Dementia - Role of MRI

Frederik Barkhof, Marieke Hazewinkel, Maja Binnewijzend and Robin Smithuis

Alzheimer Centre and Image Analysis Centre, Vrije Universiteit Medical Center, Amsterdam and the Alrijne Hospital, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands

Publicationdate

This presentation will focus on the role of MRI in the diagnosis of dementia and related diseases.

We will discuss the following subjects:

- Systematic assessment of MR in dementia

- MR protocol for dementia

- Typical findings in the most common dementia syndromes

- Alzheimer's disease (AD)

- Vascular Dementia (VaD)

- Frontotemporal lobe dementia (FTLD)

- Short overview of neurodegenerative disorders which may be associated with dementia

Introduction.

The role of neuroimaging in dementia nowadays extends beyond its traditional role of excluding neurosurgical lesions.

Radiological findings may support the diagnosis of specific neurodegenerative disorders and sometimes radiological findings are necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

It is a challenge for neuroimaging to contribute to the early diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease.

Early diagnosis includes recognition of pre-dementia conditions, such as mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

In addition, early diagnosis allows early treatment using currently available therapies or new therapies in the future.

Neuroimaging may also be used to assess disease progression and is adopted in current trials investigating MCI and AD.

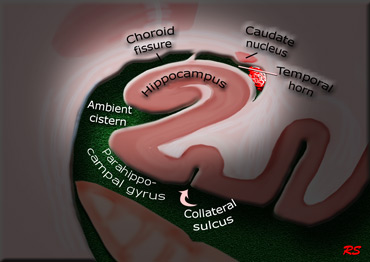

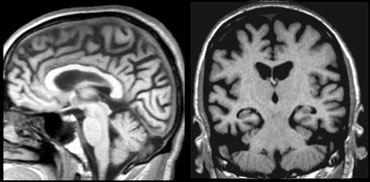

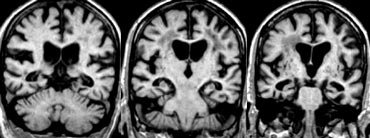

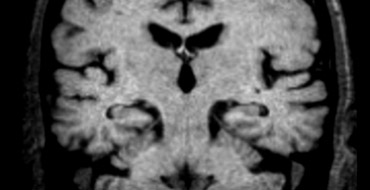

The coronal image shows the hippocampus, the main structure involved in many forms of dementia.

Assessment of MR in Dementia

An MR-study of a patient suspected of having dementia must be assessed in a standardized way.

First of all, treatable diseases like subdural hematomas, tumors and hydrocephalus need to be excluded.

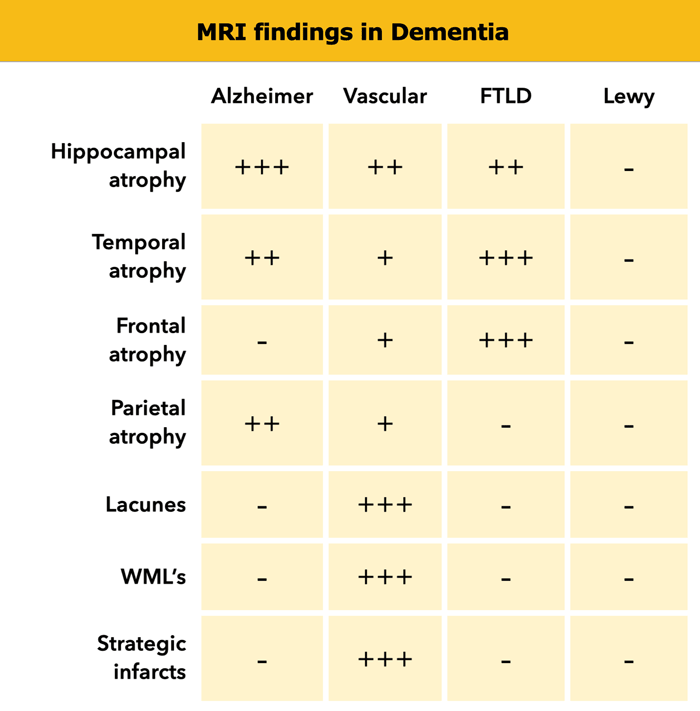

Next we should look for signs of specific dementias such as:

- Alzheimer's disease (AD): medial temporal lobe atrophy (MTA) and parietal atrophy.

- Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (FTLD): (asymmetric) frontal lobe atrophy and atrophy of the temporal pole.

- Vascular Dementia (VaD): global atrophy, diffuse white matter lesions, lacunes and 'strategic infarcts' (infarcts in regions that are involved in cognitive function).

- Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): in contrast to other forms of dementia usually no specific abnormalities.

So when we study the MR images we should score in a systematic way for global atrophy, focal atrophy and for vascular disease (i.e. infarcts, white matter lesions, lacunes).

When we study the MR images we must systematically score for global atrophy, focal atrophy and for vascular disease (i.e. infarcts, white matter lesions, lacunes).

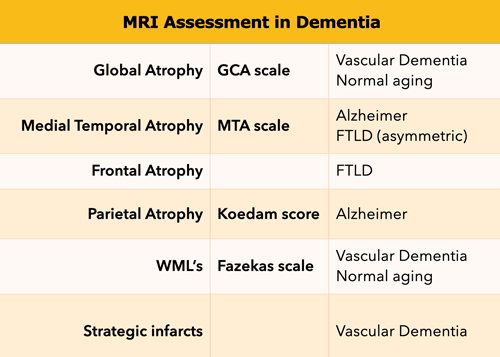

This standardized assessment of the MR findings in a patient suspected of having a cognitive disorder includes:

- GCA-scale for Global Cortical Atrophy

- MTA-scale for Medial Temporal lobe Atrophy

- Koedam score for parietal atrophy

- Fazekas scale for WM lesions

- Looking for strategic infarcts

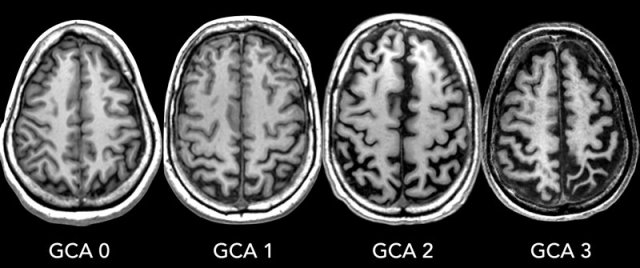

GCA-scale for Global Cortical Atrophy

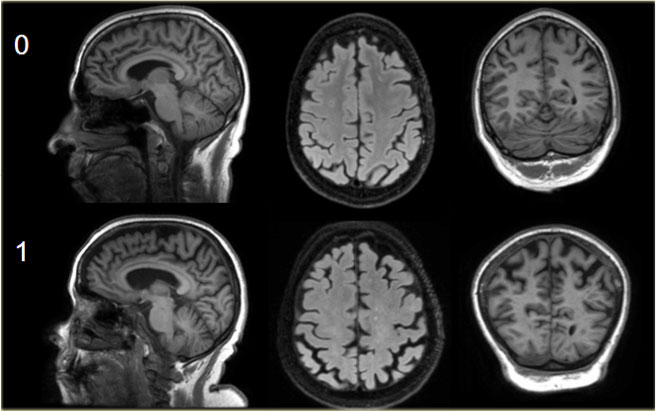

GCA scale is the mean score for cortical atrophy throughout the complete cerebrum:

