Non-traumatic changes

Mini Pathria and Jennifer Bradshaw

Department of Radiology of the University of California School of Medicine, San Diego, USA and the Medical Centre Alkmaar, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

This article is based on a presentation given by Mini Pathria and was adapted for the Radiology Assistant by Jennifer Bradshaw.

In part I we discussed the MR features of various muscle injuries.

In part II we will discuss non-traumatic muscle changes.

Introduction

When assessing muscle pathology try to decide which one of the four basic patterns of abnormality is present:

-

Muscle edema, i.e. increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images in muscle with otherwise normal anatomic architecture:

- Injury

- Myositis: infectious myositis, necrotising fasciitis, auto-immune myositis (polymyositis, dermatomyositis)

- Imflammatory myopathy: Graves disease

- Radiation therapy

-

Muscle atrophy, i.e. too much fat:

- Disuse

- Chronic denervation due to nerve entrapment, poliomyelitis

- Muscular dystrophy: Duchenne

-

Mass within muscle:

- Soft tissue tumor

- Hematoma

- Abscess

-

Accessory muscle, i.e. abnormal anatomy with normal signal

Some of these conditions, such as polymyositis, require biopsy for appropriate therapy to be initiated.

In other conditions, such as myositis ossificans, biopsy should be avoided because it may lead to an incorrect diagnosis of a neoplasm and thus to inappropriate therapy.

Clues to the correct diagnosis and whether biopsy is necessary are often present on the MR images, especially when they are correlated with clinical features and the findings from other imaging modalities (1).

The patient on the left had slipped on the ice in the hospital parking lot and torn the hamstrings.

The hamstring tear was associated with sciatic neuritis, when the sciatic nerve became irritated by the hematoma.

Muscle Edema

Muscle edema is the most common MR-pattern.

It is hard to make a specific diagnosis based on the MR-findings alone.

Be sure to get the right history because it usually provides the clue.

The most common cause of muscle edema is trauma, which was discussed in Muscle MR imaging - Part I.

Inflammatory myopathy

Inflammatory myopathy is a term that defines a group of muscle diseases involving inflammation of skeletal muscle and often the adjacent fascia, with elevated CPK.

They are thought to be autoimmune disorders.

When using the term inflammatory myopathy, one is actually considering three separate disease entities, namely dermatomyositis (DM), polymyositis (PM), and inclusion body myositis (IBM).

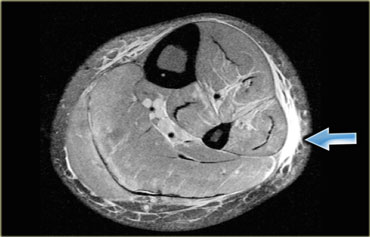

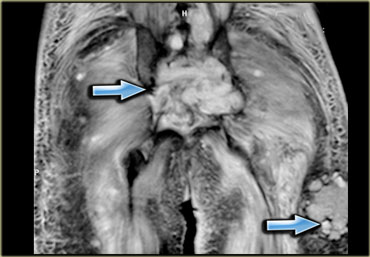

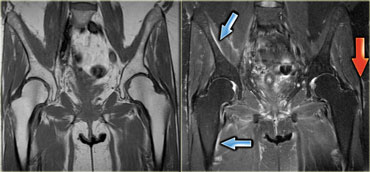

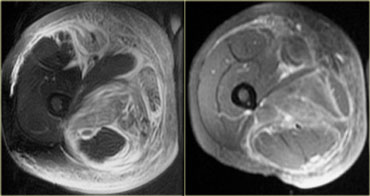

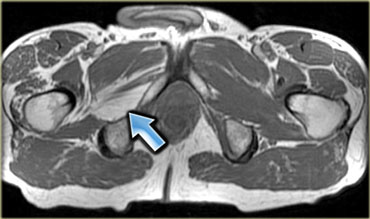

On the left an example of inflammatory myopathy.

Note increased signal of all the muscles, in all the compartments.

This is edema.

There is also some edema of the subcutaneous tissues.

It is very unusual for a trauma, for example, to present with edema in all compartments.

There are no fluid collections within the muscles, but notice the perifascial fluid collections.

On the left a patient with myositis.

Again we see that multiple compartments are affected, there is a vast amount of edema, skin involvement and perifascial fluid.

