Crohn's disease - role of Ultrasound

Frank Zijta, Inge Vanhooymissen and Julien Puylaert

Haagland Medical Center in the Hague and the Academical University Medical Center in Amsterdam

In this section we will discuss the sonographic features used to evaluate Crohn’s disease.

After reading this section, you will be able to:

- Recognize normal bowel wall appearance and morphological changes of the bowel wall in Crohn’s disease, using ultrasound.

- Identify the classic US features of Crohn’s disease.

- Sonographically discriminate Crohn’s disease from other bowel conditions as infection, neoplasia and ischemia mimicking Crohn’s disease.

Press ctrl+ for larger images and text on a PC or ⌘+ on a Mac. Most images can be enlarged by clicking on them.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, recurrent inflammation of the bowel wall of unknown origin.

The disease has a tendency for transmural progression with ulceration, abscesses, fistula formation, fibrosis and (intermittent) luminal obstruction. Although Crohn’s disease can involve the entire gastrointestinal tract, colon and ileocecal region are the most frequently involved areas.

Patients with Crohn's disease often have longstanding, insidious and atypical symptoms leading to serious diagnostic delay of months to even years.

On the other hand, ileocecal Crohn disease may also present acutely with appendicitis-like symptoms or small bowel obstruction.

In both scenarios US can play an important role in making the correct diagnosis.

Apart from primary detection, US is also useful in:

- Monitoring disease activity during medical treatment (1,2,3)

- Guiding percutaneous abscess drainage

- Differentiating Crohn’s colitis from ulcerative colitis

- Demonstrating acute prestenotic dilatation in patients with intermittent obstruction.

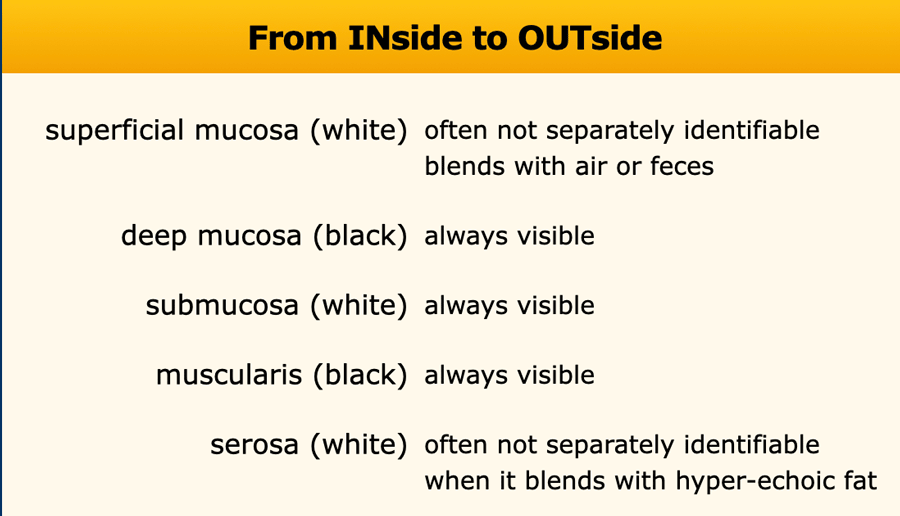

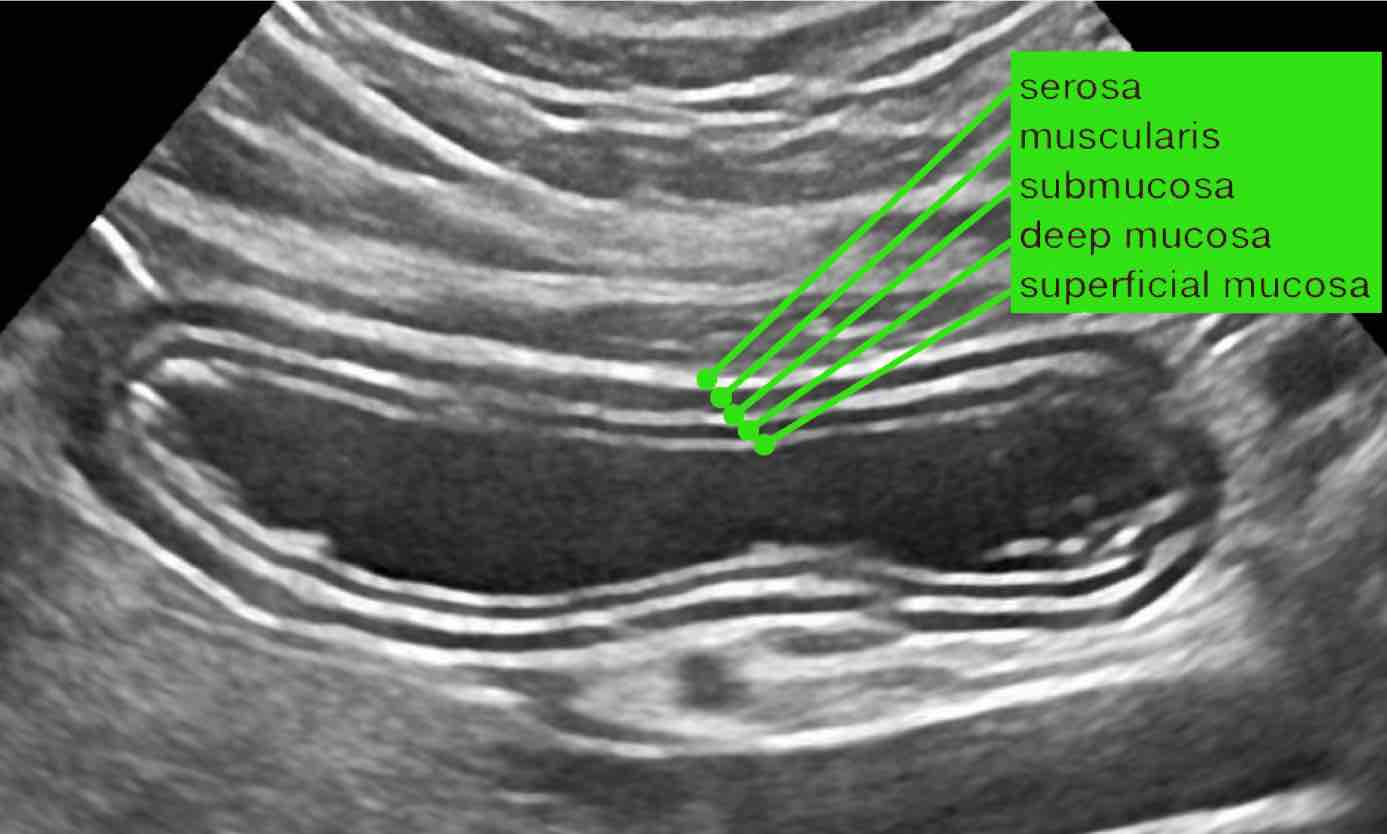

Normal US anatomy

The US architecture of the normal bowel wall has a typical five-layered morphology of alternating echogenicity, closely corresponding to the histological layers of the bowel wall.

This US architecture is essentially identical from the stomach to the rectum.