- 0: no cortical atrophy

- 1: mild atrophy: opening of sulci

- 2: moderate atrophy: volume loss of gyri

- 3: severe end-stage atrophy: 'knife blade'.

Cortical atrophy is best scored on FLAIR images.

In some neurodegenerative disorders the atrophy is asymmetric and occurs in specific regions.

A radiological report should mention any regional atrophy or asymmetry.

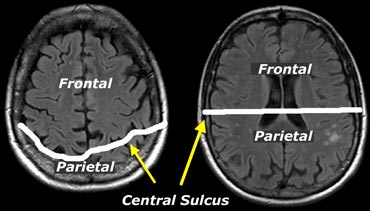

When assessing atrophy in different regions keep in mind that cranially, the central sulcus lies more posteriorly than you would expect (figure).

MTA-scale for Medial Temporal lobe Atrophy

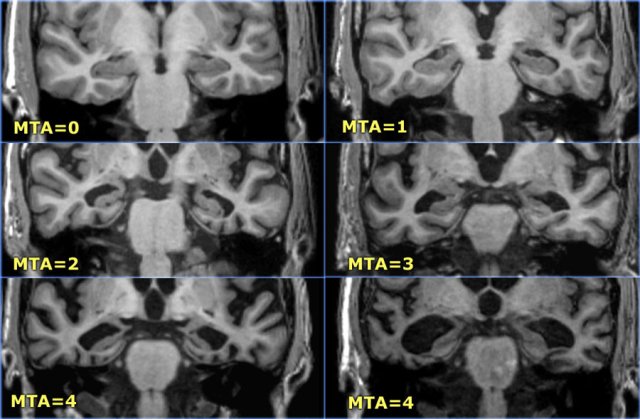

The MTA-score should be rated on coronal T1-weighted images at a consistent slice position.

Select a slice through the corpus of the hippocampus, at the level of the anterior pons.

> 75 years : MTA-score 3 or more is abnormal (i.e. 2 can still be normal at this age)

Data from a study with 222 controls and patients with various forms of dementia in which this visual rating scale was used to assess temporal lobe atrophy suggest that sensitivities and specificities of 85% can be obtained for patients with AD.

The score is based on a visual rating of the width of the choroid fissure, the width of the temporal horn, and the height of the hippocampal formation.

- score 0: no atrophy

- score 1: only widening of choroid fissure

- score 2: also widening of temporal horn of lateral ventricle

- score 3: moderate loss of hippocampal volume (decrease in height)

- score 4: severe volume loss of hippocampus

< 75 years: score 2 or more is abnormal.

> 75 years: score 3 or more is abnormal.

Here you can scroll through the images for examples of MTA score 0-4.

- score 0: no atrophy

- score 1: only widening of choroid fissure

- score 2: also widening of temporal horn of lateral ventricle

- score 3: moderate loss of hippocampal volume (decrease in height)

- score 4: severe volume loss of hippocampus

< 75 years: score 2 or more is abnormal.

> 75 years: score 3 or more is abnormal.