It is non-specific but myositis could be suggested. Inflammatory myositis is generally bilaterally symmetrical.

MR features of myositis include normal architecture on T1-weighted images, feathery edema with enhancement, skin reticulation and abnormalities NOT limited to specific compartmental or neural anatomy.

Polymyositis

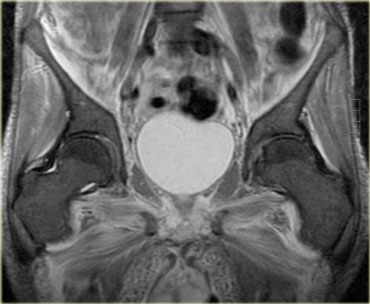

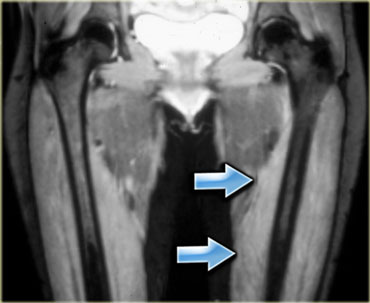

On the left a patient with polymyositis (PM), one of the inflammatory myopathies.

The large proximal muscles are involved, generally in a symmetric pattern.

Generally speaking, not all muscles are involved, so MR can help locate the best area for biopsy.

Sometimes whole body MR is used for diagnosis and follow-up of polymyositis after steroid therapy has been initiated.

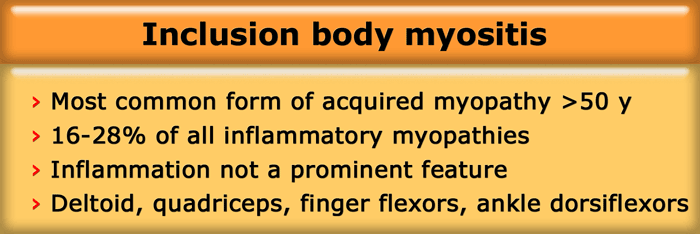

Inclusion body myositis

Induction body myositis, one of the inflammatory myopathies, is a more recently recognized form of myositis of unknown cause.

It is the most common acquired myopathy in patients > 50 years and makes up about a quarter (16-28%) of all inflammatory myopathies, although inflammation is not a prominent feature in this disease.

It is an indolent disease and there are no skin changes.

The muscles that tend to be involved are the deltoid, quadriceps (see next example), finger flexors and ankle dorsiflexors.

Patients present with muscle weakness, the disease owes its name to the histological finding of vacuoles and filamentous inclusions.

Although the findings are non-specific, it is worth considering this diagnosis in a older patient with abnormalities of the above mentioned muscles.

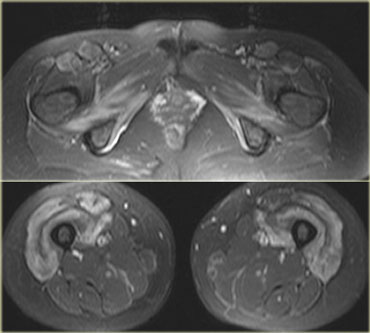

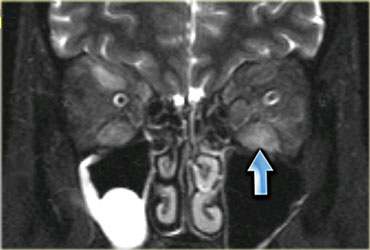

On the left a patient with inclusion body myositis.

Notice the symmetrical involvement of the quadriceps and the lack of edema in the surrounding tissues.

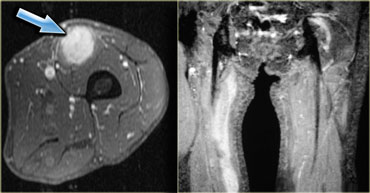

Myositis in collagen vascular disease

Patients with underlying collagen vascular diseases can develop myositis,

such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), mixed connective tissue disease and Sjogren syndrome.

For example, as in this patient with SLE, it can be very focal (coronal image, right leg, adductor loge) or nodular.

A type of nodular myositis is focal proliferative myositis, it is the least common form.

This can be seen in association not only with collagen vascular diseases but also lymphoma.

The lesion caused by myositis is sometimes indistinguishable from lymphoma itself, and biopsy is necessary to make the diagnosis.