The normal US anatomy is outlined in the section Ultrasound of the GI tract - Normal Anatomy

US signs of ileocecal Crohn’s disease

Bowel wall thickening

In ileocecal Crohn’s disease, typically all bowel wall layers are involved, and the normal stratification is often locally disturbed. US shows marked mural thickening, predominantly in the terminal ileum, but cecum and appendix can also be involved.

Bowel wall thickening is most prominent in the hyperechoic submucosal layer, representing deposition of fat and fibrous tissue as a result of chronic bowel inflammation (4).

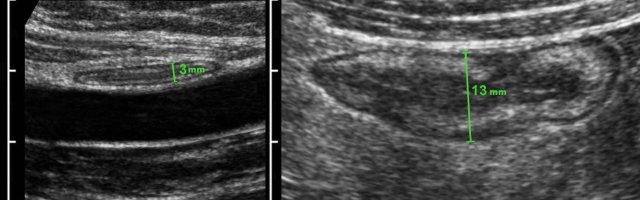

Difference between size and compressibility of normal ileum (left) and Crohn affected ileum during intermittent graded compression.

Using graded compression, two adjacent bowel segments are compressed against the iliopsoas muscle.

The ventral segment is normal and is easily compressed, while the Crohn’s loop can hardly be compressed.

Measuring bowel wall thickness is best and most reproducibly performed during compression, as here in a normal individual (left) and in a patient with Crohn’s disease (right).

Measurements are performed from outer contour of the muscular layer to the opposite side, and then divided by 2, resulting in a wall thickness of 1.5 mm and 6.5 mm for normal resp. Crohn ileum.

See also the section Ultrasound of the GI tract - Normal Anatomy.

Transmural signature

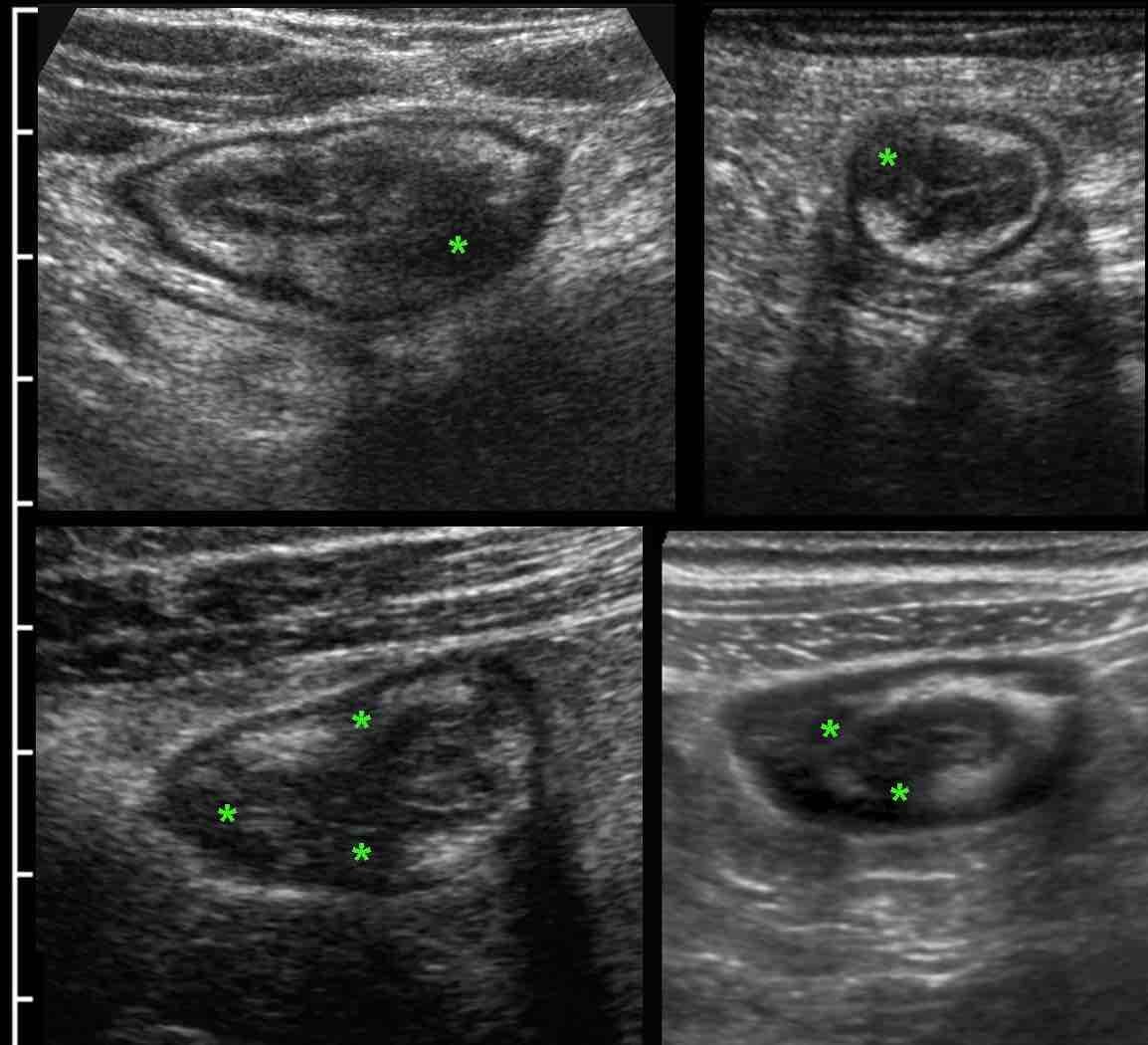

Commonly, at first presentation, US already reveals the characteristic transmural “signature” of Crohn’s disease.

This transmural progression is recognized as focal, hypoechoic changes (*) in the otherwise hyperechoic submucosa, closely correlating with endoscopic findings and active inflammatory histologic changes (4).

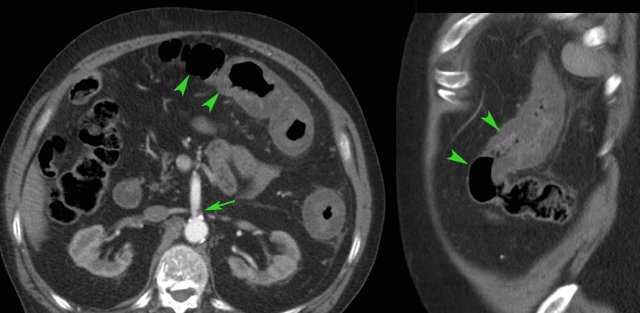

This 18-year old man was admitted with acute appendicitis-like symptoms and immediate CT was performed.

CT revealed evident ileal bowel wall thickening and a normal appendix (not shown here).

Subsequent US showed the typical characteristic transmural hypoechoic changes in the hyperechoic submucosa confirming Crohn’s ileitis.

Note the superior image resolution of US compared to CT.

In patients with manifest active Crohn’s disease, the normal US architecture of the bowel wall may be lost diffusely.

Note the hyperechoic fatty tissue (fat) around the ileum, representing the inflamed mesentery and omentum, trying to wall off the imminent perforation.

