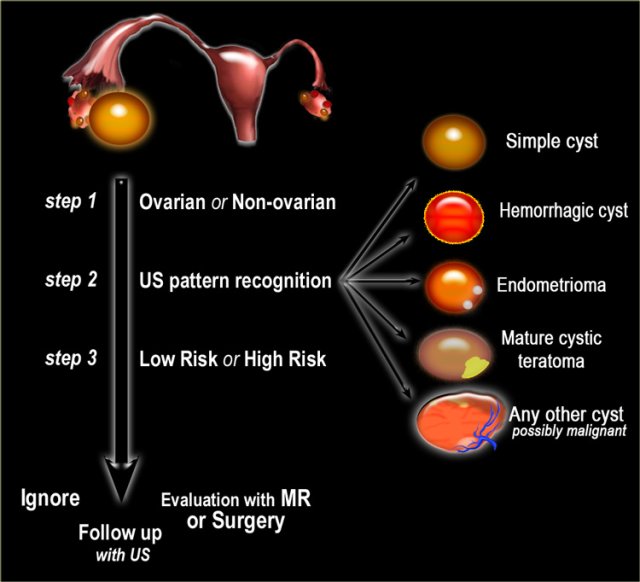

Diagnostic work-up

- Step 1

If a cystic pelvic mass is present, the first step is to find out if it is ovarian or non-ovarian in origin. - Step 2

The next step is to determine if the lesion can be categorized as one of the common, benign ovarian masses (simple cyst, hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma or mature cystic teratoma), or is indeterminate. - Step 3

To aid in selecting the proper work-up, the final step is to determine whether a patient falls into a low-risk category (i.e. premenopausal women without additional risk factors) or a high-risk category (i.e. post-menopausal or premenopausal with additional risk factors).

Based on these steps we can determine further management: ignore, follow-up with US, further evaluation with MRI or excision.

Role of imaging

Role of Ultrasound

For characterization of ovarian masses, ultrasound is often the first-line method of choice, especially for distinguishing cystic from complex cystic-solid and solid lesions.

Role of CT

CT is useful for the N- and M-staging of proven malignant lesions.

Role of MRI

For complex lesions, primary evaluation with ultrasound is often followed by further evaluation with MRI.

Even with MRI it is often not possible to make an accurate diagnosis of neoplastic subtype.

By using MRI as an adjunct to sonography a delay in the treatment of potentially malignant ovarian lesions is prevented.

This is not only beneficial to the small number of women who do have ovarian cancer, but also a proven cost-effective approach to the management of sonographically indeterminate adnexal lesions.

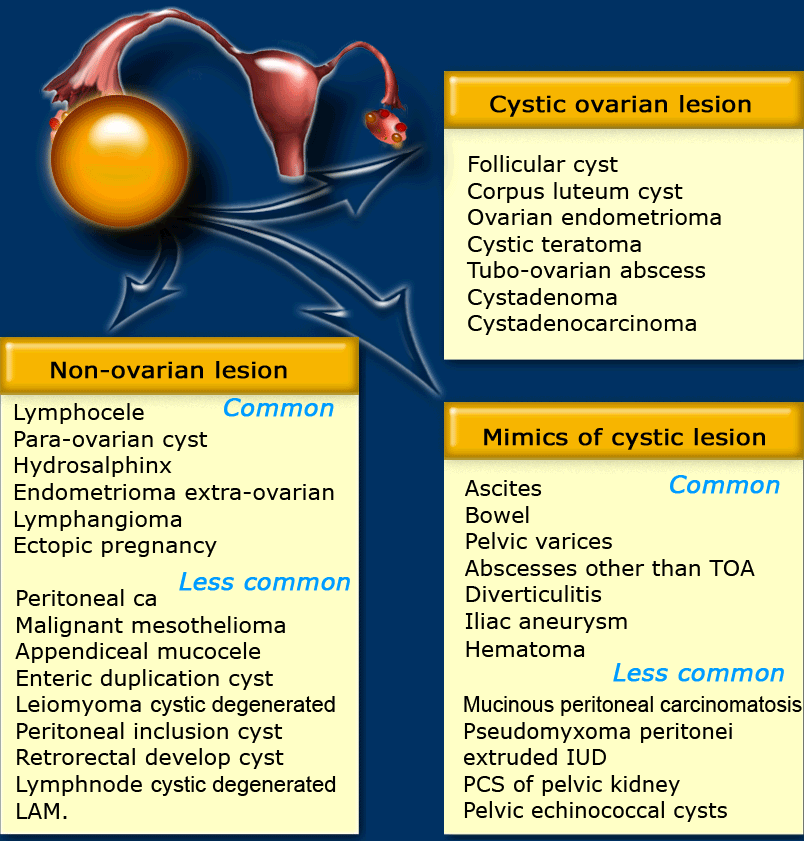

Ovarian or non-ovarian

If a cystic adnexal mass is present and you suspect an ovarian origin, the first thing to do is try to identify the ovaries.