On the left another patient with focal nodular myositis which looks like any other mass on T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and post contrast.

With a history of lymphoma you could suggest focal nodular myositis, but there is nothing definitive about the images.

The relationship of myositis to underlying malignancy remains controversial, and the frequency of this association is not well established.

2 types of cancer show a relationship with myositis: ovarian cancer and Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

(shown on the left a patient with, strangely enough, metastatic thyroid cancer).

Myositis can precede malignancy (as in a paraneoplastic syndrome), which is not to say that routine screening for malignancy

is called for in patients presenting with myositis.

Radiation myositis

Myositis due to radiation can be seen many years after the therapy.

It seems to be a vascular problem which doesn't disappear after cessation of the therapy.

The history is usually the clue, but also you may see a band like appearance where the radiation changes in the muscles stop, corresponding with the radiation field.

Graves disease

On the left a well-known example of inflammatory myopathy which has an endocrine etiology: Graves disease, otherwise known as thyroid eye disease.

The inflammation of the eye muscles and orbital fat with subsequent volume increase leads to proptosis.

Same patient, coronal T2-weighted image.

Drug induced myositis

Several drugs can induce myositis and in the author's practice the most frequent culprit seems to be a lipid-lowering statin.

In a significant number of patients statins induce muscle pain and myositis, the dosage then needs to be decreased or the drug needs to be discontinued.

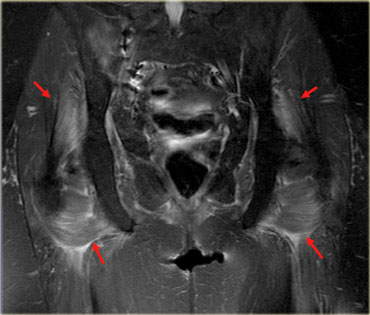

On the left an example, note the inflammatory changes in the large muscles around the buttocks.

After discontinuation of the drug, the muscle pain will disappear in about 2 weeks, the MRI however will still show abnormalities until roughly a month later.

The best time to do a follow-up MR is about 6 weeks after stopping the drug.

This was an older patient with elevated cholesterol who was put on Lipitor.

The patient developed muscle aches and pains, CPK was mildly elevated.

The changes are rather subtle, we see perifascial fluid collections, around the edges of the muscle (the epimysium).

Also there are minimal skin changes.

HIV myositis

Antiretroviral drugs (used in HIV positive patients) can also cause myositis because they interfere with the mitochondrial repair mechanism.

The abnormalities are very similar to those in myositis induced by lipid-lowering statins.

Again, the patients present with weakness and pain, the changes are centrally located in the larger muscles.

The differential in HIV positive patients is relatively long (autoimmune, HIV wasting syndrome with type II muscle fiber atrophy,

denervation and infection).

It is obviously important to be able to rule out infection in these patients.

One way to differentiate between the two is to look for symmetry. Zidovudine (AZT) myopathy, or HIV myositis, is symmetrical.

Infection is usually unilateral or at least asymmetrical.

T1-weighted image with fatsat post contrast Fluid collections within the enhancing muscle in a patient with pyomyositis

T1-weighted image with fatsat post contrast Fluid collections within the enhancing muscle in a patient with pyomyositis

Myositis due to infection

Muscle infection or myositis without abscess or necrosis may produce edema as the sole abnormality on MR images.

The MR images and clinical history may suggest the presence of such an infection.

Bacterial myositis frequently progresses to abscess formation and thus often has a masslike appearance on MR images.

Viral infection does not progress to abscess formation.

Muscle infection can be due to:

- Hematogenous: pyomyositis, parasitic

- Local spread: cellulitis, osteomyelitis

- Autoimmune response: Lyme disease, Influenza

Important groups at risk for muscle infection are diabetics, immuno-compromised patients, patients with a penetrating wound (including ulcers that cause infection to spread deep or skin infections).

The hallmark of muscle infection is fluid collections present inside the muscle (figure).

Pyomyositis

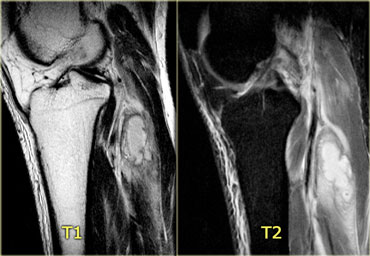

On the left T2-weighted, T2FS, and post contrast sagittal images of the knee.