In cases like this, the altered morphology and luminal narrowing may mimic malignancy.

Skip lesions

One of the features of Crohn’s disease is the patchy way it affects bowel.

This results in skip lesions, where large parts of the bowel are left unharmed.

The affected parts show a relatively sharp demarcation, the transition from normal (small arrows) to abnormal bowel (large arrows) being rather abrupt.

Ulceration

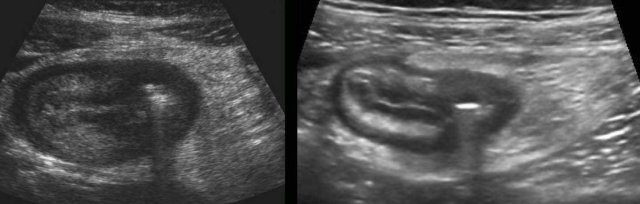

Bright eccentric foci within the hypoechoic areas are air-configurations representing deep ulceration, here depicted in two different patients.

These transmural ulcerations herald sinus tract formation, abscesses and fistula formation.

Note the partially surrounding inflamed fat, representing mesentery and omentum, at this point effectively walling off the imminent perforation.

Sinus tract formation

Air-configurations reaching beyond the peripheral borders of the bowel wall definitely indicate sinus tract formation.

Here an example in two different patients.

Abscess

Actively inflamed terminal ileum with a moderately demarcated hypoechoic area outside the bowel wall, surrounded by inflamed fat, indicates sinus tract and abscess formation.

Two patients with Crohn’s abscesses close to the ileum.

Note that abscesses in Crohn’s disease are often small and collapsed.

The explanation for this phenomenon is that these abscesses usually have an open connection to the ileal lumen, allowing pus to immediately evacuate to the bowel lumen when pressure goes up.

Fistulas

Ultimately sinus tract formation may proceed to fistula formation.

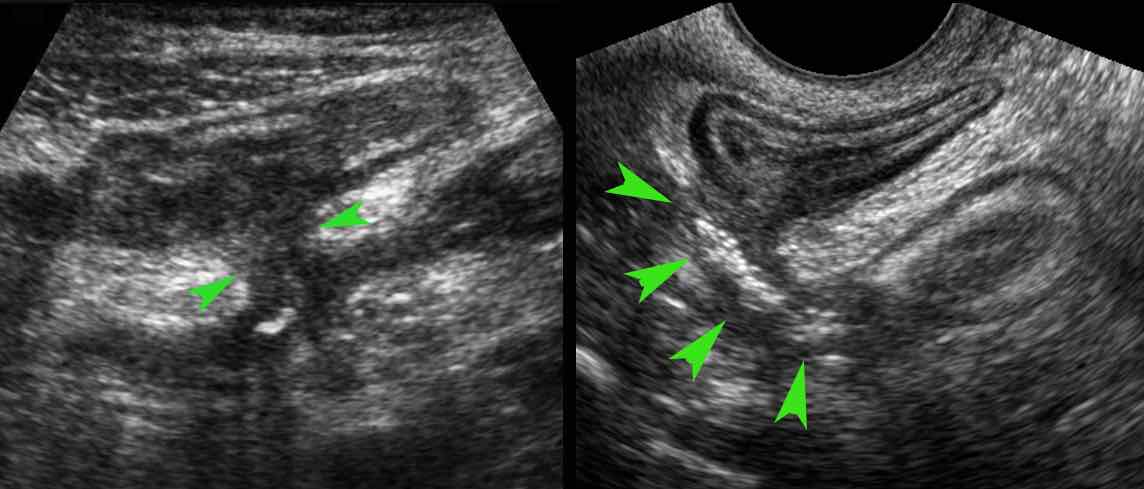

Here two examples of entero-enteric fistulization (arrowheads).

Fistula (arrowheads) from the terminal ileum to the appendix (arrows) in advanced ileocecal Crohn’s disease.

Note the hyperechoic fat, surrounding the fistula complex, representing omentum and mesentery effectively walling off a possible imminent perforation to the peritoneal cavity.

Due to its slow and insidious character, free perforation in Crohn’s disease is very rare.

Crohn abscess with bladder fistula

Two different patients with known Crohn’s disease who now both presented with micturition symptoms. In the left patient there is an abscess with secondary thickening of the bladder wall (arrowheads), in the right patient an enterovesical fistula is “in state of birth”, with massive thickening of the bladder wall (arrowheads).

Note that in 80 % of entero-vesical fistulae the cause is underlying diverticulitis while underlying cancer is the cause in 15 %.

Crohn’s disease is the third cause with about 5 %.

Ultimately sinus tract and abscess formation may result in a fistula.

The most frequent targets are small bowel, sigmoid and appendix.

Unusually, fistula to the bladder, the abdominal wall and iliopsoas muscle may occur.

In situations with complex enterocutaneous fistula involving multiple small bowel loops, CT or MRI enterography is the ideal modality (post-contrast T1 MRI), for pre-operative mapping and in follow-up, as in this patient.

In patients with such a complex anatomy, US plays a less important role than CT and MRI.

See also: Crohn's disease- Evaluation with MRI.

Stenosis and prestenotic dilatation

Inflammatory bowel wall thickening or the ensuing fibrotic strictures may finally result in luminal narrowing, stenosis and bowel obstruction.

The affected segment typically demonstrates dysfunctional motility.

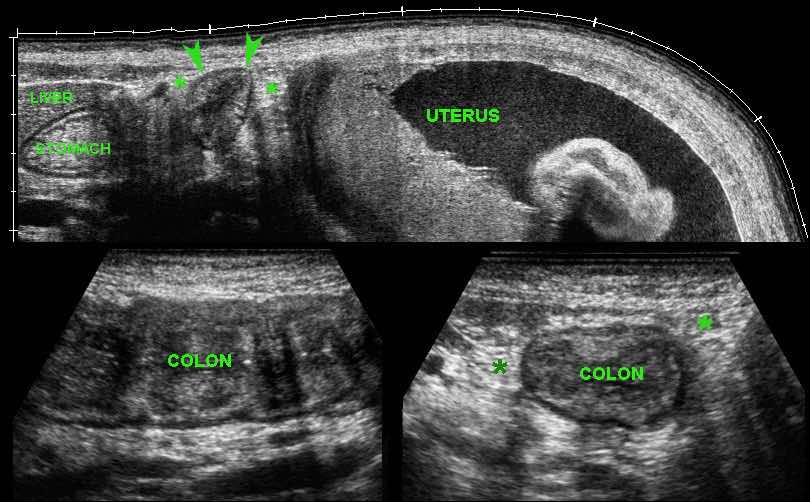

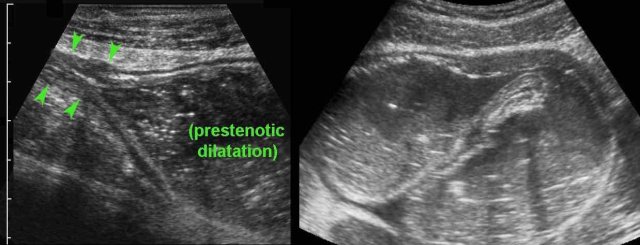

In case of acute abdominal symptoms, US can demonstrate the presence of prestenotic dilatation and therefore proves symptomatic stenosis.