If the gonadal vessels lead to the lesion with no separately identifiable normal ovaries, then most likely you are dealing with an ovarian lesion.

If both ovaries are separately identifiable from the lesion, you are dealing with a non-ovarian cystic lesion, or a lesion that mimics a cystic mass.

The next step would be to check if there is uni- or bilateral disease and to look for any solid components that may indicate malignancy.

Also look for secondary findings like ascites, enlarged lymph nodes and peritoneal deposits.

The table shows a differential diagnosis for possible cystic ovarian masses.

A helpful tool to identify the ovaries is to follow the ovarian veins caudally.

Scroll through the CT-images and follow the right ovarian vein from where it joins the inferior vena cava, and the left ovarian vein where it joins the left renal vein, until you identify the ovaries.

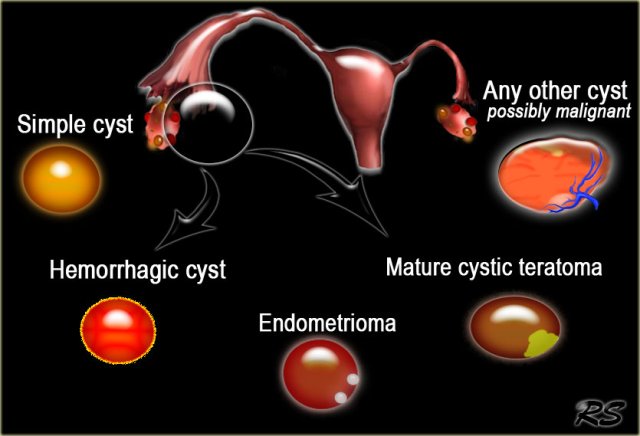

Ultrasound pattern recognition

Pattern recognition on ultrasound often allows a fairly confident diagnosis of common cystic ovarian masses.

This means that in many cases the diagnostic work-up is based on determining the probability that we are dealing with a lesion which falls into the category of a simple cyst, hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma or a mature cystic teratoma (commonly referred to as a dermoid cyst).

Most other cystic lesions are indeterminate and therefore possibly malignant. These therefore require further evaluation, either with MRI or surgical excision.

Simple cyst

US findings that allow a confident diagnosis of a simple ovarian cyst are:

- Anechoic lesion with posterior acoustic enhancement

- Unilocular

- Thin, smooth walls

- No solid or well-vascularized components

The US-image shows two simple cysts in the right ovary with ovarian stroma in between.

The surrounding vessels are normal and there are no vascularized septations.

These were simple follicular cysts in a premenopausal woman.

Differential diagnosis

Most simple cysts are functional cysts, usually follicular cysts.

They are commonly seen in premenopausal women, but functional cysts also still do occur in postmenopausal women.

Some simple cysts may turn out to be paraovarian or paratubal cysts.

A hydrosalpinx may also mimic an ovarian cyst.

Cystadenomas can also present as simple cysts, but they usually present as a large cyst in a postmenopausal woman.

In a large cancer screening study from 1987 to 2002 including 15,106 women of 50 years or older, 2763 women (18%) were diagnosed with a unilocular ovarian cyst.

None of these isolated unilocular cysts turned out to be ovarian cancer (4).

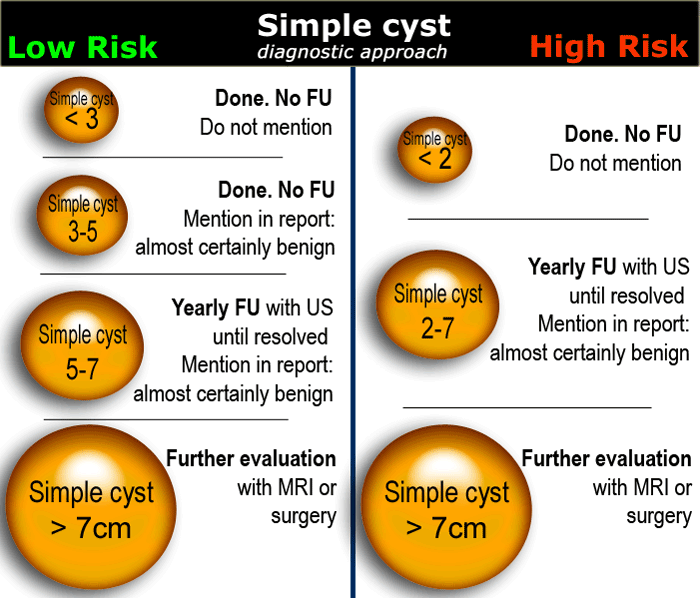

In women of reproductive age, cysts up to 3 cm are a normal physiologic finding.