On the T2-weighted image we see a posterior mass with inflammatory changes in the surrounding muscles.

The T2-weighted image with fatsat shows an ill-defined fluid collection and the inflammatory changes in the muscle are clearer.

So far this is a non-specific finding.

It could be a tumor but tumors tend not to have so much inflammatory change around them.

Lack of central enhancement combined with surrounding inflammatory changes and a suggestive history will help to make the diagnosis of pyomyositis.

Same patient, T1-weighted image post Gadolineum with fatsat.

Pyomyositis (2)

On the left another example of pyomyositis, much more extensive, in a patient with AIDS who had a loculated abscess.

Note the thick enhancing walls.

On the left another case of pyomyositis.

Note the asymmetry with enlargement of the left extremity.

There is subcutaneous, fascial, and muscular inflammation.

Generally speaking muscle infection is a clinical diagnosis, but MR can help determine the depth and extent of the disease.

MR also is helpful to locate fluid collections or abscess formation, which can then be aspirated for culture.

Pyomyositis (3)

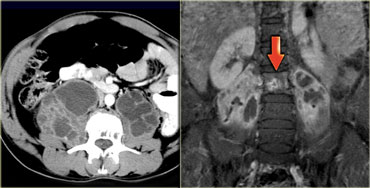

On the left bilateral psoas abscesses as a complication of osteomyelitis of the spine in a patient with TB.

Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare infection of the deeper layers of skin and subcutaneous tissues, easily spreading across the fascial plane within the subcutaneous tissue.

Group A streptococcus is the most frequent pathogen found in necrotizing fasciitis.

These bacteria are sometimes called 'flesh-eating bacteria', which is a misnomer as the bacteria do not actually eat the tissue.

They cause the destruction of skin and muscle by releasing toxins, which include streptococcal pyogenic exotoxins.

Sarcoidosis

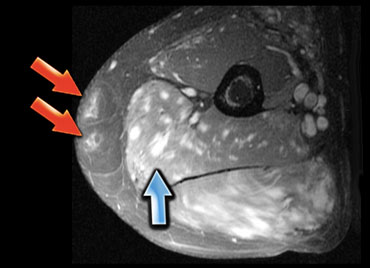

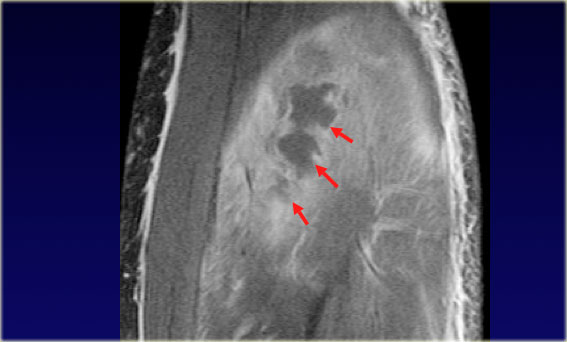

On the left an example of another inflammatory disease: Sarcoidosis.

Sarcoid is confusing on MR, because you will see changes in the skin and a peculiar nodular enhancement pattern in the muscle.

1-2% of patients with active sarcoid will have muscle involvement and there are always skin changes on the overlying skin.

The enhancement pattern is also referred to as the 'Stars and Stripes' pattern, mostly because of the stripes on the long axis of the muscle.

Here a patient with sarcoidosis of the skin.

A MRI was performed because of a small mass within the muscle of the lower leg.

Scroll through the images and notice how strange these sarcoid lesions are orientated within the muscle.

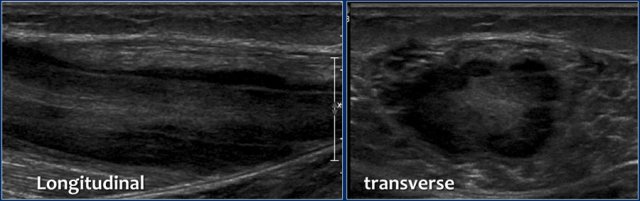

Here another patient.

Notice the longitudinal orientation of the lesion along the muscle fibers on the longitudinal image.

On the MR the lesions are almost identical compared to the other patient.