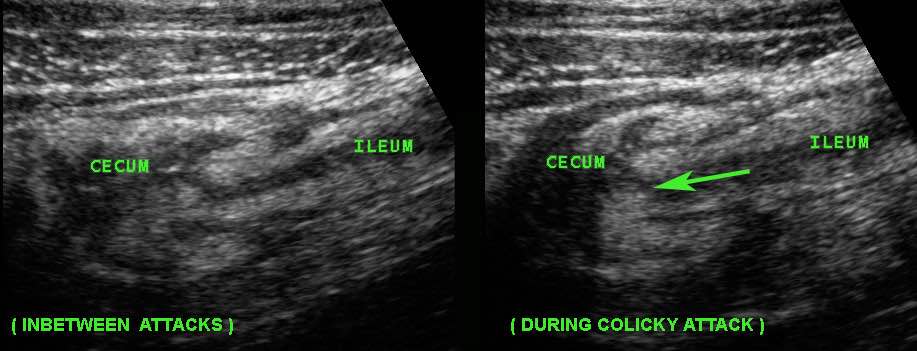

This young woman with known Crohn’s disease had intermittent colicky attacks that were never documented with imaging. She was asked to come back immediately during an attack to undergo US

Now US demonstrated marked prestenotic dilatation proximal to a short segment of abnormal ileum (arrowheads). Higher up there was another stenotic segment.

Since there was no reaction on medical therapy, this was considered a fibrotic stenosis and this patient underwent successful surgery.

Here a fibrotic stenosis in an ileal segment.

Note the prestenotic dilatation and absence of peristalsis at the level of the stricture (arrows).

In stenosing Crohn’s disease with long episodes of chronic recurrent small bowel obstruction, an interesting phenomenon in ileal loops may be observed, i.e. hypertrophy of the muscular layer.

This so-called “inflammation-smooth muscle hyperplasia axis” may be the most important factor in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s strictures.

Creeping Fat

In longstanding Crohn’s disease, “creeping fat” can be found, which is hypertrophied mesenteric fat “wrapped around” the affected bowel, most frequently in the ileocecal region.

It is recognized as a rather well-delineated, moderately compressible, fatty mass surrounding most of the circumference of the ileum, iso-echoic or slightly hyperechoic to normal fat.

During compression a “feather-like” pattern can be observed.

Old and inactive Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum in a now asymptomatic patient.

Note prominent thickening of the hyperechoic third layer, representing fatty deposition and loose connective tissue in the submucosa.

Here an example of appendiceal involvement in ileocecal Crohn’s disease.

Note prominent echolucent wall thickening of both terminal ileum and appendix (arrowheads).

This is not a true obstructive appendicitis and appendectomy should be avoided.

After medical therapy, there was normalization of both ileum, cecum and appendix on US.

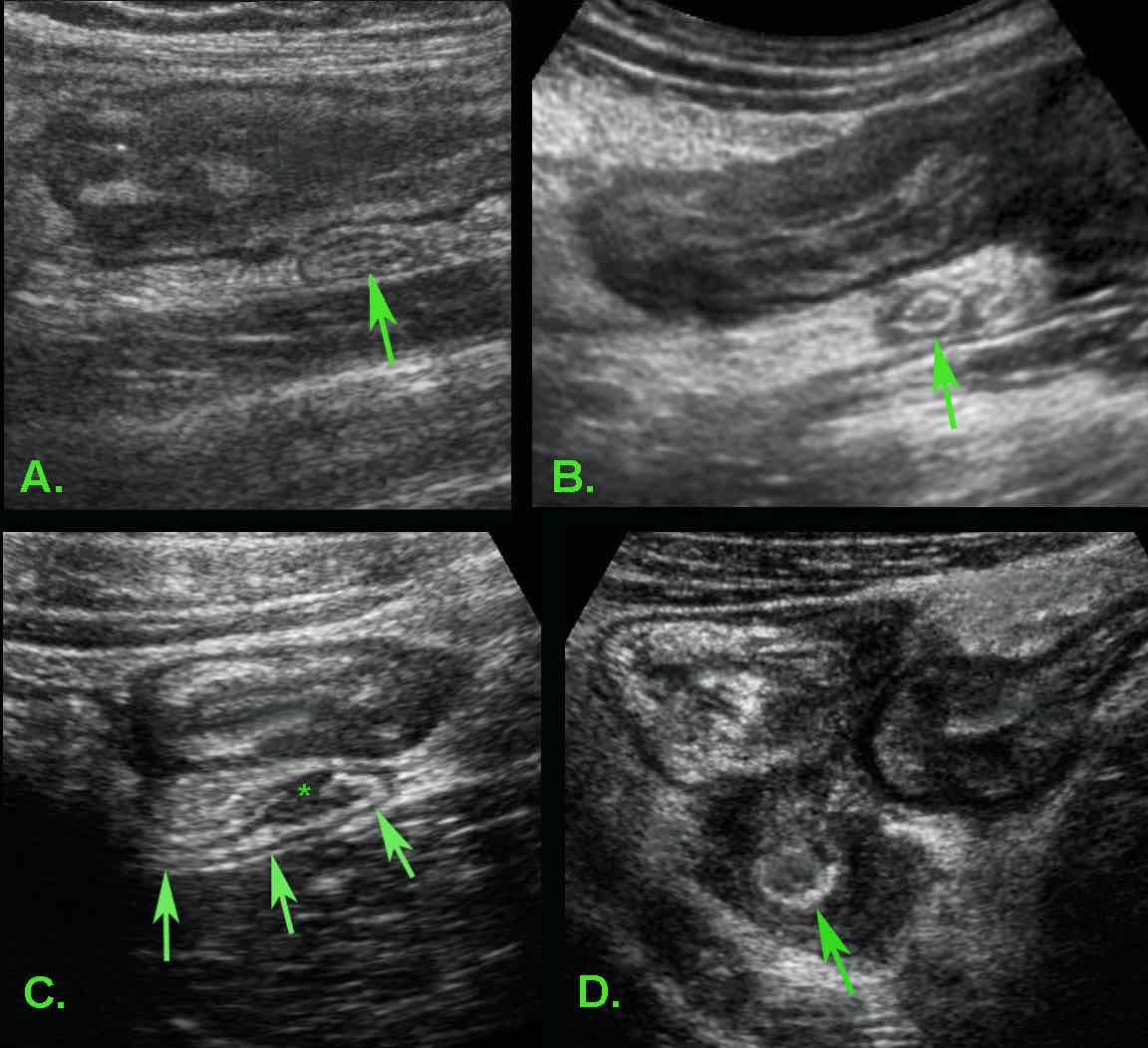

In most patients with ileocecal Crohn’s disease the appendix (arrow) is normal (A) or only minimally reactively thickened (B).

In some patients (C) with ileocecal Crohn’s disease, slight transmural changes in the appendix submucosa (*) indicate Crohn’s involvement of the appendix.