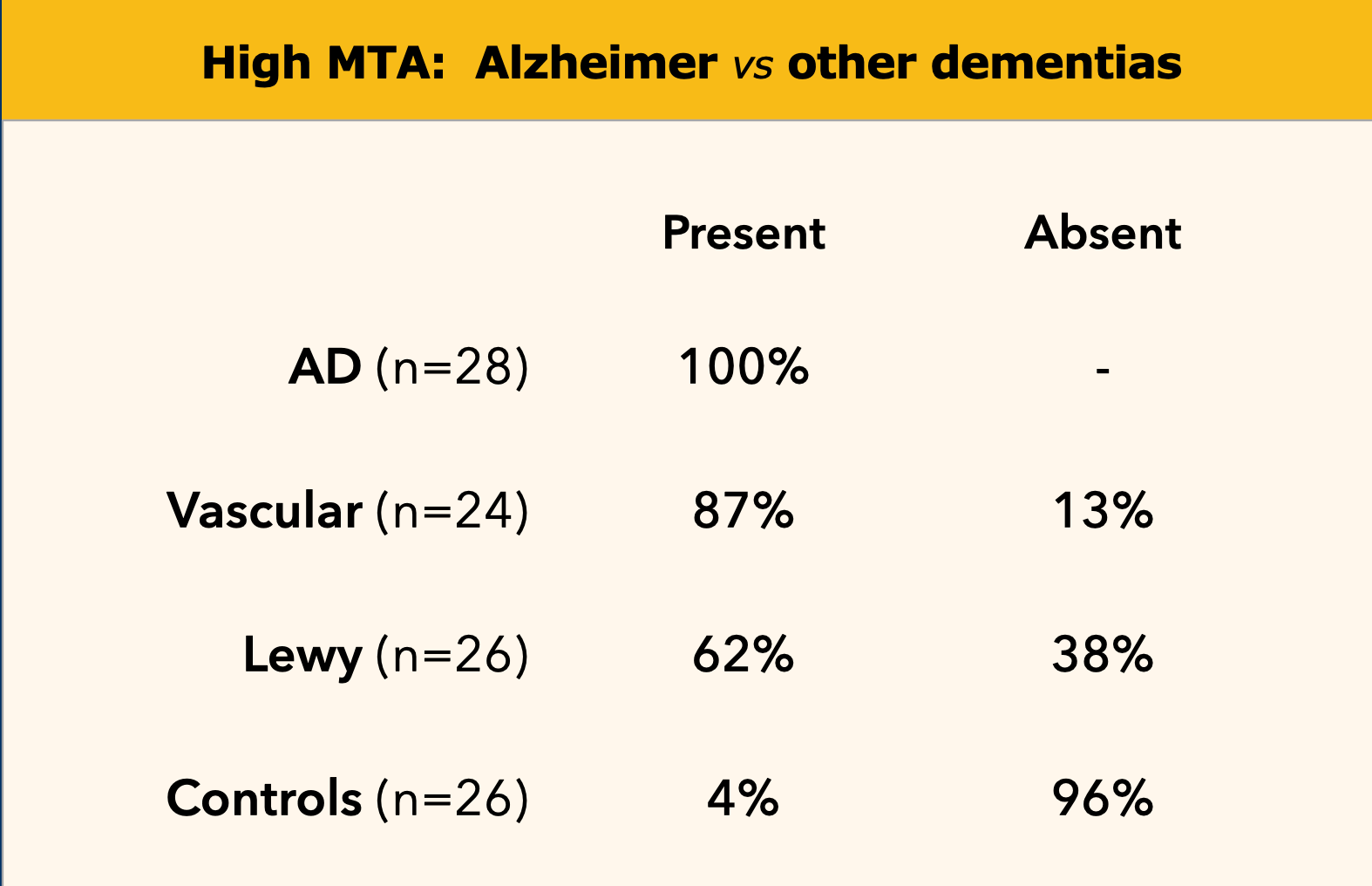

Medial temporal lobe atrophy in Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and in controls.

Medial temporal lobe atrophy in Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and in controls.

A high MTA-score is very sensitive for the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and is present in the vast majority of patients with AD, while in controls a positive score is almost always absent (table on the left).

Therefore it is a good test to discern controls from patients with AD.

This test is not completely specific for AD however, as MTA can also be found in other forms of dementias (7).

On the other hand if a patient with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) a possible 'prodromal state of AD' has a negative MTA-score, it is very unlikely that this patient will develop AD (high sensitivity yields high negative predictive value), except in very young subjects, in whom a more posterior pattern of atrophy can be observed in AD.

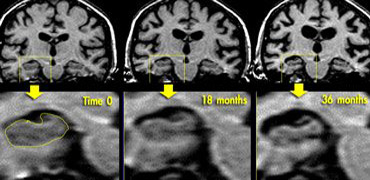

Coronal T1WI of the hippocampus demonstrating progressive atrophy in familial AD (images kindly provided by Nick Fox).

Coronal T1WI of the hippocampus demonstrating progressive atrophy in familial AD (images kindly provided by Nick Fox).

If there is a strong suspicion of Alzheimer's disease, it can be useful to repeat the examination to see if there is any progress of the (medial temporal lobe) atrophy.

The images show a follow-up examination at 18 and 36 months in a patient who was at risk for familial AD, demonstrating progression of the disease.

An alternative approach would be to perform a SPECT- or PET-scan to look for changes in perfusion/metabolism of the temporo-parietal cortex, as these changes precede the development of atrophy.

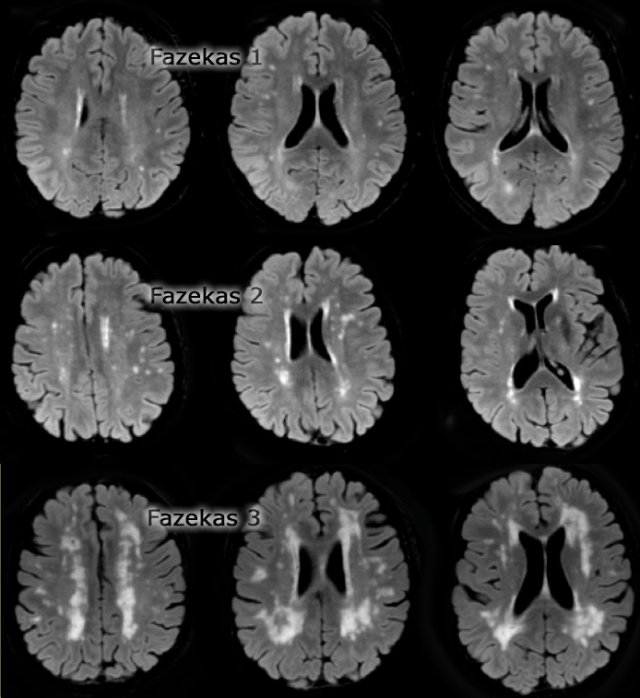

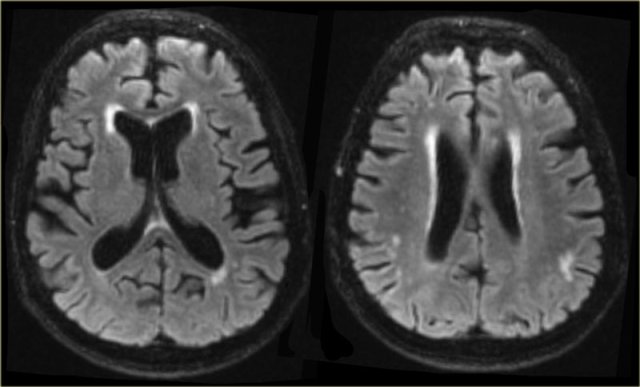

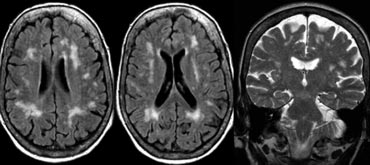

Fazekas scale for WM lesions

On MR, white matter hyperintensities (WMH) and lacunes - both of which are frequently observed in the elderly - are generally viewed as evidence of small vessel disease.

The Fazekas-scale provides an overall impression of the presence of WMH in the entire brain.

It is best scored on transverse FLAIR or T2-weighted images.