These simple physiologic cysts do not need to be described in the imaging report and do not require follow-up (1).

Cysts up to 7 cm in both pre- and postmenopausal woman are almost certainly benign.

Cysts larger than 7 cm may be difficult to assess completely with US and therefore further imaging with MR or surgical evaluation should be considered.

Hemorrhagic ovarian cyst - HOC

When a Graafian follicle or follicular cyst bleeds, a complex hemorrhagic ovarian cyst (HOC) is formed.

US findings that allow a confident diagnosis of a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst are:

- Low risk patient

- Cystic mass The cyst may contain a solid-appearing area with good through-transmission, without internal flow at color Doppler, and typically with concave margins, consistent with a blood clot

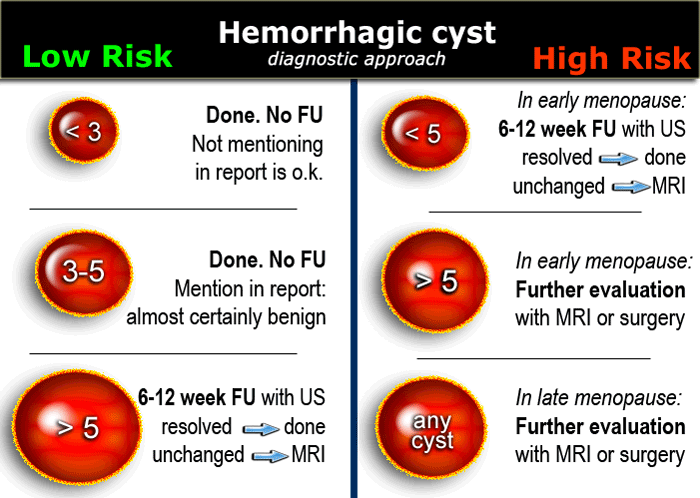

In premenopausal women short term follow-up is recommended in hemorrhagic cysts > 5 cm.

The same follow-up is recommended in early postmenopausal women who have a cyst with all the characteristics of a HOC

Larger hemorrhagic cysts in the early menopause and any hemorrhagic cyst in the late menopause should be considered possibly neoplastic and MRI or surgical evaluation should be considered.

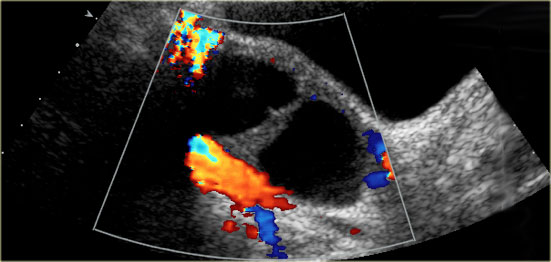

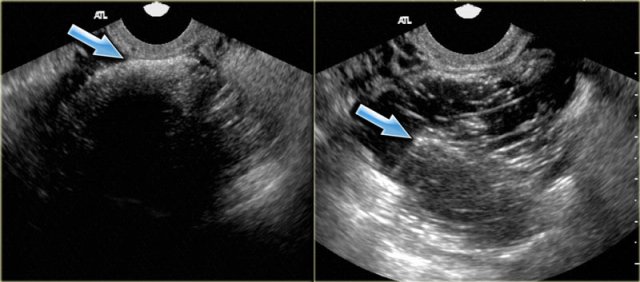

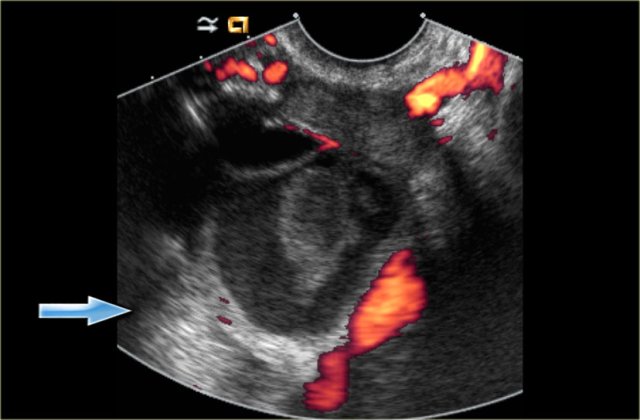

Hemorrhagic cyst with a clot mimicking a neoplasm. Notice absence of flow and good through-transmission (arrow)