In D. there is severe involvement of ileum, cecum and appendix (arrow), with abundant surrounding inflamed fat.

Crohn’s involvement of the appendix in ileocecal Crohn’s disease is not an indication for appendectomy. It should not be confused with true, obstructive appendicitis.

If appendectomy is done in active ileocecal Crohn’s disease, the result may be a fistula.

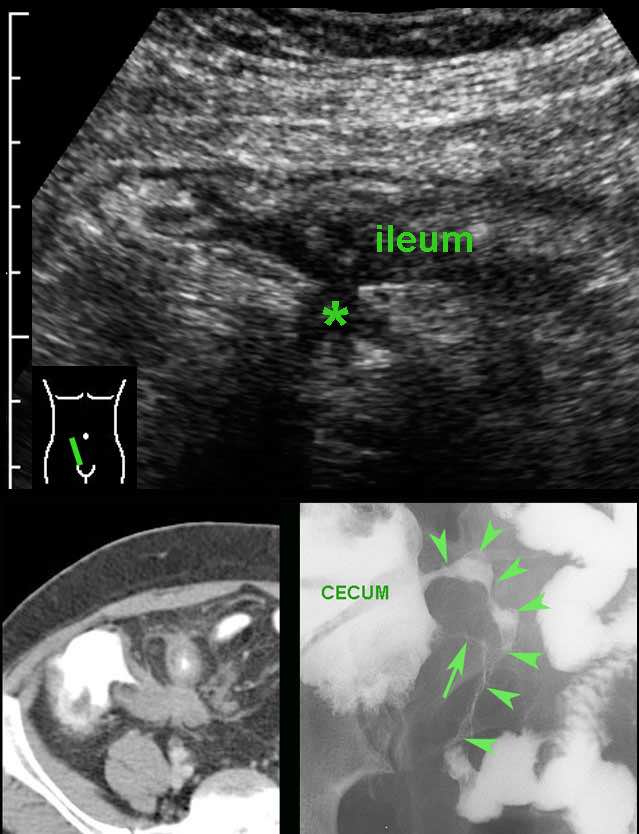

See * on US and ➛ on bariumstudy.

The fistula is located between the cecal pole and the terminal ileum (arrowheads).

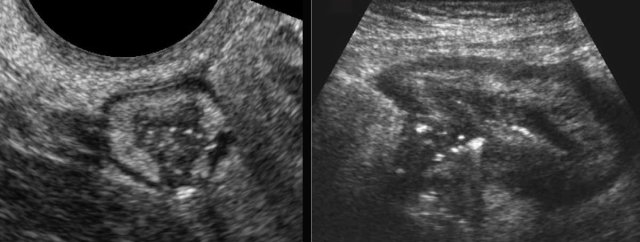

Isolated primary Crohn’s appendicitis is rare but it does exist.

In this patient there was transmural inflammation (*) and inflamed fat, indistinguishable from ordinary appendicitis.

Appendectomy is usually performed in such cases.

In truly isolated primary Crohn’s appendicitis there are seldom recurrences after appendectomy.

Differential Diagnosis

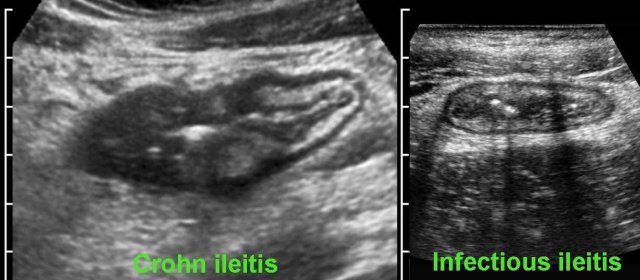

Infectious ileocolitis

One of the most important differential diagnosis is infectious colitis.

The main symptoms of infectious colitis are severe, often bloody diarrhoea, especially in Campylobacter and Salmonella colitis.

Other causative micro-organisms are E. coli, Shigella and several viruses.

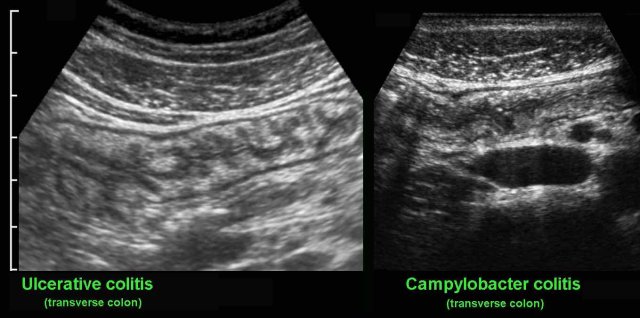

US reveals mucosal and submucosal thickening and hyperemia of the entire colon, which is impossible to differentiate from ulcerative colitis. Since in every patient with suspected IBD, repeated stool cultures are performed, the correct diagnosis is not a problem in most cases.

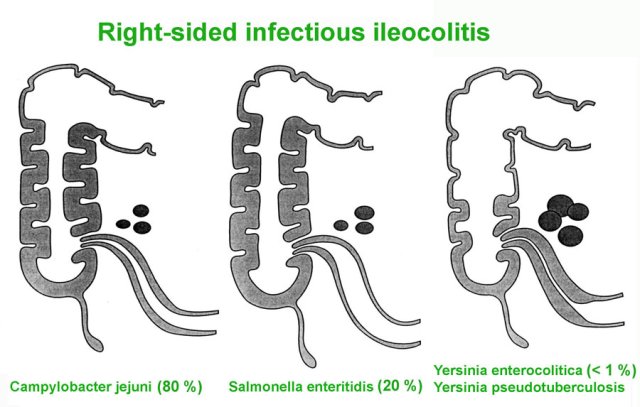

Right-sided infectious ileocolitis

In a small group of patients, especially young adults, the bacterial infection for unknown reasons may initially remain limited to ileum and right colon.

These patients present with prominent RLQ pain and have no or only mild diarrhoea.

This right-sided infectious ileocolitis may therefore present with symptoms mimicking appendicitis or ileocecal Crohn’s disease, and thus may lead to unnecessary surgery.

US plays an important role in the timely diagnosis.

The causative bacteria are Campylobacter (80%) and Salmonella (20%).

In the past, Yersinia was a frequent cause of infectious ileitis, closely mimicking Crohn’s disease both clinically and on US.

However, the incidence of Yersinia has strongly decreased over the last three decades and is seen only very rarely nowadays.