Score:

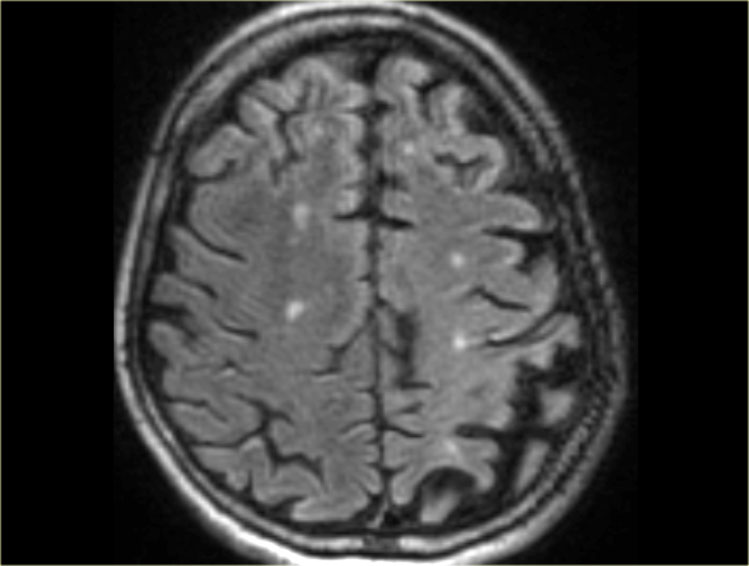

- Fazekas 0: None or a single punctate WMH lesion

- Fazekas 1: Multiple punctate lesions

- Fazekas 2: Beginning confluency of lesions (bridging)

- Fazekas 3: Large confluent lesions

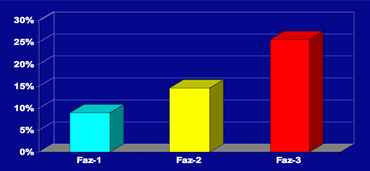

Fazekas 1 is considered normal in the elderly.

Fazekas 2 and 3 are pathologic, but may be seen in normally functioning individuals.

They are however, at high risk for disability.

In 600 normally functioning elderly people the Fazekas score predicted disability within one year (table).

In the Fazekas 3 group 25% was disabled within one year (10).

Three year follow-up shows that severe white matter changes independently and strongly predict rapid global functional decline (17).

Normal ageing

The findings in a normally aging brain can overlap with findings in dementia.

As implicated earlier, there may be some degree of atrophy, though mainly of the white matter with increasing prominence of the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) spaces and non-specific fronto-parietal sulcal widening.

There may also be some degree of medial temporal lobe atrophy.

A MTA-score of 2 for individuals older than 75 years of age may be normal.

As the brain ages, there is an increasing deposition of iron in specific areas of the brain: mainly the basal ganglia, nucleus ruber and pars reticluaris of the substantia nigra.

There also may develop a rim of high signal intensity on T2W and FLAIR images around the ventricles, known as caps and bands (figure).

A limited amount of white matter hyperintensities may also occur in the normally ageing brain (Fazekas grade 1).

Lacunes are always pathological.

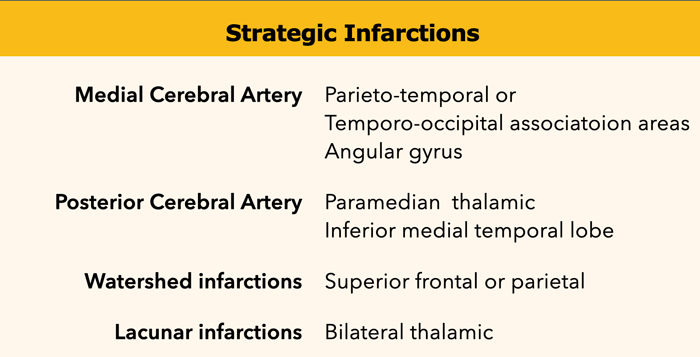

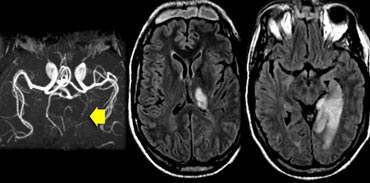

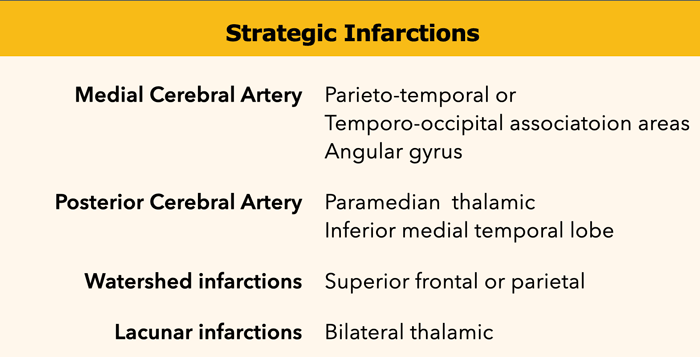

Strategic infarctions

Strategic infarctions are infarctions in areas that are crucial for normal cognitive functioning of the brain.

These areas are summarized in the table.

Strategic infarctions are best seen on transverse FAIR and T2W sequences.

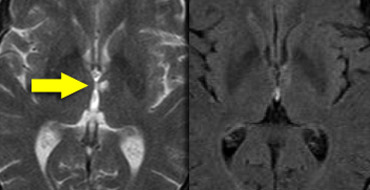

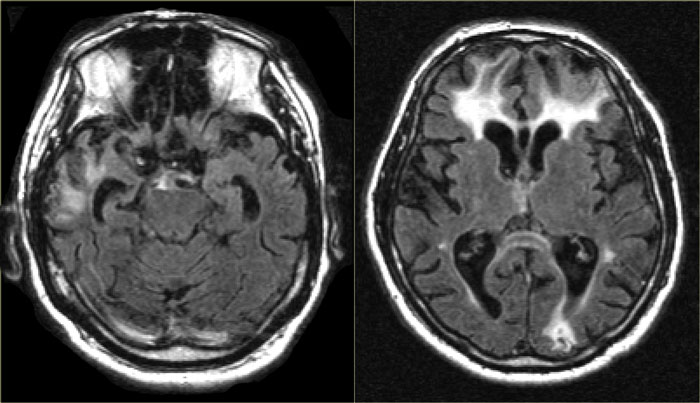

The images show bilateral thalamic infarctions - lesions often associated with cognitive dysfunction.

Study the images of two different patients.

Then continue reading.

The image on the far left shows an infarct in the vascular territory of the Posterior Cerebral Artery (PCA), with involvement of the inferior medial temporal lobe which includes the hippocampus.

This is a strategic infarction, since it is in the dominant hemisphere, it will result in cognitive dysfunction.

The image next to it is a transverse FLAIR image showing another infarct in the PCA-territory, with involvement of the temporo-occipital association area.

This is another example of a strategic infarction that can result in cognitive dysfunction.