Notice the orientation on these coronal images.

There is some edema, but almost no mass effect.

On these axial T2W-images with fatsat notice again the strange appearance of these lesions.

Muscle Atrophy

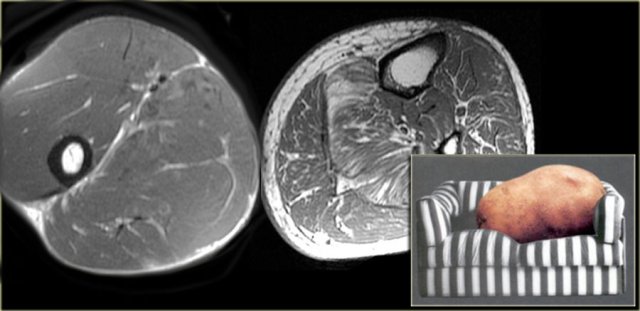

The fat present in a muscle will be either intramuscular or intermuscular.

There obviously is a wide range of amount of fat present.

Far left an example of an olympic gymnast with 6% body fat.

Next to it an example of most of us mortals, the so called couch potato, with much more intra- and inter-muscular fat.

Atrophy patterns

The image on the far left demonstrates fatty infiltration of muscle in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is also known as hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy or peroneal muscular atrophy.

It affects both motor and sensory peripheral nerves.

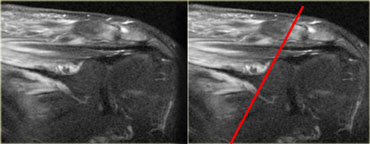

The image next to it demonstrates atrophy of the supraspinatus muscle.

The supraspinatus muscle is small and there is peritendinous atrophy.

This is the pattern that you will see when the tendon is torn and there is disuse.

Denervation and Peripheral nerve entrapment

In the acute phase of denervation, the MR is normal.

In the early subacute phase after one week, there will be uniform muscle edema and paradoxical hypertrophy (the muscle looks swollen).

In the late subacute phase after 3 weeks, there will be mixed edema and atrophy.

The chronic phase is characterized by only atrophy.

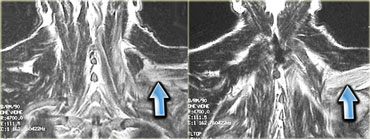

On the left a patient with cervical root avulsion.

The para-spinal musculature shows a mixture of edema and atrophy, 3 weeks post-trauma.

On the left a patient with peroneal nerve entrapment by a ganglion, leading to atrophy of the peroneus longus, peroneus brevis and the anterior compartment.

Note the increased signal intensity of the anterior muscles, due to edema, meaning early atrophy.

On the left an example of atrophy in a patient with a resection arthroplasty of the right hip (Girdlestone procedure).

There is atrophy of the thigh musculature and gluteal muscles due to disuse.

There is a decrease in size of the muscles and there is fatty replacement in a peritendinous pattern.

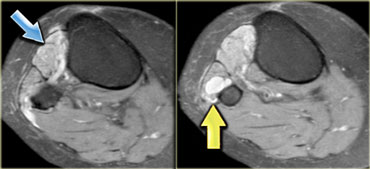

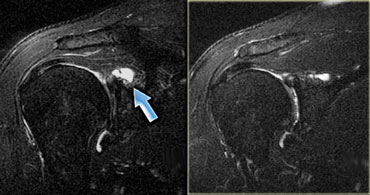

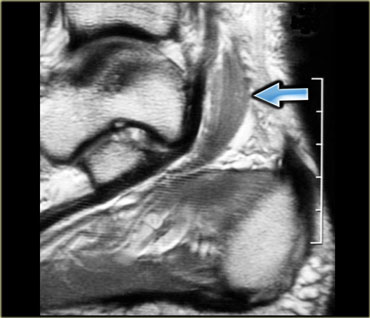

On the left a patient with a ganglion (blue arrow) in the shoulder.

Stop and think for a moment about what causes ganglions in the shoulder.

There is a subtle increase in signal in the infraspinatus muscle (yellow arrow), due to edema.

Remember that the early subacute stage of denervation presents with edema.

The nerve is being impinged by the ganglion.

This patient had a labral tear (not pictured), which can lead to ganglion formation.

It is important to make this diagnosis while the muscle is not yet atrophic.