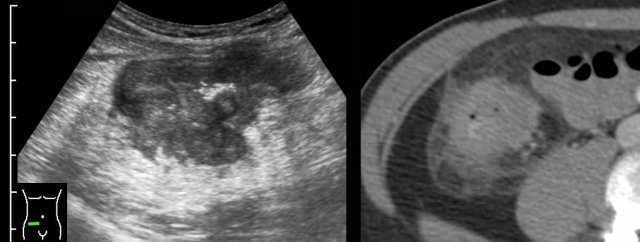

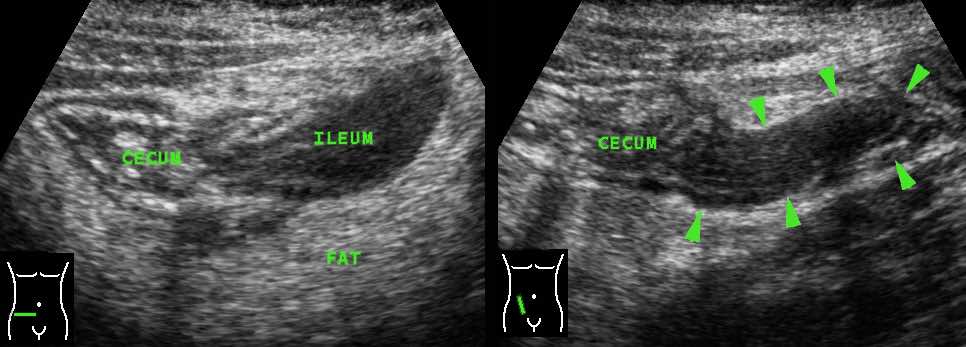

Classic US features of right-sided infectious ileocolitis in a young man.

Prominent mucosal and submucosal wall thickening of terminal ileum and right colon, enlarged inflamed mesenteric lymph nodes and a normal appendix.

Note the prominent ileocecal valve, due to both wall thickening of ileum and cecum in this patient with right-sided Campylobacter ileocolitis.

Right-sided infectious ileocolitis in a 33-year old man.

CT scan without contrast (history of severe allergy).

Prominent (sub)mucosal wall thickening of ileum and right colon.

Note also markedly enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes and normal appendix.

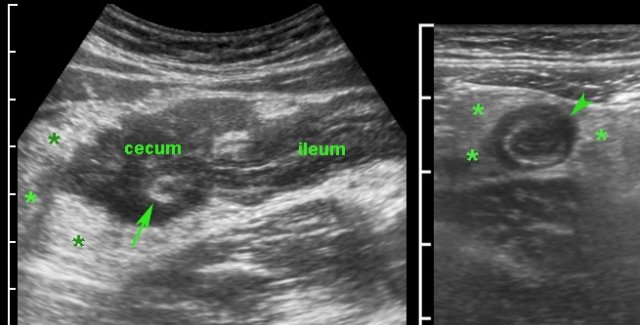

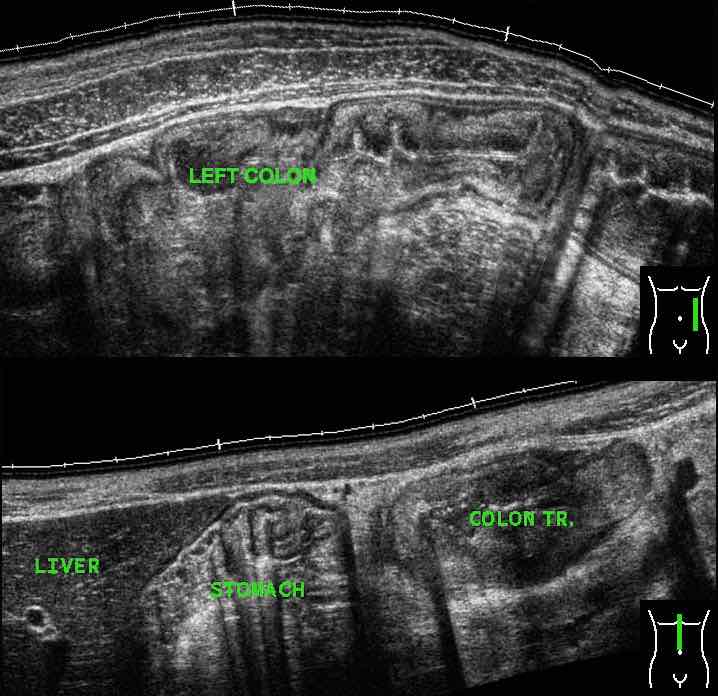

Typical, prominent image of the ileocecal valve in infectious ileocecitis due to (sub)mucosal thickening of both ileum and cecum.

The ileocecal valve is visualized in two planes, perpendicular to each other (note body scheme).

As clinically observed in Campylobacter patients, pain in Campylobacter ileocecitis is often intermittent and crampy in nature.

During these crampy pain attacks (remember “Crampylobacter”), the ileum is slightly intussuscepted into the cecum, sliding back again after the attack.

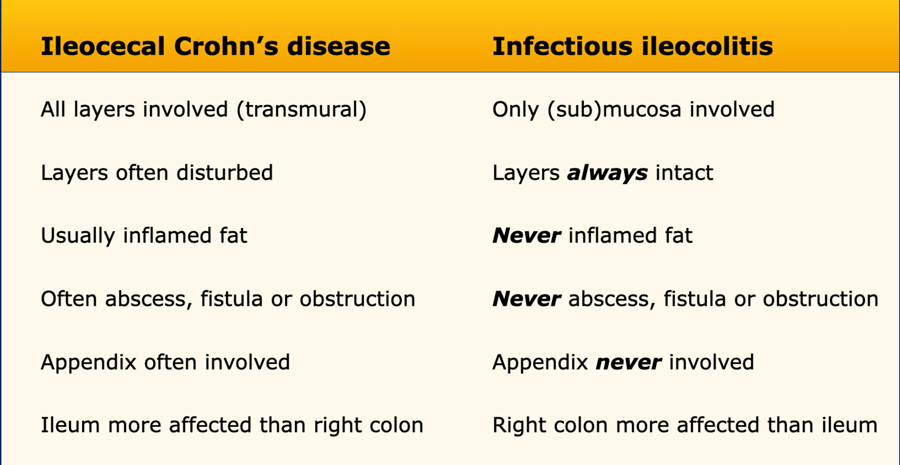

Differentiating Crohn’s disease and infectious ileocolitis is usually easy, as in the latter the layer structure is virtually always intact and there is never inflamed fat, abscess or fistula formation.

Differences between Crohn’s disease and infectious ileocolitis.

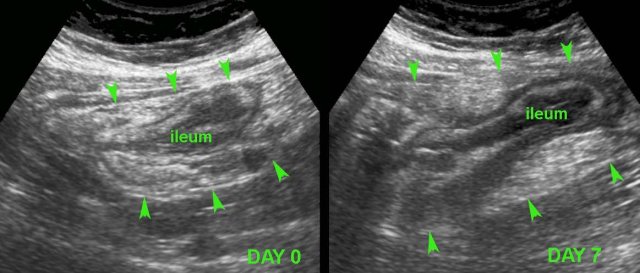

However, differentiation of early Crohn’s disease from infectious ileocolitis, can at times be difficult to impossible.

Follow-up and repeated stool cultures in such cases can solve the problem.

In this young patient, USfindings were compatible with both early Crohn’s ileitis and right-sided infectious ileocolitis.

Repeated US after 7 days waspathognomonic for Crohn’s disease.

Note that both wall thickening and surrounding inflamed fat have markedly increased in volume (arrowheads).

Tuberculous ileitis

In this patient from Indonesia with RLQ pain, the tentative US diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was made.

A chest X-ray however revealed active tuberculosis, so the most likely diagnosis was tuberculous ileitis.