Hemorrhagic cyst with a clot mimicking a neoplasm. Notice absence of flow and good through-transmission (arrow)

Differential diagnosis

When hemorrhagic cysts present with diffuse low-level echoes, their appearance can be similar to that of endometriomas.

In the acute phase a hemorrhagic cyst may be completely filled with low-level echoes, simulating a solid mass (5).

Clot in a hemorrhagic cyst may occasionally mimic a solid nodule in a neoplasm. Clot, however, often has concave borders due to retraction, while a true mural nodule has outwardly convex borders.

In both cases there will be no internal flow at Doppler US and there will be good through-transmission.

Hemorrhagic cysts typically resolve within 8 weeks.

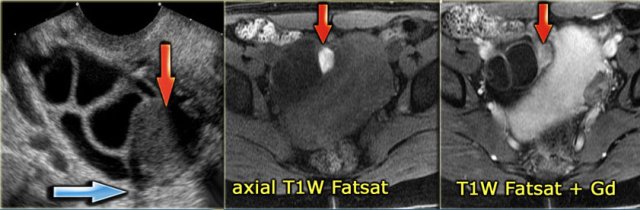

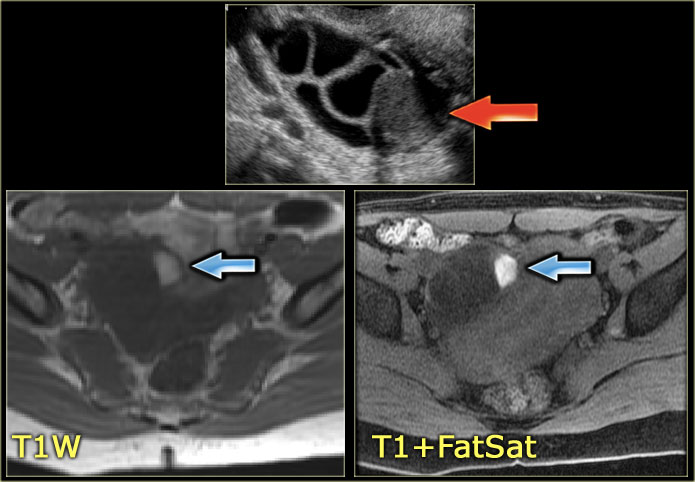

The ultrasound image shows multiple simple and one complex right ovarian cyst, with diffuse low-level echos and absence of flow on Doppler US.

Note that there is good through-transmission, also through the complex cyst (blue arrow).

On the T1 with fatsat the lesion remains bright, ruling out a fatty lesion.

After Gd administration there is no enhancement, confirming that this is a cystic hemorrhagic lesion, most likely a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst, although your differential may include an endometrioma.

Endometrioma

US findings that allow a confident diagnosis of an endometrioma are:

- Homogeneous and hypoechoic mass

- Diffuse low-level echoes (ground-glass)

- No internal flow at color Doppler

- No enhancing nodules or solid masses

- In 30% echogenic foci are seen within cyst wall

In women of any age, probable endometriomas require initial 6-12 week follow-up to rule out a hemorrhagic cyst.

Until surgically removed, endometriomas require follow-up with ultrasound, for example on a yearly basis.

This image from a vaginal ultrasound shows a large hypoechoic, cystic lesion with diffuse low-level echoes and two small echogenic foci.

These have been postulated to be cholesterol deposits, but may also constitute small blood clots or debris.

It is important to differentiate these echogenic foci from true wall nodules.

Finding these echogenic foci makes the diagnosis of an endometrioma very likely.

Mature cystic teratoma

US findings that are characteristic of a mature cystic teratoma are:

- Hypoechoic mass with hyperechoic nodule (Rokitansky nodule or dermoid plug)

- Usually unilocular (90%)

- May contain calcifications (30%)

- May contain hyperechoic lines caused by floating hair

- May contain a fat-fluid level, i.e. fat floating on aqueous fluid

Shown are transvaginal ultrasound images of two patients that demonstrate the 'tip-of-the-iceberg' sign: acoustic shadowing from the hyperechoic part of the dermoid cyst (arrow).