If the ganglion is aspirated or removed on time, the nerve function will be restored before the muscle becomes atrophic.

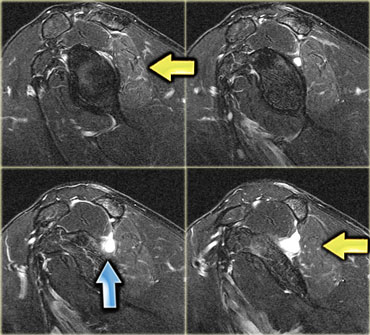

On the left a different patient with a paralabral ganglion (not pictured).

There is atrophy of both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscle.

There is volume loss and edema, without any focal fluid colllections.

On the left a case in which the obturator nerve was clipped at surgery.

This is the chronic phase where there is volume loss and fatty replacement of the muscle.

On the left another patient with a tear of the posterior labrum and a paralabral cyst.

Study the images and try to determine if there is any atrophy.

Then continue with the T1-weighted image.

This case illustrates how important it is to include a T1-weighted image to your exam!

If you were to have only the T2-weighted image with fat sat, you would miss the atrophy of the supraspinatus muscle, which has been entirely replaced by fat.

The chronic phase of denervation is characterized by only atrophy.

On the left images of a patient with an Erb's palsy.

On the left images of a patient with chronic denervation due to polio.

On the left a patient with edema of both the deltoid muscle and the supraspinatus.

This is an important observation since these muscles are innervated by different nerves.

The deltoid muscle is innervated by the axillary nerve and supraspinatus muscle by the suprascapular nerve.

This means that the lesion is more proximal.

This patient had Parsonage-Turner Syndrome, also known as brachial neuritis.

This is an inflammatory disorder characterized by severe pain, followed by weakness due to denervation.

Note also edema of the infraspinatus muscle.

Muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophy is a less common cause of atrophy.

It is diagnosed clinically usually in children, with patients experiencing symmetrical muscle weakness, pseudohypertrophy of the calves and difficulty in standing up.

The muscle initially is edematous and then rapidly becomes atrophic.

There are many types of muscular dystrophy.

The most common type is Duchenne.

On the left an example of adult onset muscular dystrophy.

There is subtle high signal intensity of the quadriceps muscle bilaterally due to edema, with a feathery appearance.

Most of the adductor muscle is normal.

Note the lack of skin edema.

This is an important finding to be able to differentiate from inflammatory myositis, in which the skin is also edematous.

The imaging findings correspond to the acute stage of muscular dystrophy.

In a chronic setting, the muscle will be atrophied with fatty replacement.

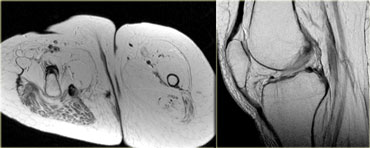

On the left T1- and T2-weighted images of the thigh muscles.

Notice that there is an obvious difference between the signal intensities of the quadriceps muscle and the posterior muscles.

On the T1-weighted image only the posterior muscles contain normal fat.

On the T2-weighted image there is edema of the quadriceps, which is a sign of early muscular dystrophy.

Although the exact diagnosis cannot be made by MR, it can be helpful in suggesting a location for biopsy to determine the type of muscle degenerative disease.

On the left an example of chronic muscular dystrophy.

The muscle has been entirely replaced by fat.

When the muscle loses its nerve supply it becomes atrophic.

Dysfunction at any level of the motor unit can lead to denervation with muscle atrophy as a result.

Accessory muscles

Accessory muscles may present as an asymptomatic painless mass or with symptoms of nerve entrapment or vascular entrapment.

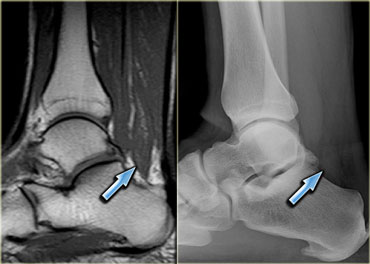

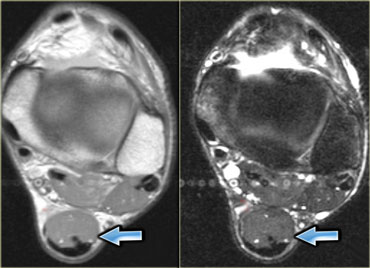

On the left an example of an accessory soleus, on the medial side of the ankle, which caused compression of the tibial nerve (i.e. tarsal tunnel syndrome).