Follow up US after tuberculostatic therapy showed complete resolution of the abnormalities.

Tuberculous ileitis can closely mimic Crohn’s disease, and even show abscesses, fistula formation and fibrotic stenosis.

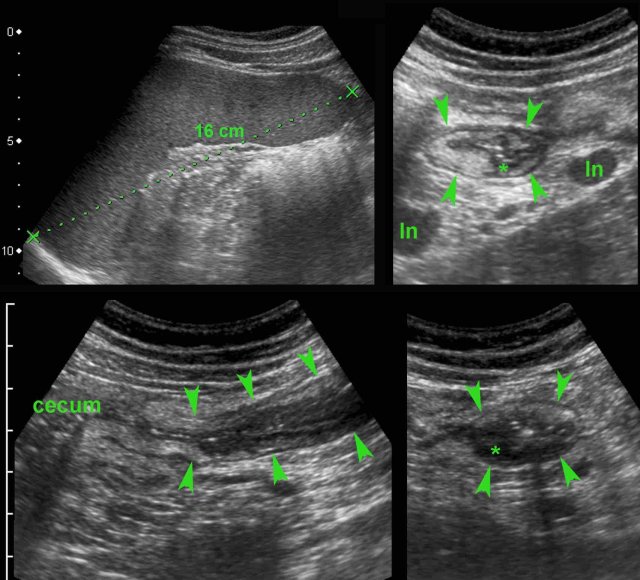

Typhoid ileitis

This Dutch student presented with high fever, constipation and RLQ pain after returning from India.

US showed splenomegaly and wall thickening of the terminal ileum (arrowheads) with evident hypoechoic transmural changes (*).

There was also inflamed fat around the ileum and the mesenteric lymph nodes (ln) were enlarged.

Two days later, blood cultures were positive for Salmonella typhi.

Complete recovery with antibiotics.

S. typhi is the only bacteria that shows this invasive behavior and may very closely mimic the US features of Crohn’s disease.

In endemic areas, ileal perforation is a frequent complication of typhoid fever.

Clostridium colitis may mimic the US features of ulcerative colitis, although the (sub)mucosal wall thickening in Clostridium colitis is usually much more prominent.

The clinical findings may at times be quite confusing and Clostridium colitis may also occur without previous antibiotic therapy.

This young patient developed severe diarrhea, several days after antibiotic therapy for urinary tract infection.

Colonoscopy was suspect and eventually stool cultures were positive for Clostridium difficile.

Ischemic colitis

Ischemic colitis has a predilection for the splenic flexure of the colon since that is the watershed area of superior and inferior mesenteric artery supply.

US findings of sharply demarcated, segmental, hypoechoic wall thickening with transmural features and fat stranding may closely mimic Crohn’s colitis, both on US and CT.

Location, age and atherosclerosis, together with the clinical picture usually give the clue.

Note the abrupt transition of normal and abnormal colonic wall (arrowheads) mimicking skip lesions as in Crohn’s disease.

Clinical findings as well as the atherosclerotic origin of the SMA (arrow) give the clue here.

Bowel malignancy

In patients with segmental bowel wall thickening and loss of the normal US architecture, active Crohn’s disease may mimic malignancy.

Yet, in the majority of the cases, the US appearance of the adenocarcinoma is quite typical.

In this 52-year old man the classic appearance of an adenocarcinoma of the descending colon was found by US.

Longitudinal view shows a short segment ofirregular, asymmetrical, hypoechoicbowel wall thickening with loss of layer structure, especially at the ventral side.

Note that dorsally the wall is relatively intact.In the transverse view, the proximal segmentof colonis normal, more distally prominent hypoechoic wall thickening suggests tumor.

Not only the relatively hypoechoic tumor itself is not compressible, but also the surrounding hyperechoic fat (arrowheads), representing desmoplastic reaction.

Irregular, circumferential wall thickening of the cecum with loss of layer structure and ill-defined borders, separating it from the surrounding inflamed fat.

It was impossible here to differentiate Crohn from malignancy.

On the subsequent CT scan, malignancy was considered more likely.

Colonoscopy revealed cecal carcinoma.

Sometimes, the US image can be quite confusing.

In this patient, the irregular, asymmetrical wall thickening of the cecum with adjacent inflamed fat (*) and encroachment of the appendix (arrow) suggested malignancy with desmoplastic reaction and ingrowth in the base of the appendix.

Concomitant wall thickening of the terminal ileum and especially the transmural changes (arrowhead) in the distal appendix, suggested the correct diagnosis of ileocecal Crohn’s disease with involvement of the appendix.

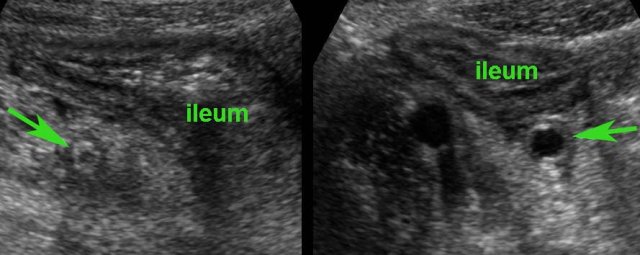

An important pitfall is secondary thickening of the terminal ileum due to advanced appendicitis.

In these two different patients (who both turned out to have appendicitis), prominent wall thickening of the ileum initially raised the suspicion of Crohn’s disease or right-sided infectious ileocolitis.

Further US searching brought to light that this was reactive thickening due to an underlying inflamed appendix (arrow).

When the appendix is not visualized in such cases, secondary wall thickening of the ileum may be misinterpreted and may lead to serious delay of surgery.

In doubt, CT can be very helpful.

Role of US in Crohn’s disease

Primary detection

The main role of US in Crohn’s disease is primary detection in patients who are submitted for US with an unclear diagnosis. These patients have either very atypical chronic symptoms of pain and/or diarrhoea or they present with appendicitis-like symptoms or small bowel obstruction.

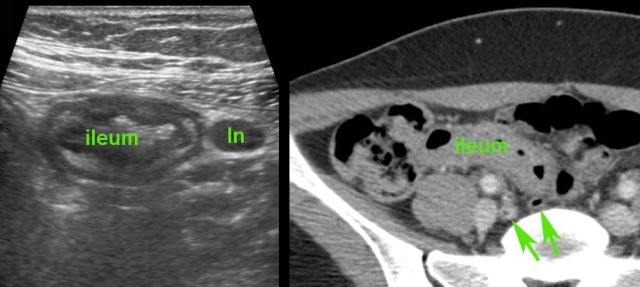

This 28-year old man with a blank medical history, presented with RLQ pain since 24 hours, suspect for appendicitis.

US and subsequent CT showed a completely unexpected Crohn’s ileitis with enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, and a normal appendix.

Not infrequently, Crohn’s disease may even be a coincidental finding in a patient, who at that time, has no abdominal symptoms at all.