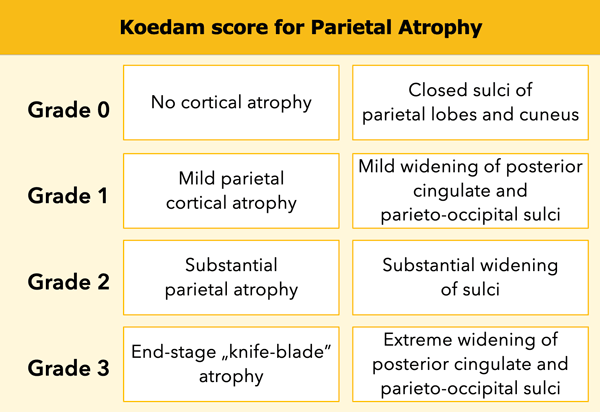

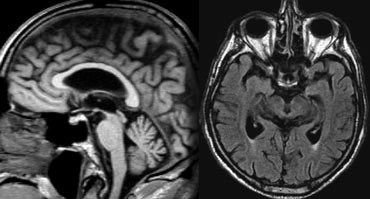

Koedam score for Parietal Atrophy

In addition to medial temporal lobe atrophy, parietal atrophy also has a positive predictive value in the diagnosis of AD.

Atrophy of the precuneus is particularly characteristic of AD (15).

This is particularly the case in young patients with AD (presenile AD), who may have normal MTA-scores.

The Koedam scale rates parietal atrophy - assessed in sagittal, coronal and axial planes.

In these planes, widening of the posterior cingulate and parieto-occipital sulci as well as parietal atrophy (including the precuneus) is rated (Table).

Koedam scale grade 0-1

Sagittal T1-, axial FLAIR- and coronal T1-weighted images illustrating the Koedam scale of posterior atrophy.

When different scores are obtained in different orientations, the highest score must be considered (16).

Koedam scale grade 2-3

Sagittal T1-, axial FLAIR- and coronal T1-weighted images illustrating the Koedam scale of posterior atrophy.

The yellow arrows point to extreme widening of the posterior cingulate en parieto-occipital sulci in a patient with grade 3 posterior atrophy.

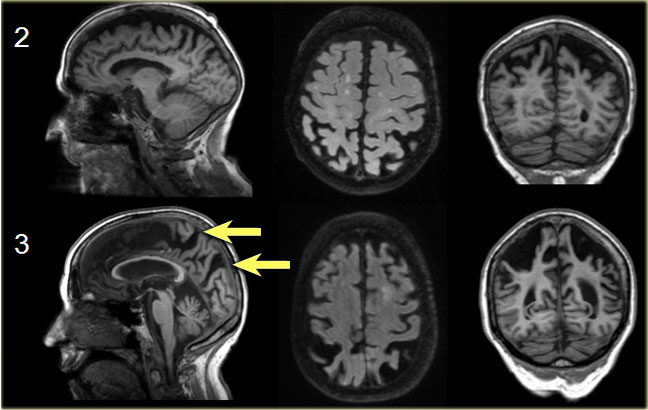

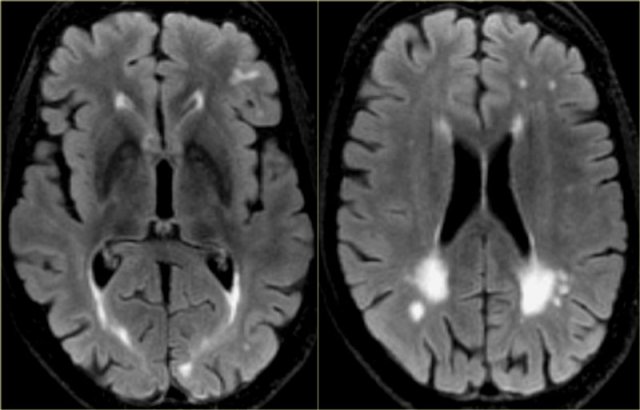

FDG-PET

In addition to clinical findings, CSF and MRI, PET-imaging is useful in diagnosing AD.

In AD FDG-PET can show hypometabolism in the temporoparietal regions and/or the posterior cingulum.

This may help differentiate AD from FTD, which shows frontal hypometabolism on FDG-PET.

The images show FDG-PET and axial FLAIR images of a normal subject and of patients with AD and FTD.

FDG-PET (top row) and axial FLAIR images of a normal subject and of AD and FTD patients.

In AD there is a decreased metabolism of the parietal lobes (yellow arrows), whereas in FTD, there is frontal hypometablism (red arrows).

Specific Diseases

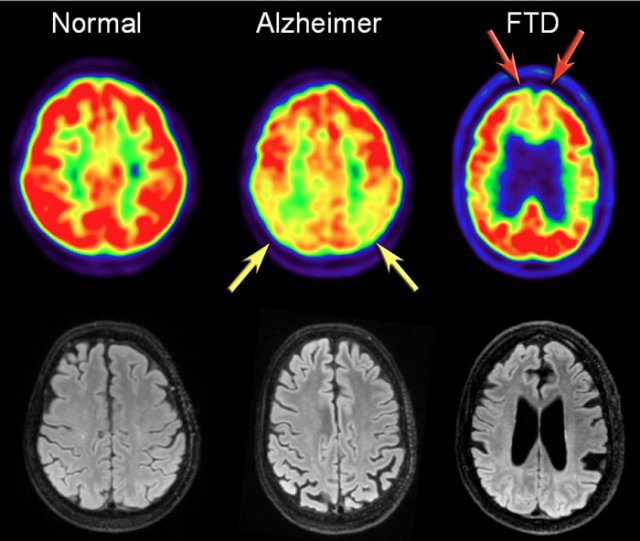

The prevalence of specific forms of dementia is age-dependent.

In patients

In patients > 65 years there are more cases of senile AD and vascular dementia.

In many older patients with manifest AD there is co-existing vascular disease, which contributes to the demented state.

Alzheimers Disease

AD accounts for 50%-70% of all cases of dementia in the elderly population.

Age is a strong risk factor, with the disease affecting approximately 8% of individuals over the age of 65 and 30% over the age of 85 years.

The progression of AD is gradual and the average patient lives 10 years after the onset of symptoms.

With the increasing percentage of elderly in the population, the prevalence of AD is expected to triple over the next 50 years.

In end-stage AD there is widespread atrophy, which is no different from other end-stage dementias.

In imaging we therefore have to try to identify AD in an earlier stage and we have to concentrate on the hippocampus and the medial temporal lobe, because that is where AD starts.

The role of MRI in the diagnostic process of AD is twofold:

- Rule out other causes of cognitive impairment.

- Identify early onset AD for possible innovative therapy and counseling

Study the image, then continue reading.

The findings are consistent with the diagnosis of end stage AD, because there is:

- Extreme hippocampal and medial temporal lobe atrophy (MTA score: 4)

- Severe global atrophy (GCA scale: 3)

It is not specific for AD however, since severe GCA occurs in other end-stage disorders as well

Presenile AD

Presenile AD ( Although there usually is some mild hippocampal atrophy, the most striking finding is parietal atrophy with atrophy of the posterior cingulum and the precuneus; the hippocampus can be normal.