When misinterpreted as bowel gas, the lesion may be overlooked.

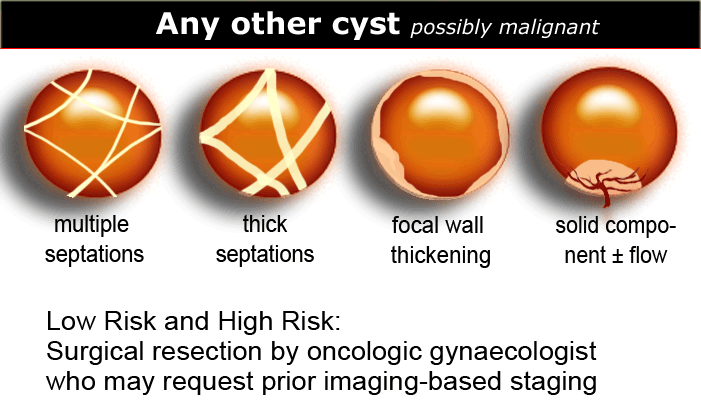

Any other cyst - possible neoplasm

All other cystic lesions are regarded as possibly neoplastic and therefore possibly malignant.

Surgical resection is needed by an oncologic gynaecologist, who may request prior imaging-based staging.

Findings indicating possible neoplasm:

- Large size

While benign lesions can be very large, the likelihood that a lesion is neoplastic increases with size.

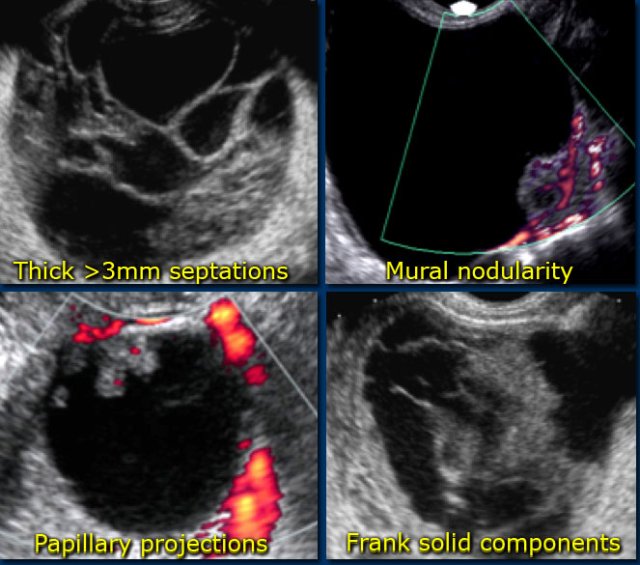

Also the likelihood that a neoplastic lesion is malignant, increases with the size of the lesion. - Vascularized septations

The presence of septations indicates a possible neoplasm. When septations have a thickness of more than 3mm and are well-vascularized - while non-specific - both increase the likelihood that a neoplasm is malignant. - Vascularized solid components

Vascularized nodularities, papillary projections, or frank solid masses all increase the likelihood of a neoplastic nature. - Vascularized thick, irregular wall

Lesions with thin walls are more often benign and lesions with thick, irregular walls are more often malignant. However, there is some overlap, making wall thickness a less useful criterion. For example a corpus luteum cyst may also have a thickened, vascularized wall. - Secondary findings associated with malignant lesions:

Large quantities of ascites, lymphadenopathy and peritoneal deposits are strongly associated with an increased likelihood of malignancy.

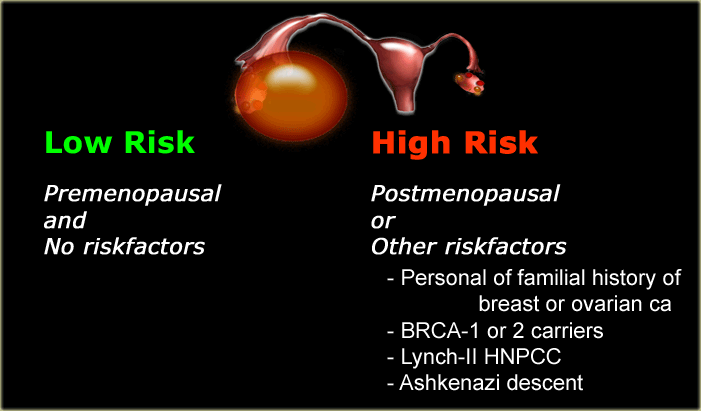

Low-risk or High-risk

Once we have determined a cystic ovarian lesion is either a probable simple cyst, hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma or mature cystic teratoma, or is indeterminate, the next step is to place the patient in a low-risk or high-risk group (table).