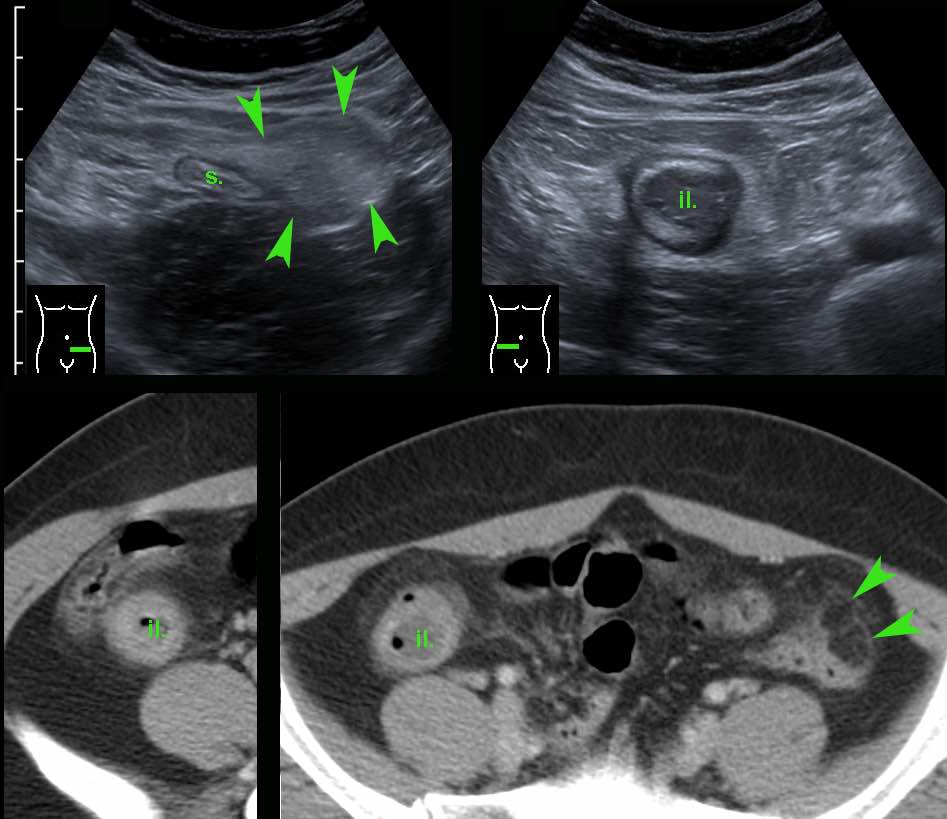

This 32-year old lady presented with severe LLQ pain and a CRP of 20.

In the LLQ, US revealed a locally painful mass of inflamed fat next to the sigmoid (s.), suspect for epiploic appendagitis.

During screening (“mowing-the-lawn”) in the RLQ an abnormal terminal ileum (il.) was found with all US features of Crohn’s disease.

The patient denied any present or previous symptoms other than the actual pain in her LLQ, which subsequently subsided within a week.

CT confirmed left-sided epiploic appendagitis (arrowheads) and Crohn’s ileitis.

In the following years, this patient did actually develop active, albeit rather mild, symptomatic Crohn’s disease, without abscess or fistula formation.

Monitoring disease activity during medication

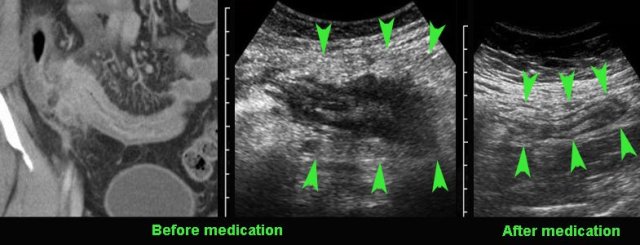

US can also be used for monitoring disease activity during medical therapy for Crohn’s disease, particularly in circumscribed Crohn's disease of the terminal ileum or colon and in well-circumscribed and reproducible lesions.

Compare the severely affected terminal ileum in this young patient with the US image after 8 months of medical therapy.

Note that both wall thickening and the mass of acutely inflamed fat around the ileum did decrease (arrowheads).

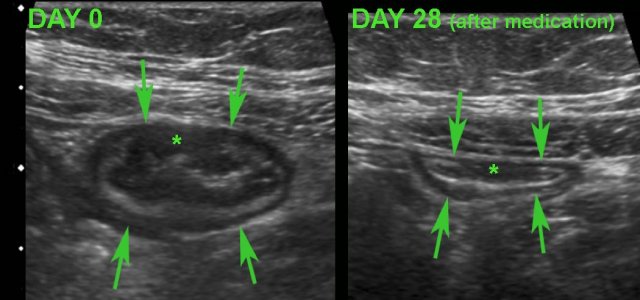

Monitoring disease activity in response to medical therapy at the level of the terminal ileum.

There is convincing decrease in wall thickening after 4 weeks of medication.

Note subtle residual hypoechoic, transmural changes (*) still visible in the near wall after therapy.

US in abscess drainage

Although MRI and CT are essential in delineating Crohn’s abscesses and in treatment planning, US can be helpful in guiding abscess drainage.

In this obese patient, US with gtraded compression was useful to safely guide the needle to this deeply located abscess.

After insertion of a guide-wire, an 8-Fr pigtail-catheter could easily be placed under fluoroscopic control.

Crohn colitis vs ulcerative colitis

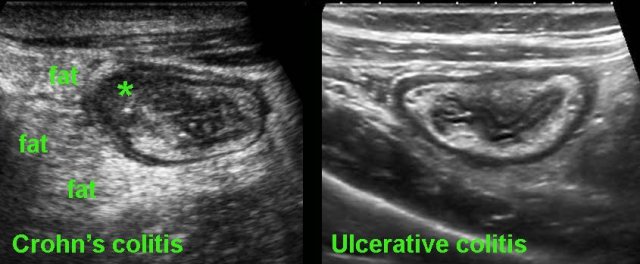

Finally, US may play a role in the differentiation of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis.

On clinical grounds and even with the help of endoscopy and biopsies, it can at times be difficult to differentiate Crohn’s colitis from ulcerative colitis.

In these cases, US can be of help: the demonstration of hypoechoic, transmural inflammation and the presence of non-compressible inflamed fat strongly favor Crohn’s disease.

Pitfall

In severe ulcerative colitis, there may be increased echogenicity of the surrounding fat (*), as here in this young pregnant lady.

This fat is rather well-compressible, and should be considered as edema associated with secondary hyperemia rather than as a sign of true transmural inflammation.

Note marked wall thickening of the transverse colon (arrowheads) in the panoramic view.

We thank Lars Perk, gastroenterologist, for his critical evaluation of the manuscript.

-crohn-coll-1610801212.jpg/eb84a8be417a85338f17d25badb44b38/3-selim-030987-v1-(0244179)-crohn-coll-1610801212.jpg)

-crohn-coll.jpg)

cro-colitis.jpg)

crohn-vag-us-fistel-coll.jpg)

crohn-ileus-musc-coll.jpg)

-oude-crohn-ascend-coll-kopie.jpg)

-crohn-app-coll.jpg/186ebf7cdc7013eb6f2ac95ad61dd698/27-berkel-131110-m2-(4030686)-crohn-app-coll.jpg)

-isch-colitis-coll2.jpg)