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

Mild cognitive impairment is a relatively recent term used to describe people who have some problems with their memory, but do not actually have dementia, since dementia is defined as having problems in two or more cognitive domains.

Some of these patients will be in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease or another dementia, so it is important to identify them.

Finding MTA is a strong risk-factor for progression to dementia.

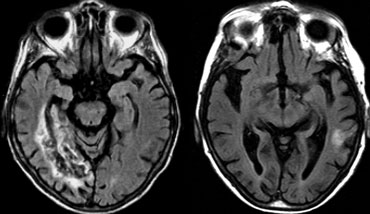

Vascular Dementia (VaD)

Vascular dementia (VaD) is thought to be the second most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer's disease.

It can sometimes be distinguished from AD by a more sudden onset and association with vascular risk factors.

VaD can be characterized by its stepwise deterioration with periods of stability followed by sudden decline in cognitive function.

Most patients, however, have small vessel disease, which is typified by a more gradual and subtle pattern of deterioration.

Control of vascular risk factors is the treatment of choice, but cholinesterase inhibitors (drugs that are being used in AD) are also increasingly being used to treat vascular dementia.

The images show a patient with a strategic PCA infarction involving the hippocampus.

This type of infarct can result in sudden dementia if located in the dominant hemisphere.

It will usually not result in dementia if it occurs in the non-dominant hemisphere.

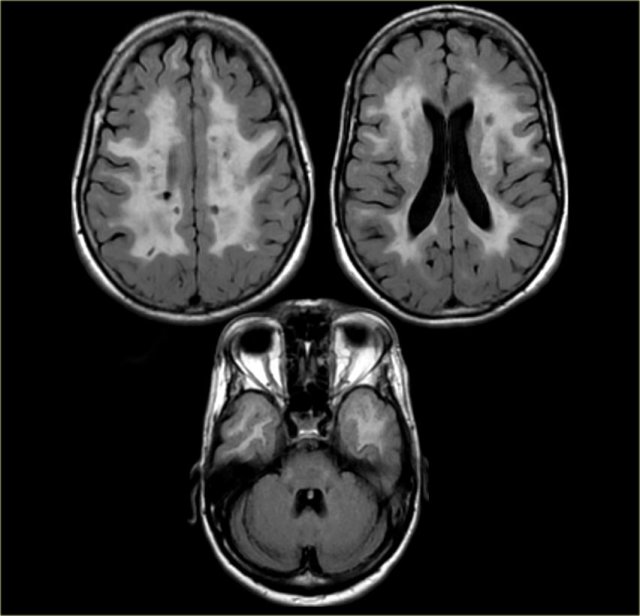

In most patients with VaD there is diffuse white matter disease with large confluent lesions (Fazekas 3).

In some of these patients the ventricles may be dilated due to global atrophy and some will also have medial temporal lobe atrophy.

The images are of a patient who had VaD, but the medial temporal lobe was normal.

Strategic infarcts and small vessel disease

Cognitive dysfunction in VaD can be the result of (2):

- Large vessel infarctions:

- Bilateral in the anterior cerebral artery territory.

- Parietotemporal- and temporo-occipital association areas of the dominant hemisphere (angular gyrus included)

- Posterior cerebral artery territory infarction of the paramedian thalamic region and inferior medial temporal lobe of the dominant hemisphere

- Watershed infarctions in the dominant hemisphere (superior frontal and parietal)

- Small vessel disease:

- Multiple lacunar infactions in frontal white matter (>2) and basal ganglia (>2)

- WMLs (at least more than 25% of WM)

- Bilateral thalamic lesions

There is an increasing awareness for the importance of small vessel disease as a predictor of cognitive decline and dementia.

Moreover, it seems to amplify the effects of pathologic changes of Alzheimer's disease.

On the left we see a patient who was diagnosed as having VaD.

White matter disease is seen as severe WMH (hypointense on T1) in the periventricular regions.

In addition to these vascular changes, there is also MTA.

Presumably this patient has both VaD and AD, a finding seen in many elderly patients.

These findings should be described separately as it may have therapeutic consequences.

The problem however is, that white matter hyperintensities and lacunes are also frequently observed in non-demented elderly and at some level can be regarded as normal findings in aging.

To overcome this problem the NINDS-AIREN International Work Group has formulated criteria for the history and physical, radiological, (see above) and pathological examination to classify patients as having possible, probable and definite VaD.

However considerable interobserver variability exists for the assessment of the radiological part of these NINDS-AIREN criteria and some level of training is mandatory (2).

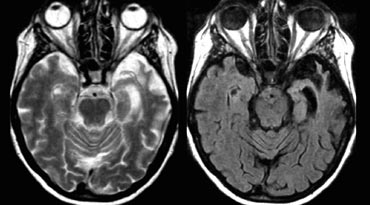

The medial nuclei of the thalamus play an important role in memory and learning.

A large unilateral infarction or bilateral infarctions in this region can cause dementia.

You have to pay special attention to these areas to find these small infarctions.

On FLAIR images you will easily miss these infarctions, because they can be isointense to the surrounding structures (8).

A high resolution T2WI is needed to detect these thalamic infarcts.

FLAIR in the infratentorial region and in the spinal cord is of limited value as it suppresses not only the signal of water, but also pathology with a long T1-relaxation time.

This phenomenon can also be seen in the detection of Multiple Sclerosis, where FLAIR is of limited value in the infratentorial region and of no use in the spinal cord.

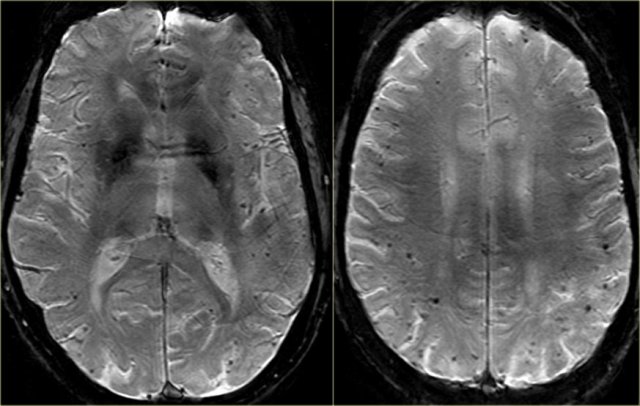

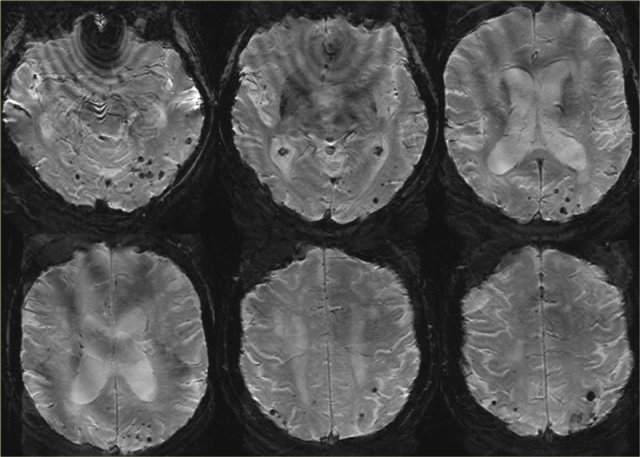

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA)

Dementia may be the clinical presentation in CAA, a condition in which ?-amyloid is deposited in the vessel walls of the brain.