The final decision to ignore, follow or excise a cystic ovarian lesion is based on:

- Morphology of the lesion on US, CT or MRI

- Risk group (low versus high)

- Symptomatic lesion versus incidental finding

- Additional findings such as ascites, lymphadenopathy or peritoneal implants

That said, the great majority of cystic ovarian lesions is benign.

While the risk of malignancy does increase with age, even in post-menopausal women the risk of malignancy in a simple ovarian cyst

Although complex ovarian cysts in post-menopausal women are also most often benign, they do require further work-up, because of the chance of malignancy.

'the Roadmap'

The natural history of incidentally detected pelvic masses with benign US morpgology is not known and therefore the optimal management is also unknown.

The roadmap is based on the 2010 Consensus Guidelines published in (1) and (2) and on the findings in (3) and (4).

The mentioned size cut-offs and follow-up frequencies are accepted practices but not ironclad rules.

Local guidelines may differ based on the clinical scenario and institutional practice preferences.

Many of the imaging criteria described in this article are the same for ultrasound, CT and MRI, although of course not every feature is equally detectable on all modalities.

Risk factors

Age is the most important risk factor for all women.

Lesions in pre-menopausal and post-menopausal women are managed differently.

Several other factors (see table) may place a woman in a higher risk category.

Concordantly, the roadmap shows two pathways, one for lower-risk and one for higher-risk patients.

MRI protocol - which sequences, and why

MRI protocol

There are many possible 'Pelvic/Ovarian mass' protocols.

The basic building blocks are simple and are the same for all protocols:

- High-resolution, T2W sequence without fatsat, in at least 2 planes -> anatomy

- T1W sequence without fatsat, or preferably a T1W opposed-phase sequence -> detection of fat, in teratoma

- T1W sequence with fatsat -> mainly for the identification of blood products and for correlation to post-contrast T1W images

- A Proton-Density or T1W sequence extending to the upper abdomen -> nodal disease. Some institutions may prefer to skip this sequence in favor of a staging CT or PET/CT.

- A T1W sequence with fatsat after administration of Gadolinium -> enhancement of solid lesions or lesion components.

- A diffusion-weighted sequence with a highest b-value of 500- 1000 s/mm2 -> detection (not staging) of lymph nodes and detection of peritoneal deposits.

A very short protocol may consist of only 1, 2 and 3 (e.g., when the request is to 'rule out an ovarian mass').

Many radiologists prefer a slightly more comprehensive protocol including 4, and often 5.

When the clinical setting is characterization or staging of a known ovarian lesion, 4 (or CT) and 5 should always be included.

The role of diffusion-weighted MRI is yet to be determined, but DWI is a useful aid in the detection of lymph nodes, tumors and peritoneal deposits.

For the purpose of detection, the DW images are sometimes fused with (superimposed on) anatomical T2W images.

DWI cannot discriminate benign from metastatic lymph nodes.

Further differences in protocols all arise as variations on this simple theme.

For example:

- T2W images in more than 2 planes, or obliquely angled orthogonal to the anatomic structure of interest, are often useful for cervical or uterine-body pathology. -

- Variations in FOV, with a larger FOV to cover the whole pelvis and a smaller FOV centered on the lesion of interest.

- Post-contrast images in 2 or even 3 planes.

- Sagittal T2W cine acquisition for recording uterine wall contractions.

MR imaging is a valuable adjunct to US, as it allows identification of blood products within hemorrhagic masses that may mimic solid tumor at US.

Fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR images may reveal small amounts of fat, which allows the diagnosis of a mature teratoma ('dermoid').

Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR imaging depicts features of malignancy such as enhancing mural nodules and/or enhancing solid areas with or without necrosis (3).

These MR images show a lesion with high signal on T1.

This indicates either blood, other high protein content or fat.

On the image with fat-saturation there is suppression of the signal.

This means that we are dealing with a fat-containig lesion, i.e. a mature cystic teratoma.

The US image shows an echogenic lesion.

The corresponding lesion has a high signal on the T1-weighted MR image.

This indicates either blood, high protein or fat.

On the image with fat-saturation there is no suppression of the signal.

This means that we are dealing with a blood-containig lesion, i.e. most likely a hemorrhagic cyst.