In order to diagnose this entity, you must be really familiar with the anatomy of the area being studied.

Patients with accessory muscles will usually present with a painless mass, which will be marked by the lab technician.

Initially, the MR appears normal.

However, be aware that there are 3 questions that you must consider in these cases:

- Is there a subcutaneous lipoma (very easy to miss when imaging)

- Is there fibrous tissue or fibromatosis on the fascia (also, very easy to miss because it is dark tissue on fascia)

- Is there an accessory muscle

On the left a wrist examination showing an accessory forearm flexor muscle.

On the left an example of an accessory muscle at the dorsum of the wrist (T1- and T2-weighted).

Under the marker is a well-defined mass, iso-intense to normal muscle.

It is a muscle at mid-carpal level, with normal signal.

Normally, at this level, there is no muscle on the extensor side of the wrist, just tendon.

This is an accessory extensor digitorum manus brevis.

A recent article in Radiographics lists the accessory muscles in the human body

(Sookur PA et al. Accessory Muscles: Anatomy, Symptoms, and Radiologic Evaluation. Radiographics 2008;28:481-499).

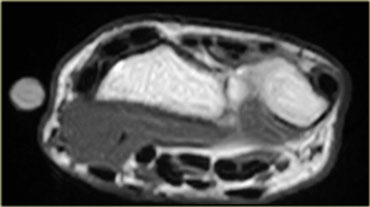

On the left an example of a common accessory muscle: the accessory soleus.

Normally the soleus muscle inserts almost entirely onto the achilles tendon with a very small soleal tendon passing anteriorly to the achilles tendon.

In about 1-2% of the population however, the soleus comes down and inserts directly onto the calcaneus.

This will present as a palpable mass and is usually, but not always, bilateral.

On the left a low lying soleus muscle, but it did not have a separate tendinous insertion on the calcaneus.

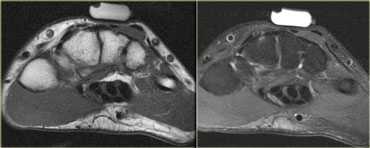

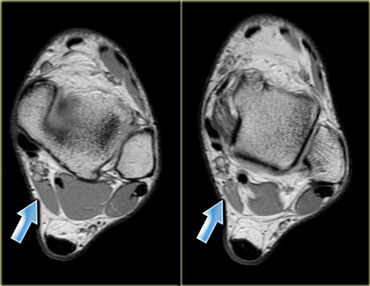

On the left another example of an accessory muscle which lies medial to the flexor hallucis longus (middle) and peroneus brevis (lateral).

This is a common area for accessory muscles, and there are a lot of different muscles that can be found here (to differentiate you need to determine where the tendon inserts).

The reason that this is presented for imaging is because it compresses the adjacent neurovascular bundle leading to atrophy of the muscles of the foot or tarsal tunnel syndrome with tingling of the sole of their foot or weakness.

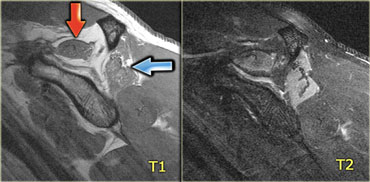

Accessory anconeus epitrochlearis muscle (red arrow)Ulnar nerve with high signal indicating ulnar neuritis (blue arrow)

Accessory anconeus epitrochlearis muscle (red arrow)Ulnar nerve with high signal indicating ulnar neuritis (blue arrow)

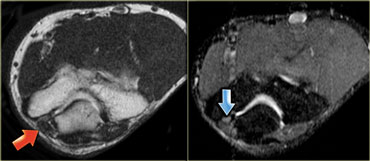

On the left an elbow, the medial side is on the left.

Note that there is a muscle directly behind the ulnar nerve, which in a normal situation whould not be present.

This is an accessory anconeus epitrochlearis, found in 10% of the population.

It is a common cause of ulnar neuritis, due to compression, with pain and tingling of the ulnar side of the hand, and sometimes atrophy of the hypothenar and thenar musculature.

Always look carefully at the nerve when you have encountered this muscle.