The result is hemorrhage, usually microhemorrhages, but also subarachnoid hemorrhage or lobar hematomas may occur.

On MR, the T2* sequence will show multiple microhemorrhages, typically in a peripheral location (as opposed to hypertensive microhemorrhages, which are usually more centrally located, e.g. in the basal ganglia and thalami).

In addition, FLAIR will reveal moderate to sever white matter hyperintensities (Fazekas grade 2 or 3)

T2* images in a patient with CAA show multiple peripherally located microbleeds.

FLAIR images of the same patient show Fazekas 2 white matter hyprintensities.

T2* images in a patient with CAA microbleeds.

T2* images demonstrate multiple lobar microbleeds in a patient with CAA.

End stage FTLD with striking atrophy of frontal and temporal lobes. No artophy of parietal and occipital lobes. Courtesy Webpath (11).

End stage FTLD with striking atrophy of frontal and temporal lobes. No artophy of parietal and occipital lobes. Courtesy Webpath (11).

Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (FTLD )

FTLD, formerly called Pick's disease, is a progressive dementia, that accounts for 5-10% of cases of dementia., and occurs relatively more frequently in presenile subjects

FTLD is clinically characterized by behavioral and language disturbances that may precede or overshadow memory deficits.

There is currently no treatment for this condition.

Imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis as the findings are easy to recognize.

Radiological findings are pronounced atrophy of frontal and / or temporal lobes.

In some forms of FTLD the atrophy might be strikingly asymmetric, e.g. in Semantic Dementia, a disease subtype with progressive aphasia and left-sided temporal lobe degeneration.

FTLD: T2WI and FLAIR with 'knife blade' atrophy of left temporal lobe with normal right temporal lobe

FTLD: T2WI and FLAIR with 'knife blade' atrophy of left temporal lobe with normal right temporal lobe

The images are of a patient with progressive aphasia.

The most prominent finding is the striking asymmetric atrophy of the temporal lobe on the left side with not only atrophy of the hippocampus, but also the temporal poles.

The atrophy has resulted in gyri that appear as sharp as knives ('knife blade atrophy').

There is also some increased signal intensity seen on the FLAIR image, probably due to gliosis.

These findings are pathognomonic for the diagnosis of FTLD.

Patients with left-sided temporal atrophy are usually clinically obvious.

Right-sided atrophy is usually not as easily recognized as these patients only present with subtle disturbances in recognizing faces.

Dementia with Lewy bodies

Dementia with Lewy bodies is responsible for approximately 25% of dementias and belongs to the atypical Parkinson syndromes together with progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and multi-system atrophy (MSA).

The clinical manifestations can be similar to that of AD or dementia associated with Parkinson's disease.

Patients typically present with one of three symptom complexes: detailed visual hallucinations, Parkinson-like symptoms and fluctuations in alertness and attention.

Pathologically, the disease is characterized by the presence of Lewy bodies in various regions of the hippocampal complex, subcortical nuclei and neocortex with a variable number of diffuse amyloid plaques.

Cholinesterase inhibitors are currently the treatment of choice for this condition.

The role of imaging is limited in Lewy body dementia.

Usually the MR of the brain is normal, including the hippocampus.

This finding is important as it enables us to differentiate this disease from Alzheimer';s disease, the main differential diagnosis.

Nuclear imaging can be used to demonstrate an abnormal dopaminergic system (so-called DaTscan)

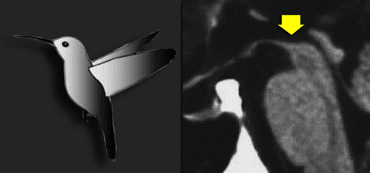

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)

PSP is also one of the atypical parkinsonian syndromes.

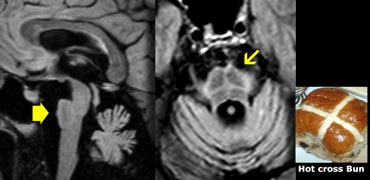

In PSP there is pronounced atrophy of the midbrain (mesencephalon), which accounts for the typical upward gaze paralysis.

Normally the upper border of the midbrain is convex.

The atrophy of the midbrain in PSP results in a concave upper border of the midbrain with the typical 'humming bird sign' (figure).

Multi System Atrophy (MSA)

MSA is also one of the atypical parkinsonian syndromes.

MSA is a rare neurological disorder characterized by a combination of parkinsonism, cerebellar and pyramidal signs, and autonomic dysfunction.

MSA can be classified as MSA-C, MSA-P or MSA-A.

In MSA-C (formerly known as sporadic olivopontocerebellar atrophy or sOPCA) the cerebellar symptoms predominate, whereas in MSA-P the parkinsonian symptoms dominate (MSA-P was formerly known as striatonigral degeneration).

MSA-A is the form in which autonomic dysfunction predominates and is the new term for what was formerly known as Shy-Drager syndrome.

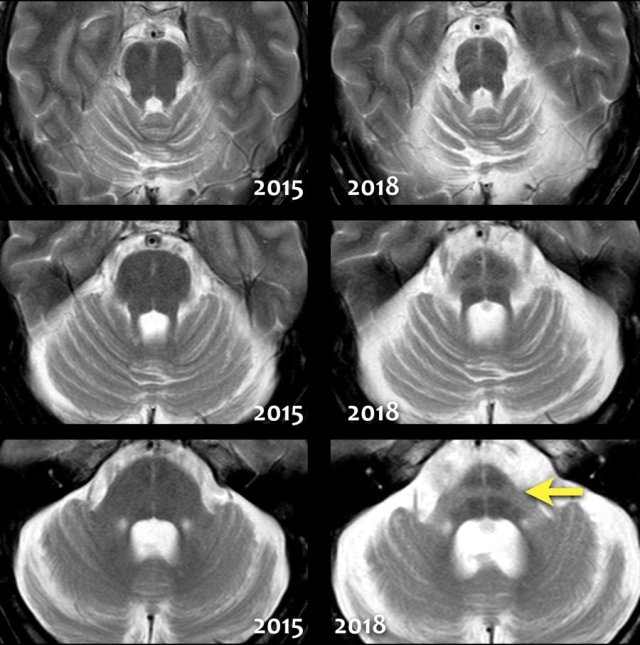

In MSA there is pronounced cerebellar atrophy and severe atrophy of the pons.

In MSA-P: low T2 SI dorsolateral putamen and slit-like increased SI lateral to putamen on T2.

In contrast to PSP, we don't see the humming bird sign, because the midbrain has a normal convex upper border.

The so-called 'hot cross bun sign', which is a result of pontine hyperintensity, is typical for MSA-C.

Notice the extreme atrophy of the pons and the cerebellum in this patient when we compare images of 2015 with images of 2018.

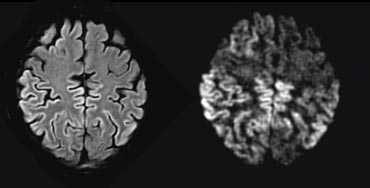

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD)

CJD is a very rare and incurable neurodegenerative disease, caused by a unique type of infectious agent called a prion.

The first symptom of CJD is rapidly progressive dementia, leading to memory loss, personality changes and hallucinations.

The disease is characterized by spongiform changes in the cortical and subcortical gray matter, with loss of neurons and replacement by gliosis.

The abnormalities can sometimes be detected on FLAIR, but are most conspicuous on DWI sequences, affecting either the striatum, the neo-cortex, or a combination of both.

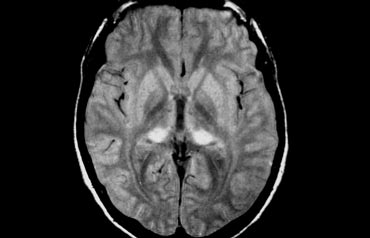

New variant CJD

New variant of CJD is also known as the 'mad cow disease' (12).

It is a disease fortunately hardly encountered anymore.

In this variant the changes are seen in the posterior part of the thalamus, called the pulvinar.

Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD)

CBD is a rare entity which may present with cognitive dysfunction, usually in combination with Parkinson-like symptoms.

The so-called 'Alien-hand' syndrome is a typical manifestation.

MRI shows asymmetric parietal cortical atrophy, sometimes with associated hyperintensity of the white matter on T2W images.

Axial FLAIR image shows striking asymmetric cortical parietal atrophy in a patient with CBD.

Huntington Disease

Huntington disease is a hereditary neurodegenerative disease (autosomal dominant trait, but often de novo mutations), and can present with early onset dementia as well as choreoathetosis and psychosis.

Imaging shows characteristic atrophy of the caudate nucleus and subsequent enlargement of the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles.

Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencehalopathy (CADASIL)

CADASIL is another hereditary disease which may present with a progressive cognitive dysfunction.

Other presenting symptoms include migraines, stroke-like episodes and behavioral disturbances. It affects the small vessels of the brain.

Confluent white matter hyperintesities in the frontal and especially anterior temporal lobes in combination with (lacunar) infarcts and microbleeds are seen on imaging.

The FLAIR images show classic findings in CADASIL - confluent white matter hyperintensities with lacunar infarcts and involvement of the anterior temporal lobes.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Long term sequelae of traumatic brain injury such as cerebral contusions and diffuse axonal injury (DAI) may include cognitive impairment.

Frontobasal/temporal parenchymal loss or T2* black dots typical for DAI in a patient with a history of trauma must therefore be taken into consideration when assessing MR images for dementia.

The FLAIR images show classic post-traumatic tissue loss with gliosis in both frontal lobes, the left occipital lobe and right temporal lobe.

In the book on the left you can find more information about the role of MR in dementia (9).

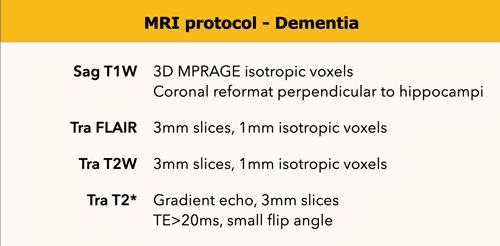

MR protocol

Coronal-oblique T1-weighted images are used for the assessment of medial temporal lobe and hippocampal atrophy.

They are obtained in a plane orthogonal to the long axis of the hippocampus; this plane is orientated parallel to the brainstem.

These should be thin-section images and are ideally obtained by reformatting a sagittal 3D T1 sequence through the entire brain.

Additional sagittal reconstructions will enable the assessment of midline structures as well as parietal atrophy, which may be involved in certain neurodegenerative disorders.

FLAIR images are used to assess global cortical atrophy (GCA), vascular white matter hyperintensities and infarctions.

T2-weighted images are used to assess infarctions, in particular lacunar infarctions in the thalamus and basal ganglia, which can be missed on FLAIR images.

T2*-weighted images are necessary to detect microbleeds in amyloid angiopathy. These images can also depict calcifications and iron deposition.

DWI should be considered as a supplemental sequence in young patients or in rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disorders (DD - vasculitis, CJD).

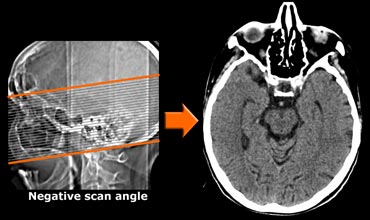

CT protocol

CT can be useful when contraindications prevent MRI or when the only reason for imaging is to rule out surgically treatable causes of cognitive decline.

In the transverse plane the scan angle should be parallel to the long axis of the temporal lobe.

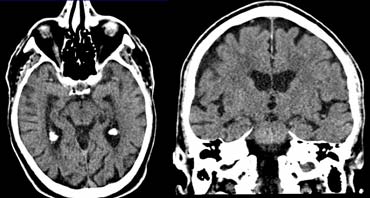

Use of multi-detector CT will enable coronally reformatted images to be reconstructed perpendicular to the long axis of the temporal lobe for optimal vizualisation of the hippocampus.

Use of multi-detector CT will enable coronally reformatted images to be reconstructed perpendicular to the long axis of the temporal lobe for optimal vizualisation of the hippocampus.